Choice Overload – How Having Too Many Options Can Shut Down Your Brain

Being able to choose what to pursue in life – or what kind of shampoo to use – is in fact how we define freedom. But is there such a thing as too much choice? Too many options? Enter, choice overload.

Article content:

Definition of Choice overload

Choice overload or overchoice is a cognitive impairment that occurs during a decision-making process when we are presented with too many options we cannot easily choose between. Our ability to make a good decision is reduced by the overload of choices, as is our satisfaction with the final decision.

Choice Overload

Choice overload is a result of too many choices being available. It can result in decision fatigue, sticking to the default option, or even avoiding making a decision altogether.

Choice overload is most likely to happen, when deciding in an area we are not knowledgeable enough about. Its effects diminish the more familiar we are with the subject (professional bakers will not have a problem choosing a type of flour) as well as with how well defined our opinion on the subject is (although you might not be an expert on crisps, you are familiar enough not to be paralysed by the multitude of options in the store).

What are the symptoms?

Do you remember that time you went to a wine shop to grab a special bottle for date night with your significant other? You walked in, wandered around among all the Sauvignons and Pinots with different countries of origin, vintages, and flavor profiles … just to leave with the same bottle of Riesling you always go for.

How did it happen?

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Well, you went in, and there was this beautiful bottle of Pinot Gris, just perfect. But wait! What about that Montepulciano over there? Your spouse loves the drier stuff. Oh, and there was an interesting fortified Australian Shiraz that had won some kind of award.

Ok, that one might be great, let’s go with it …. Or should you? What if the bottle next to it is much better? And what does “fortified” even mean? You just can’t decide!

And then your mind snapped – you put the fancy wine back, grabbed the tried and tested bottle and left.

Watch this TED Talk by Sheena S. Iyengar, author of one of the most famous studies on the subject of choice overload, showing several interesting examples of choice overload – as well as several ways to mitigate it.

Source: YouTube

Why does it affect us?

In more than 600 studies throughout the years (such as “How to Make Nothing Out of Something: Analyses of the Impact of Study Sampling and Statistical Interpretation in Misleading Meta-Analytic Conclusions” by Michael R. Cunningham and Roy F. Baumeister, a more recent meta-analysis), scientists have proven that making decisions drains our willpower in a process called “ego depletion”.

Willpower is a resource similar to your physical energy, but for decision-making. While exercise or physical work fatigues muscles in your body, every decision – even small ones – taxes our brain and drains our willpower for decisions down the line.

Willpower is a resource similar to your physical energy, but for decision-making.

Exercise is actually a perfect analogy here.

When you start your workout, your muscles are fresh and can achieve a certain level of performance. If you push hard enough, your energy level comes down and your muscles get fatigued. With the depleting resources of glucose and minerals, your ability and your willingness to continue decrease until you just stop and take a rest. Or push yourself too hard and irresponsibly injure yourself.

Your brain is just the same with willpower.

At first, your ability to make decisions and stick with them is in peak form. But every decision strains your mind and numbs you to each subsequent decision you have to make. In order to cope and not get overloaded, the brain starts to simplify everything, throwing out the non-essential bits to reduce the complexity.

As your “ego” depletes, your brain trips a safety circuit.

Just think about your experience of voting in local elections.

At first, you carefully weigh every pro and con of every candidate. As information about the wrongdoings of one or the other pour in from the media, you start to lose your grip. You leave more complex reasoning behind and settle for simple answers on seemingly more clearcut questions, like immigration or taxes. And in the end, after months of campaigning, you just want it all to be over with. You pick the one who seems the nicest of the bunch – the one that seems to care about the same things you care about but doesn’t require any more of your precious thinking resources.

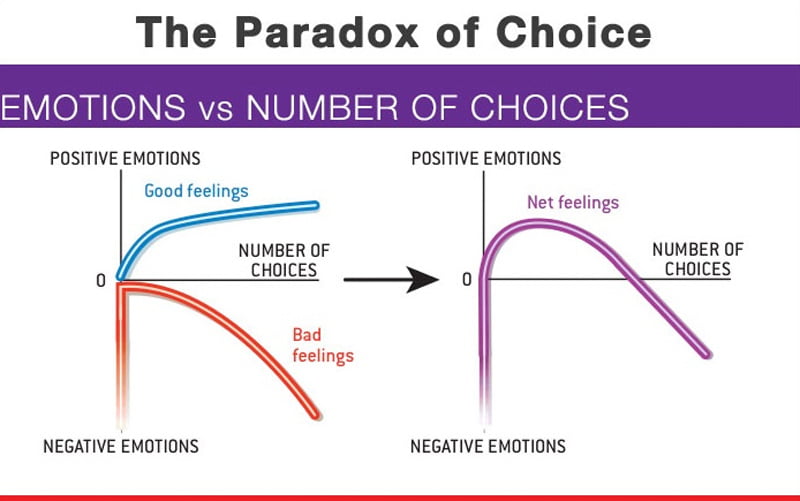

The amount of willpower drained also depends on the type of your reaction to decision-making.

Maximizers yearn for the best possible decision, and really weigh all the options. This is obviously a drain on their willpower – and they tend to be less satisfied with their decisions.

And then there are Satisficers who are satisfied with a “good enough” decision. If you are a more laid-back type of person, or just don’t care about the thing enough to give your all to the decision-making process, your ego won’t be depleted nearly as much. Satisficers tend to be happier about their choices and might not feel the effects of the choice overload altogether.

Although there are many studies confirming the theory of ego depletion, some studies in recent years have disputed the concept. Some experiments have shown that willpower depletion only affects people who believe in willpower being a limited resource – further research needs to be done before a definite conclusion can be made.

Choice overload experiments

The jam experiment

When it comes to experimental evidence, choice overload is kind of a hot subject.

It has been more than 20 years since Sheena S. Iyengar and Mark R. Lepper from Columbia University published their study “When Choice is Demotivating: Can One Desire Too Much of a Good Thing?”, in which they presented a set of 3 experiments (including the famous “jam experiment”) pointing to the existence of choice overload.

In the first and most famous of the three, Iyengar and Lepper set up a jam tasting stall in an upscale grocery store in Menlo Park, California. Over the course of a few days, they offered tastings of several jams to customers. They were trying to study the effect on shopping behavior of having multiple options. So together with the samples, they also handed over a voucher for a small discount and tracked the usage of the coupons in the days that followed.

During the first day, they offered samples of 24 jams at the stall, then the next day reduced the offer to just 6 samples.

About 30% of people who tried one of 6 flavors bought the jam afterwards, in the case of the more extensive options it was 10x less – only 3% of people went on to make a purchase.

The wider selection attracted more customers at first – 60% of passers-by stopped to have a look at the selection of 24 flavors, as opposed to just 40% when only 6 flavors were on display. But that is where the positives for more options ended.

Regardless of the number of options on offer, people tried out 1-2 jams on average (1.5 samples for the 24-option set-up, and 1.38 for the 6-option set-up). And when it came to the effect of tasting on sales of the preserves, the fewer-option selection steamrollered the larger selection. While about 30% of people who tried one of 6 flavors bought the jam afterwards, in the case of the more extensive options it was a whopping 10x less – only 3% of people went on to make a purchase.

Source: Noah Rickhun

So, is it settled? Are fewer options always better?

Not so fast! The limitations of the jam experiment led to 2 more experiments to try to cut down on possible errors in the first one.

The essay experiment

In the second experiment, they observed the effect of choice overload on motivation.

This experiment was held directly on the university grounds. 2 groups of students from the social psychology class were presented with an opportunity to write an essay on a movie, which could earn them 2 extra credits. The first group got to pick from 6 predefined topics, while the other group had 30 topics to choose from.

Can you guess which group of students submitted more assignments?

If you guessed the group with the least options, you were right! 75% of students wrote and submitted their papers if they had only 6 topics to choose from – while only 60% of the group with 30 topics delivered their work. That is a staggering difference!

The students’ work was also graded and assessed qualitatively.

Here again, the group of students with fewer options had the upper hand, although by a smaller margin.

So in the end, less time spent choosing a topic led to more and higher quality essays than when given a multitude of options.

The desirability experiment

In the last of the 3 experiments, Iyengar and Lepper focused on the subject of desirability.

Do we like the decision-making process more after we are shown a multitude of options?

The final experiment presented 2 groups of people with a selection of 6 or 30 chocolates from which they had to choose ones to try out. Then they were presented with a selection of chocolates to taste – one group consisting of the chocolates they had chosen, and the other a predefined set of chocolates.

After tasting, they were offered compensation for their time – either a 5-dollar bill, or a box of chocolates worth the same amount. How did the range of options and ability to choose from them affect their perception of the whole process?

Participants with too many options found the decision-making process difficult and frustrating – but interestingly, also enjoyable. On the other hand, they were less satisfied with their final choice.

What about the limited choice group?

People who got to choose from only 6 chocolates were not only happier with their final choice, but 48% of them preferred to take the chocolates rather than money at the end. The decision-making process was also easier and less frustrating – although not necessarily more enjoyable.

And just for good measure, the group who did not get to choose in the tasting ranked the lowest in satisfaction.

History of choice overload

The term choice overload was first coined by futurologist and entrepreneur Alvin Toffler, in his book Future shock, published in 1970. Toffler analysed the effects of “too much change in a too short timeframe” on society and the human psyche – and for the first-time, dealt with the theme of “freedom of choice” becoming the opposite, unfreedom, as a direct result of having too many choices.

However, the effect of too many choices on the decision-making process had been an area of study for some years prior. As early as 1956, Miller had concluded in his study of memory that adult customers’ brains can compare between 5 and 9 alternatives. Dealing with more than that while shopping requires us to make a system to compare the alternatives.

Throughout the 70’s and 80’s, a plethora of studies such as “Consumer Perceptions: Overchoice in the Market Place” (1976), seemingly confirmed the existence of overchoice. However, the story was not to be so simple – and by the turn of the century, with hundreds of studies hinting at the existence of this phenomenon, evidence against the existence of choice overload started to stack up.

After Iyengar and Leper’s study, the scientific community delved deeper into the problem of overchoice, but often failed to find enough supporting evidence. Attempts at replicating the effects of the jam study have sometimes failed to yield the expected results, and some meta-studies have suggested that the effect was negligible to non-existent and more likely a result of decades-long confirmation bias.

Overchoice remains to this day a popular field of study for psychologists and behavioral economists alike.

Overchoice remains to this day a popular field of study for psychologists and behavioral economists alike. But while decades of findings are used by professionals in the field of business or behavioral economics with remarkable success, conclusive evidence remains to be discovered.

In the end, if it might help you – or your customers – to be less confused and better at making decisions, why not try to fight choice overload?

How to avoid the effects of choice overload

There are multiple effects of choice overload – and we will go through some of them to give you a recipe on how to deal with them when shopping.

Replenish your willpower

The first effect of having too many decisions to make is the “ego depletion” we talked about earlier in this article.

How can you combat fleeting willpower? The answer is surprisingly physical – have a chocolate bar and get some rest. One of the reasons behind ego depletion is our brains eating up the reserves of sugar in the body. By replenishing the supply via a quick source like a chocolate bar, you can restore balance and improve your decision-making abilities and willpower.

Take your time

Decision overload is directly tied to the timeframe you have to make decisions in. If you are pressed for time, choice overload hits harder: the decision is more difficult, more stressful and in the end, you are less satisfied with the result.

But the time pressure is rarely there for real. Sometimes we create it ourselves by wanting the decision to finally be over with so we can leave the shop or website with the product. Other times, there is time pressure from the side of the seller, created via time-restricted offers or sales.

Research indicates that you will be less satisfied with the decisions you make in the time pressure scenario and will be more likely to experience buyer’s remorse. This phenomenon occurs after a purchase when your brain feels like it didn’t make the best choice possible and starts to exaggerate every negative about your purchase.

Completely viable options might start to seem like a bad deal, and your overall happiness, not just with the transaction, but also with the process, will deteriorate significantly.

The best thing you can do in this situation is to just walk away from the offer and take your time. Give yourself more time to process and weigh all of the options before making a decision, but don’t hang around too much.

By introducing a comfortable deadline for making a decision, you can cut down on regrets while still easing the pain of the decision-making process.

By introducing a comfortable deadline for making a decision, you can cut down on regrets while still easing the pain of the decision-making process.

Get other opinions or the help of an expert

The basic premise of choice overload is making a decision in a domain that is somewhat unfamiliar to us. The more you know about the subject, the less overload you feel.

Bringing an expert on board while deciding can pass some of the “burden of decision-making” onto the shoulders of a more knowledgeable person while you learn a thing or two yourself. Experts can see through the complexity and simplify the decision enough to enable you to make a good decision which your brain will be satisfied with.

This can take many shapes and forms – from community reviews on the internet, through getting help from the salesperson on the spot, all the way to contacting an expert and taking them shopping with you (like taking your green-thumbed neighbor to the garden center when picking a new lawn mower).

Case studies on choice overload

Cutting down the menu in Mitchells & Butlers led to increased sales

The more people a restaurant caters to, the more money it will make … sounds like a reasonable proposition. So, when successful pub and restaurant chain Mitchells & Butlers approached Cowry Consulting, a company specialising in behavioral science, with the task of increasing average spend by 4 pence per head, the last thing they expected was to cut down the menu.

But that is exactly what the behavioral experts from Cowry suggested.

First of all, they reduced the number of items on the menu. Then they chunked the remaining dishes by courses (starters, soups, mains, desserts), giving each course equal space in the menu. On top of that, they made each section easily skimmable by clearly grouping foods by category – such as vegan, meat, or fish dishes.

Source: Cowry Consulting

With these changes, and 2 others, Cowry Consulting was able to increase average spend per head not by 4, but by an incredible 13 pence. It might not sound like a lot, until you realise that with more than 150 million dishes served each year, it could mean up to 19 million pounds in additional revenue, just from changing up the menu.

Netflix bypasses choice overload with social proof

What can you do if people hate to choose from a myriad of options … but having literally thousands of movies and shows is your biggest selling point? Netflix cleverly bypassed declining watch times during the pandemic through several tricks.

Social Proof

Social proof is our tendency to be influenced by what others do, how they think and behave. Social proof works particularly well in situations of uncertainty.

First of all, there is social proof – which is exactly like getting an expert opinion. Netflix uses 2 variations on this: “Trending now” and “Top 10 in your country”.

By offering you a list of shows most people like right now, they not only get you in on their bestsellers, but also give you a slight FOMO. These are the shows everyone will be or already are talking about. Do you really want to miss out on them and be the outsider who hasn’t seen the latest phenomenon?

Of course, you don’t.

And also – how bad can the shows be? Everyone is watching them – and everyone can’t be wrong. Social proof takes the burden of choice off your shoulders and redistributes it to the wisdom of the crowd. The choice is made that much simpler in an instant.

Source: Netflix

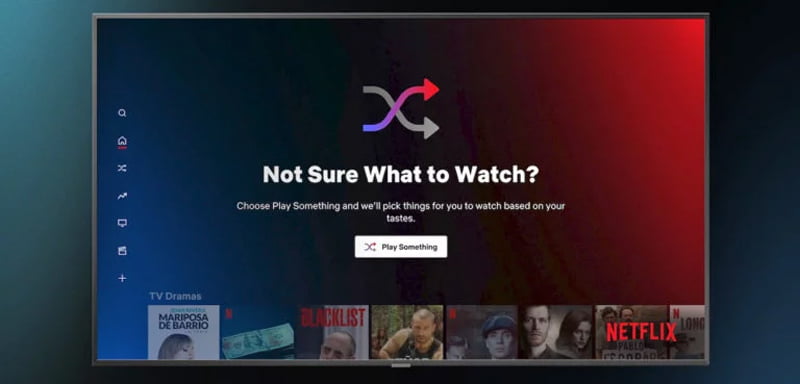

And then there is the “Play something” option.

This one eliminates decision-making altogether, reducing the choices to ZERO … which might seem like a bad thing. Until you realise that to get to this option, you have to deplete most of the other options.

The timing is great – you are so exhausted by the decisions that being served a “good enough” show is all you crave right now. And Netflix delivers, just to keep you on the platform.What other tricks do they use to reduce friction and increase watch times? Read this case study by gamification designer Oliver Simko and learn the tricks Netflix hide up their sleeves.

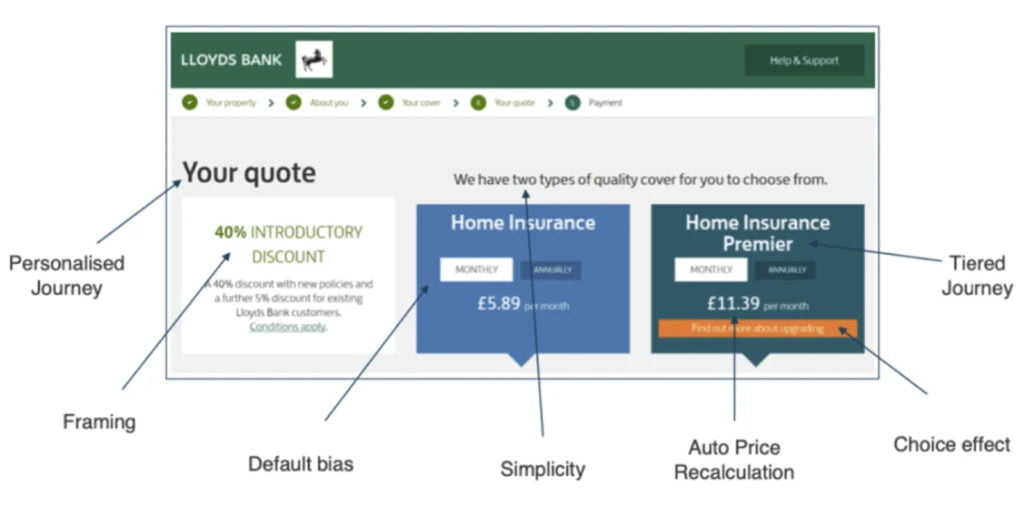

Lloyds Bank insurance leads you down the path of least resistance

Sometimes even 3 options can be too much – as the online department of Lloyds Bank insurance division experienced first-hand while fine tuning their offer.

Having only one option felt too limiting, but three options raised an undesirable question – what was left out in the cheaper options? Or what am I getting extra by choosing the most expensive one?

Either way, people were not particularly satisfied with whichever option they chose, instead feeling like they were either paying too much or missing out on important cover.

And so, they settled on 2 options: a basic one and one with extras.

There was an option for the “choice fatigued” who just wanted to be done with the process, as well as one for customers who wanted to be fully in charge.

Source: Lloyds Bank

What other techniques did they use, and which experiments fell completely flat despite seeming promising at the start? Learn more in this case study by Dectech.

How to use – or misuse – choice overload in business?

Chunk a complex decision – choice overload in hospitality

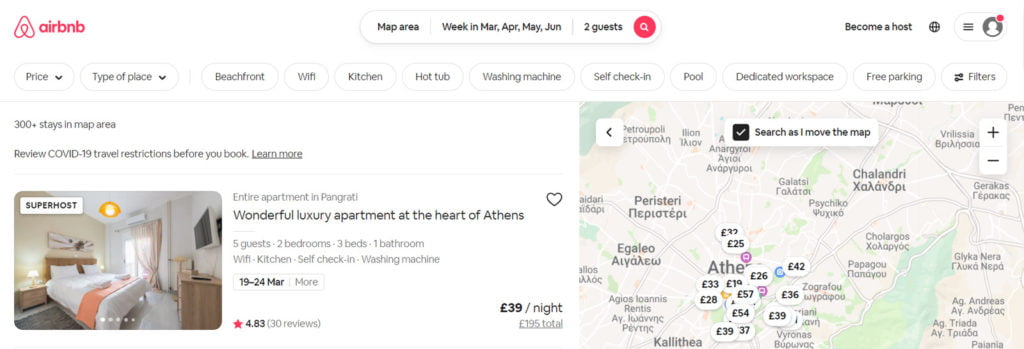

One effective way of fighting choice overload is called “chunking”. You’re familiar with it for sure – it’s used everywhere from bookshops to Airbnb. This approach lies in chunking decisions into several distinct steps, making them easier and more manageable.

Let’s look at an example.

Imagine you’re planning a vacation in Athens and need a place to stay.

You hop on the Airbnb site to find something suitable, punch in “Athens” and … you’re flooded with several hundred offers. A typical choice overload situation.

But Airbnb does not leave you hanging – they know how overwhelming it might feel. And so, they immediately offer you a set of thematic filters to break the offers down into understandable “chunks,” each one narrowing and specifying your selection more and more.

Do you want a place on the beach, or in the center? With a kitchen, or just a place to crash at night? The difficult process of picking the right accommodation is suddenly reduced to a series of simple yes or no statements through several buttons, leaving you with a dozen or less offers that are easy to scan through. A big photo on the front of each offer immediately gives you the vibe of the accommodation, and you’re brought into the mood of “feeling” the right place instead of making a difficult “rational” decision.

All in 7 or less clicks.

Source: Airbnb

Thanks to being led through the choices step by step, you don’t feel overwhelmed by the options, but instead, feel a sense of progression with great closure at the end of it – so you enjoy the result, as well as the process much more!

Categorize choices – choice overload in restaurants

Decision-making is not the only thing that can get bunched into logical groups – the choices can too.

You have probably seen this hundreds of times – when shopping in a bookstore categorized by a genre (such as Young Adult or Business) or picking food from a menu chunked by courses.

Exactly like in the case study from the Cowry Consulting, chunking the array of food choices on the menu can be a great way to incentivize people to order a full meal, including a starter and dessert, increasing revenue by a significant margin without actually changing up the food on offer.

Misusing choice overload – opting for a default option raised revenue by €1500 per car

A field study by a German car dealership showed an interesting way that choice overload can be misused to manipulate people into ordering a more expensive version of a car – by simply reordering the sequence in which people made the decisions.

Instead of offering the most important decisions upfront, the most fatiguing ones were offered early in the process. Instead of choosing the type of engine or gearbox combination, people were confronted with decisions about the style of wheel rims and the color of the interior. With dozens of options and the perceived importance of the decision (you wouldn’t want to drive around in a shoddy-looking interior), those least-important decisions drained the willpower of customers early on.

As a result, when it came to the later costly and important decisions about the engine, people were already ego-depleted. Many simply opted for the predefined option, which was higher quality, but also more expensive.

The result of this simple choice architecture trick was staggering: it increased the average spend on the car by €1500.

Discover 2 more ways to eliminate choice paralysis in your business in our Choice Overload e-book.

Summary

What is choice overload?

Choice overload is an adverse effect of too many available choices on our decision-making ability.

We are always trying to compare and choose the best option when presented with a decision. But if there are too many options that we can’t easily differentiate between, our ability to make a good decision is reduced by this overload of choices, as is our satisfaction with the final decision.

Choice overload is most likely to happen, when deciding in an area we are not knowledgeable enough about, and its effects decline the greater the familiarity with the subject.

How to avoid choice overload?

Replenish your willpower – when making decisions, our brains “use up” our ability to make good decisions. After a load of decisions, we deplete our decision-making resources, and our brains start to simplify things and go with the default option.

To replenish your decision-making ability, you have to increase your glucose levels and “feed your brain” with the resources that get used up when making decisions.

Take your time – time pressure can make decisions seem harder and more important than they actually are. If you’re feeling pressured, just take a step back and take your time.

By doing this, you distance yourself from the decision and make it easier for your brain to have a fresh perspective on the problem and options presented.

Get an expert opinion – If you feel you cannot effectively differentiate between the options presented, get an expert opinion. Strangers on the internet, a sales representative or a knowledgeable friend can be great gateways to knowledge that will ease the decision-making process.

You don’t have to follow the opinion of an expert – there is always the option to ignore them and go with your gut. But the information and the different perspective an expert brings to the situation can ease the feeling of “burden” from the decision you have to make.

How to reduce and use choice overload in business?

Chunk it up – Make it easy for your customers to decide from a large number of options by gradually building the decision up.

Don’t let buyer’s remorse sink in – assure your customers they have made the right choice. Show them positive feedback from other people, emphasise their freedom to choose – or return the product if they want.

Use the path of least resistance to guide your customers – When your customers are drained of willpower, they will often opt for the default option. Use this to your advantage and build the default product in such a way that will satisfy most of your customers. Remember the case of Lloyds Insurance and their 2-option sales funnel – either you are too overwhelmed and go the path of default insurance, or you want to choose and go through the more painstaking process of creating your perfect package.