How To Understand What’s Stopping Customers From Doing What You Want Them To Do

One of the most common mistakes marketers make is focusing too much on motivating customers; when in reality, they should be asking themselves: “What’s keeping customers from doing what I want them to?”

In this article, you’ll discover:

- How you can get out of the habit of focusing too much on persuasion and spend more time understanding why people aren’t doing what your business or organisation wants them to do;

- A useful framework to help you identify different kinds of barriers or headwinds that make decision-making and behavioral changes more difficult; and

- Examples of how an understanding of these barriers helped organizations achieve their goals, plus tips on how you and your team can do the same.

What might prevent you from reading this article?

Maybe you’re short on time. It looks like it could take you several minutes to read it (in actuality, it should only take you 5 minutes).

Maybe you think it will have nothing to do with your business (actually it will show you a quick and easy-to-use framework that dozens of companies have used to understand the barriers that prevent people from buying their products, whether these companies sell apparel, life insurance policies, or pharmaceuticals).

Or maybe you got an alert about this article on your phone, but you hate reading long text on a small screen, and you won’t be back home or back in the office for a couple of hours. If that’s the case, we recommend e-mailing yourself the link to this article so that it will be at the top of your inbox when you get back to your desktop computer.

Instead of focusing on why you might read this article, we started by thinking about reasons why you might not.

We may not have done the best possible job of getting you to read this article (although if you’ve got this far our chances of you finishing it are reasonably good), but we did do something very important. Instead of focusing on why you might read this article, we started by thinking about reasons why you might not.

Think long and hard about the “why nots”

In her excellent new book, “How to Change: The Science of Getting From Where You Are to Where You Want to Be”, Katy Milkman — one of the shining stars in applied Behavioral Science (she’s a Wharton professor who’s worked with dozens of startups and giants like Walmart and Google) — extols the importance of understanding barriers, or obstacles as she prefers to call them. Before embracing Behavioral Science, she studied engineering. Here’s what she says:

“An engineer can’t design a successful structure without first accounting for the forces of opposition (say, wind resistance or gravity). So engineers always attempt to solve problems by first identifying the obstacles to success. Now, studying behavior change, I began to understand the power and promise of applying this same strategy.”

The question that keeps us awake at night is: “What’s it going to take to make people act?” But we really should be asking ourselves: “What’s keeping people from doing what we want?”

In general, most of us working in marketing and business don’t have the benefit of an engineer’s perspective. We see our jobs as developing programs that encourage prospective clients to try our products, or encourage our customers to keep buying them. We spend hours and days – even weeks and months – trying to understand what might motivate them to buy, and how we can come up with ideas that will spark that motivation. The question that keeps us awake at night is: “What’s it going to take to make people act?”

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

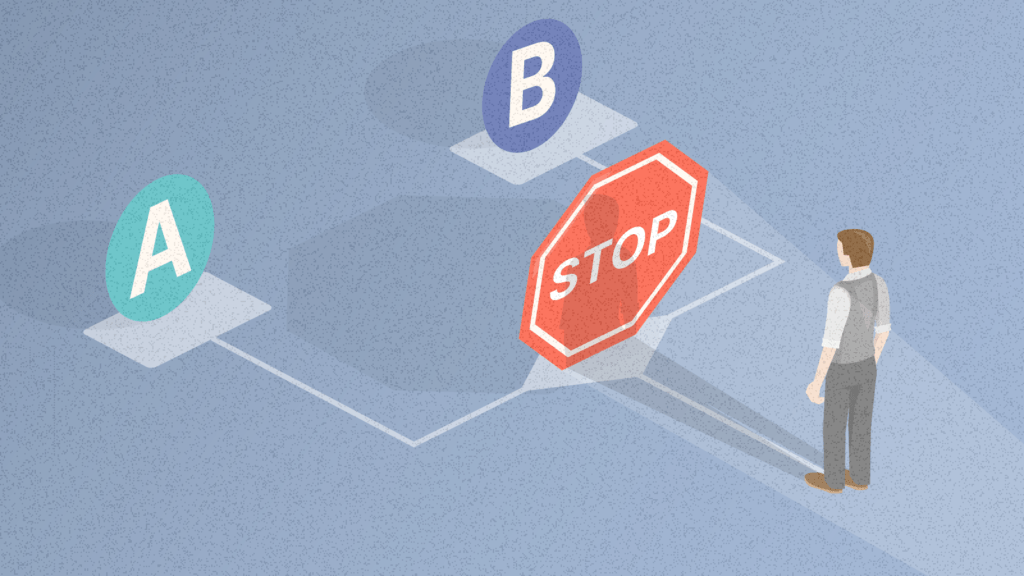

But as it turns out, obsessing over that question might make us blind to the question we really should be asking ourselves: “What’s keeping people from doing what we want?” It’s something we should be asking before we even get started on people’s motivations and reasons to buy something. In their book, “Why People (Don’t) Buy: The Go and Stop Signals”, marketing professors Amitav Chakravarti and Manoj Thomas suggest that:

“Effective marketing entails strengthening GO signals and weakening the STOP signals”.

But most marketing effort (both in terms of the time spent by marketing teams and their substantial investment in marketing activity) is focused on strengthening the GO signals. One reason for this is that as adults, we often see our value as builders, or “adders.” In a recent paper published in Nature, researchers investigated this. Their research suggests that:

“People systematically default to searching for additive transformations, and consequently overlook subtractive transformations.”

The authors continue:

“Additive ideas come to mind quickly and easily, but subtractive ideas require more cognitive effort. Because people are often moving fast and working with the first ideas that come to mind, they end up accepting additive solutions without considering subtraction at all.”

Taking away barriers and reducing stop signals just doesn’t seem as sexy as a high-profile program to drive demand, and so we tend to not spend enough time on it, but evidence suggests that if we prompt ourselves and our teams to consider solutions that remove barriers, they’ll do just that.

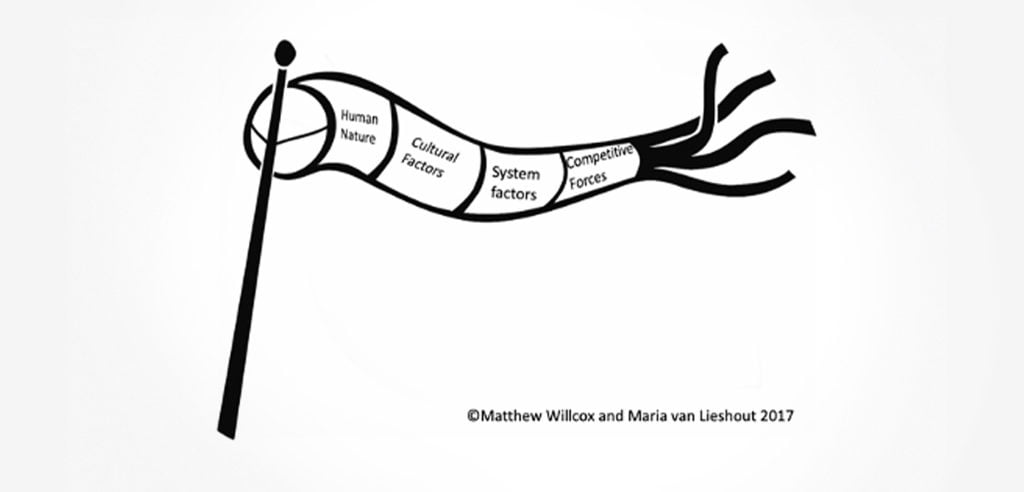

But most organizations lack the tools or processes to do this. And the barriers or “headwinds” preventing customers from taking action are many and various. Only after identifying them all can you really prioritize which ones to subtract, or at the very least mitigate. A tool developed by the Business of Choice helps marketers take a systematic approach towards identifying the range of possible signals and circumstances that consciously, or subconsciously, make inaction easier than action.

These “headwinds” can be broken down into four groups: Human Nature, Cultural Factors, System Factors, and Competitive Forces. Here’s a simple visual of a windsock to remind us of the different headwinds.

Human Nature

This “bucket” includes many of the heuristics and biases that affect people’s choices, and we are covering it first because it will very often (but not always) provide the keys to unlock barriers in other categories. When using this tool for a life insurance company, a behavioral analysis of market research suggested that a significant barrier preventing people from taking out life insurance was Optimism Bias.

Optimism Bias leads us to believe that unfortunate things are less likely to happen to us than they are to other people. The recommendation to the client was to reduce the effects of this headwind and focus more on the positive benefits of life insurance (peace of mind, the idea of legacy) rather than focusing on the bad things that could happen, thereby trying to burst the bubble of their optimism bias.

What can you do about it?

If you’re reading articles about behavioral economics, then you’re already taking one of the most important steps — which is to familiarize yourself and your team with the subconscious processes that affect human decision-making. As you and your team become more “behaviorally-attuned”, you’ll also become more aware of how human nature might be acting as a headwind.

Avoid falling prey to survivorship bias. Survivorship bias makes us more likely to notice tactics or programs that have succeeded, as they tend to be more visible and more enduring than those that have failed.

Negative social proof

Be careful about negative social proof. If you want people to do something, don’t tell them that the majority isn’t doing it.

Reviewing approaches that have failed from a behavioral perspective can reveal cognitive processes that might be impeding behavior. For example, an unsuccessful approach that created negative social proof about an insurance product (“only 12% of California households have earthquake insurance”) not only teaches us to avoid creating negative social proof, it might also lead us to think about how the absence of positive social proof might be a barrier when considering earthquake insurance.

Cultural Factors

The same life insurance company had an established business in Asia, but like the category as a whole, growth in Asian countries had been slower than expected. One reason for this is that in general, Asian cultures tend to be more interdependent than independent. In many countries in Asia, the cultural norm is that families will take care of each other. The interdependent nature of most Asian cultures means that extended family will help provide for family members in times of distress and loss.

This powerful cultural value is an inhibitor to investing in life insurance. Reframing life insurance as a way of contributing to this supportive family network rather than replacing it made the idea of life assurance more palatable to Asian audiences.

When we say “cultural factors,” we don’t just mean macro-cultures like the example above. The spoken and unspoken codes of a tribe often provide more “don’ts” than “dos.” Being a member of a specific profession (be it a cardiologist or network engineer) can provide a cultural framework that affects decision-making. You could argue that the creative, building culture of marketing is a barrier preventing us from giving barriers the consideration they deserve!

You can read a fascinating case study about addressing cultural barriers between women and men in this article on How One Small Change in a Tampax Tampon Design Made a Big Difference for Customers

What can you do about it?

Make sure you have both the perspectives of insiders and outsiders. If your team consists of people from a variety of different cultural backgrounds and experiences, you can use their innate understanding of cultures they’re familiar with to detect and understand potential cultural barriers.

As such, a curious outsider will also often question and bring to light aspects of culture that might be inappropriate to discuss, or aspects that are simply too ubiquitous to have ever become invisible.

Focus your efforts on the most important aspects of your strategy and explore whether cultural aspects might be influencing them in a negative way.

Systems/Infrastructure

When we say “system factors,” we mean hurdles (that sometimes might feel more like brick walls) like market structures, government or industry regulations, and infrastructure or “hardscaping.” With life insurance in some Asian countries, the structure of the financial sector makes creating channels to sell life insurance very difficult. While developing their own was a possibility, it would have been a long, hard road, so the client sensibly took the approach of working with existing financial institutions in the region.

In another example, The Business of Choice was working with an NGO and human-centered design firm aiming to improve access to family planning clinics for young women in East Africa, one very basic barrier was how these young women could safely get to a family planning clinic when the nearest one was across town. One of the design firm’s main recommendations was to create opportunities for female-owned and operated bajas (three-wheeled taxis).

One under-used research approach is to ask people to show you how they would go about making a choice, or carrying out a behavior

Norway is currently one of the leading countries in the world in terms of electric vehicle (EV) ownership, with over 50 EVs per 1,000 people. But less than a decade ago, Toyota was struggling to sell its Prius hybrids outside of major metropolitan areas. One reason is that as a long and narrow country, people who might be interested were not always within a convenient distance of a Toyota dealership that allowed prospective drivers to test a Prius.

Social proof

Social proof is our tendency to be influenced by what others do, how they think and behave. Social proof works particularly well in situations of uncertainty.

An inspired program by Saatchi and Saatchi Oslo overcame this barrier by putting out a casting call to existing Prius owners and asking them if they would let prospective Prius drivers test drive with them.

The existing owners were featured on social media so that people interested in testing a Prius could find someone near them. The program cleverly uses a number of psychological effects — social proof in that it shows you that people near you and who likely have some of the same connections as you drive a Prius; and choice-supportive bias (the tendency to retroactively ascribe positive attributes to an option one has selected) in the owners, making them far more convincing than any sales person at a Toyota dealership could ever be!

What can you do about it?

One under-used research approach is to ask people to show you how they would go about making a choice, or carrying out a behavior (unfortunately, so much more research is conducted on understanding people’s motivations than on understanding how they might go about deciding and fulfilling their decision).

Simply asking people to map out the process of choice and discussing this with them will reveal headwinds that could derail the potential chooser on their journey.

Simply asking people to map out the process of choice and discussing this with them will reveal headwinds that could derail the potential chooser on their journey. In a project to understand the decision-making process of cardiologists prescribing (or not prescribing) a new form of treatment, this research approach revealed that one of the tests necessary to get the disease “markers” was in a test “panel” that cardiologists seldom used. Simply providing information about the panel helped overcome this barrier within the system.

In regulated industries, it’s good to have a sense of regulatory barriers early on in the process of creating marketing and influence programs. In pharma companies, it’s not unusual to have regulatory specialists embedded in the marketing team, something that even companies in less regulated businesses could learn from. It’s a bit like using Waze when you’re driving. Better to know about a road closure early so that you can plan an alternative route rather than spending hours in a traffic jam.

Competitive Forces

The nature of a category and the actions of competitors can create formidable barriers. This doesn’t mean you should obsessively focus on every competitor’s action. But it’s important to think about how your competitors might be creating headwinds that make what you’re selling a more difficult, less intuitive, or less rewarding choice.

If your competitor is well-established and the leading brand, it’s important to understand that they benefit from the availability heuristic, which means they’re “mentally available” and so top-of-mind that other options don’t get looked at.

If you recognize this, you may choose to use your competitor’s dominant position to your advantage, which is exactly what Avis did back in 1962, with their famous ads that read: “When your No. 2 you try harder” (click here to read an article and watch a short video that explains some of the behavioral insights behind challenger brands).

If your competitor is the leading brand, it’s important to understand that they’re “mentally available” and so top-of-mind that other options don’t get looked at.

Moving from renting cars to buying them, a decade ago, Korean car manufacturer Hyundai discovered a barrier that was preventing US car buyers from choosing Hyundai over their more established competitors like Honda and Toyota. Apparently, these Japanese brands had a more-or-less guaranteed resale value. Car salesmen at Honda and Toyota made the most of this, creating decision uncertainty (this is often driven by a cognitive bias called ambiguity aversion) amongst anyone who might be considering purchasing a Hyundai.

Hyundai took this head-on by creating a guaranteed trade-in program, which guaranteed a minimum value for trade in. This plus other aspects of the Hyundai Assurance program helped Hyundai move from a share of just under 3% of the US car market in 2008 to one of over 5% in 2011.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty is a situation when your customer has incomplete or missing information. A situation when their questions, concerns, and fears aren’t answered.

A competitor and the choice barriers they represent can be sources of opportunity and bigger brand energy. This is exactly how Avis used the barrier of Hertz’s dominating position all those years ago.

But just as a skateboarder uses the obstacles in their terrain to give them the speed and direction for their moves, he or she knows the importance of understanding the nature of the obstacle before using it as a launchpad for tricks. A phrase skaters use is “learn your obstacles and their possibilities.” Similarly with your competitors — if you understand what is making the decision to choose your brand or business over theirs more difficult, you might also find some opportunities for leverage.

What can you do about it?

Competitive understanding and analyzing competitors’ claims is often seen as a boring chore and usually delegated to junior team members. One consultancy firm that specializes in competitive analysis uses an approach more like that of a private investigator. They carry out research specifically with competitive purchasers, pose as potential purchasers of competitive products, and sometimes even interview with ex-employees of those competitors. Follow their example, and think and act more like Magnum PI than like an intern!

In short, why people might not do what you want them to is the question you and your team should be asking before you even consider how you can motivate them.

Key Takeaways

- Before you think about how you can get people to do something, think about why they might not do it.

- To reveal these barriers and headwinds, you need to be systematic. The “Barrier Windsock” can act as a reminder of the different kinds of barriers: human nature, cultural aspects, systems/infrastructure, competitive forces

- Be a guinea pig — go through the decision-making and purchase process yourself; then document anything that gives you pause for thought, creates uncertainty, or requires mental or physical effort.

- When it comes to understanding competitive barriers, get your gum shoes out and think like a private investigator!