Mental Accounting – Everything You Need To Know

Mental accounting determines how consumers spend, budget, and save. Learn its benefits, drawbacks – and how to unlock it.

Article content:

Defining mental accounting

Think about what you would pay for a dinner on holiday in Rome versus at home.

Likely, a nice view of the Colosseum, a friendly waiter and the promise of delicious bona fide Italian pasta would persuade you to spend a large sum there without regrets. At the same time, you would leave your local restaurant upset if you had to pay out the same sum there!

Where or what you pay for shouldn’t matter to your spending. But it does!

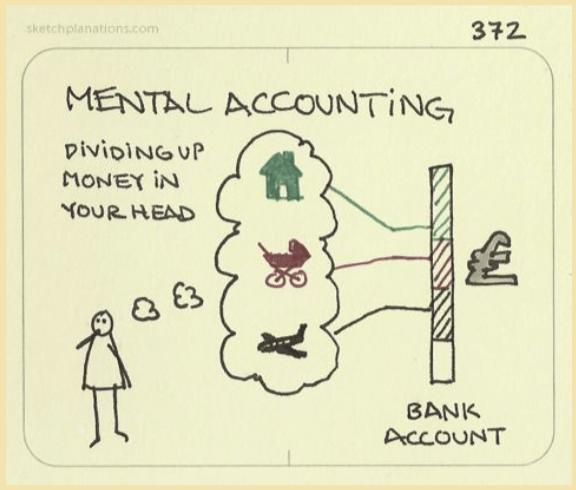

Mental accounting is the tendency of humans to create mental labels for money, based on its origin or deemed purpose.

Mental accounting is the tendency of humans to create mental labels for money, based on its origin or deemed purpose. Money itself is interchangeable, but through mentally dividing it into labels, we don’t see it that way. Although these decisions can seem rational, they are often governed by emotions, and can be misleading or even damaging.

For example, you might be on a budget at home, but will indulge your expensive desires in Rome, because you are on holiday. While you perceive the circumstances as being different, the effect on your bank account will be the same: devastating.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

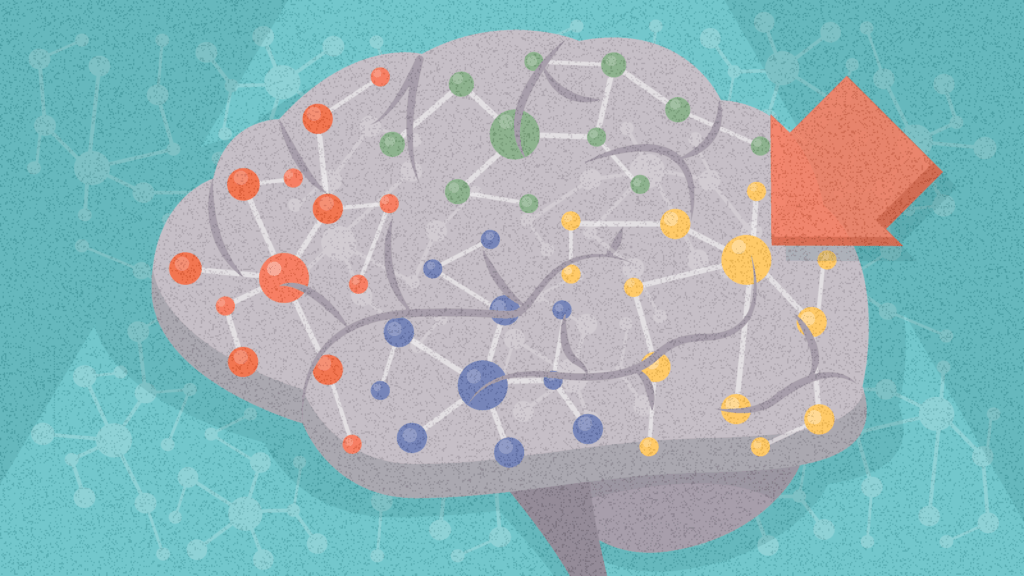

How does it work?

You can imagine mental accounting as the filing system by which your brain keeps track of things. While we categorize information based on commonalities, mental accounting allows us to actually navigate and recall the retained information.

Without mental accounting, a person would need to consider all of their present and future wealth, before deciding whether to go out for dinner. This process would obviously be unsustainably time- and energy-intensive, so our brains invented mental accounting as a shortcut.

It makes us faster in a variety of ways, such as determining what time period matters for a decision. For instance, when we’re buying a new pair of sneakers, we don’t need to consider our estimated expenses for the entire year, just how much money we have left till our next paycheck. Through mental accounting we also determine what our budget is for other shopping related expenses, and whether the price we would pay for something is fair.

The three streams that make up mental accounting were summarized by Nobel Prize laureate Richard Thaler in his seminal paper Mental accounting matters.

He outlined three things:

- Consumers care more about whether a transaction is perceived as advantageous or fair, than the actual price of the product. For instance, paying $5 for a bottle of water would be normal at a cinema but would seem excessive at the grocery store, even though the bottle of water is the same in both situations.

- The frequency with which we check our account balances affects the evaluation of our mental budgets and spending. If we check our balances monthly, a small recurring investment profit can lead us to increase our monthly budgets, because the profit boosts our overall balance at the end of the month. In contrast, if we review our balances yearly, the extra monthly income wouldn’t affect our budgeting plans, meaning we would spend less over the year.

- Individuals track their financial activities by grouping them into mental categories with predefined budgets. The grouping criteria are arbitrary. You could organize expenses by their origin (regular or windfall income), their purpose or goal (entertainment or nutrition), being of a similar magnitude (€10 or vast sums), the same payment method (credit card or cash), or occurring in the same location. (electronics store, holiday resort)

Is mental accounting a problem?

Scientists have found that mental accounting has some clear benefits.

Just as you can find things much easier in a tidy, organized room than in a messy one, mental accounting helps us recall information quicker. It is, for example, what allows traders to make quick calls on buying or selling in high-stress situations.

It is also crucial in how people handle money on an everyday basis. By assigning money for its intended purpose, people oversee their spending and regulate themselves. This can help people to resist the temptation of spontaneous purchases. If the money in your pocket is earmarked for groceries, you won’t go off and buy yourself a pair of jeans with it.

Similarly, in cases of uncertainty, mental accounting helps us allocate resources between competing needs and desires. If you know the main expenses you have in a month, you can decide whether taking a spontaneous trip is realistic or even affordable. Through this evaluation, mental accounting can stop us from irrationally blowing money on our desires to the point where we run out or even become indebted.

Source: Sketchplanations

At this point, you might be thinking:

Well great! Mental accounting seems to be a blessing in disguise! Why should I care about it?

Unfortunately, as with most things in life, mental accounting is neither good nor bad in itself. Its effects can benefit you in life, but they can also hinder you by making your decisions less accurate and irrational.

By creating mental accounts for money, we can lock ourselves into inflexible budgets, where we won’t adjust for differences between our expected and actual expenses. A great (and slightly worrying) example of this is the actor, Dustin Hoffmann.

He took budgeting very seriously by placing his money in actual jars according to their intended purpose. When his budget for food became empty, he asked his friends for lunch money instead of redistributing it from his otherwise full jars. See the full clip below.

Source: YouTube

An additional problem with fixed mental labels is that small sums or expenses which don’t fit clearly into one category can easily slip through the cracks. If you are an avid daily consumer of coffee, you probably don’t give the cost of your coffee a second thought. However, when looking to purchase a necklace for the equivalent price of your coffees over a month, you might do a double take.

Alternatively, when you are purchasing work clothes, the expense might be classified ambiguously to your work or clothing budget. Individuals motivated to circumvent self-control can assign the expense to whichever mental account allows them to overspend more.

Both cases illustrate how mental accounting is malleable and susceptible to (un)intentional manipulation and based on emotional factors rather than rational ones.

This effect is especially prevalent when we face so-called windfall gains.

This is because windfall gains are unaccounted for in our budgeting plans, and their size and unexpectedness lead us to spend them impulsively rather than keeping them.

Windfall gains are instances where you receive money unexpectedly, such as getting a bonus, winning the lottery or finding money on the street. In all three cases, you are more likely to spend this money on something random and spontaneous, like going on an extra holiday, buying a designer jacket or having an expensive dinner, even if you would avoid these activities from your normal income.

This is because windfall gains are unaccounted for in our budgeting plans, and their size and unexpectedness lead us to spend them impulsively rather than keeping them.

This behaviour is so typical that it even made it onto the television series Futurama. Watch the clip below.

Source: YouTube

You should also be wary of your mental accounting, as it can be tricked. Credit card companies can manipulate this by offering to defer payment for products to a later time. Generally, payments by card are less detectable by us, and people often tend to forget about them until the bill arrives. Delayed consumption also makes mental accounting inaccurate, as we don’t sense the pain of paying instantly.

While this service can be incredibly useful at times, it can also lead to reckless spending and devastating consequences. Particularly financially vulnerable individuals, who often also have low financial literacy, can be tempted into overspending and then be devastated by high interest payments. You have to be careful with mental accounting to avoid such pitfalls.

Mental accounting experiments

Theater ticket study

Mental accounting was first hypothesized by two individuals whom you might recognize: Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. In their effort to establish the field of Behavioral Science, they noted that people engage in “psychological accounting”. Here, money is managed based on its emotional value instead of its fiscal one.

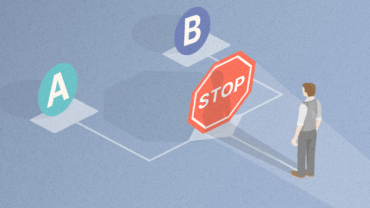

They proved this preference in their now infamous theatre ticket study. Participants in the experiment were asked whether, upon deciding to see a play, they would buy a $10 theatre ticket if:

- they had just lost a $10 bill on the way to the venue

- they had just lost a presale theatre ticket of similar value on the way to the venue

As expenses are grouped by spending category, losses in that category affect future consumption there, while a “labelless” loss (cash) has a lower influence.

In an economic sense, the two options are identical. Hence, people should have the same response, regardless of whether they are given situation A or B. In either case, if they buy the theatre ticket, they leave with $20 less in their wallet.

Unsurprisingly, as this is an article about human biases, the results were quite different.

88% of respondents reading about the $10 dollar bill wanted to buy a second ticket. In contrast, only 46% of participants who “lost” the presale ticket were willing to buy a second ticket.

The explanation between scenarios A and B is what we call mental accounting. As expenses are grouped by spending category, losses in that category affect future consumption there, while a “labelless” loss (cash) has a lower influence. While the term mental accounting was coined later by Richard Thaler, the existence of mental accounts was first proven in this experiment.

Splitting and grouping experiences

An extension to mental accounting was completed by three American psychologists in 2021. Building upon the work of Richard Thaler, they examined how people evaluate (dis)similar losses and gains, and what their preferences are over the timing of these outcomes.

Thaler had previously explored this relationship. He theorized that people would prefer to evaluate gains separately to maximize pleasure, but group losses in the same mental account to minimize pain. He called this behavior hedonic editing. Disappointingly, he found that the theory only partially worked. People did try to mentally segregate positive events to make the pleasure last longer – but they did the same thing for losses!

Wonder why?

Then keep reading!

It is this question, and what people’s exact behavior then is, which Ellen Evers, Alex Imas, and Christy Kang attempted to answer through a series of experiments.

They asked participants to determine in what order and when certain events should happen to them in fictitious scenarios and in real life. For instance, individuals were asked when they would prefer to learn about the cost of their car insurance increasing by $10, if in the morning they had just found out that their milk had gone sour. They could choose to experience these events on the same day or a week apart.

Variations of such scenarios were run over 6 different experiments. The events could be positive (getting a good grade in an exam) or negative (getting root canal treatment) and were shuffled depending on their nature (gain/loss) and similarity. (e.g. physical pain vs financial pain)

So, what did they find?

That similarity heavily influences what we group in a mental account.

The more similar certain events are, the more likely people are to categorize them as the same event and place them in the same mental account.

The more similar certain events are, the more likely people are to categorize them as the same event and place them in the same mental account. In turn, the more dissimilar events are, the more people tend to categorize and evaluate them separately from each other.

Additionally, the results showed a clear pattern in how we mentally edit pleasurable and unpleasurable events.

If we are faced with a gain and the sources of joy are similar, we prefer them spread out across time, while if they are dissimilar, we want to experience them at the same time. This makes sense, as making a solid profit from your stocks every month is preferable to a large, but one-off sum once a year. Similarly, getting your dream job and winning £60 on the lottery is more fun than experiencing these separately, as the combination makes that day extra special.

If we are faced with a gain and the sources of joy are similar, we prefer them spread out across time, while if they are dissimilar, we want to experience them at the same time.

If we are faced with losses, we ease the negative experience by grouping them when they are similar and occur around the same time. This way, we can comfort our nagging subconscious, by blaming the losses on bad luck or any other explanation we find adequate. In turn, if losses are dissimilar, we prefer them to be spread across time.

If we are faced with losses, we ease the negative experience by grouping them when they are similar and occur around the same time.

Somehow, all your stocks starting to plummet at the same time is less painful than each one nosediving consecutively. On the other hand, seeing your portfolio turn red and getting your car stolen on the same day is much worse than these events happening half a year apart.

How to overcome mental accounting

Annoyingly, biases are very persistent and hard to get rid of.

That said, you probably shouldn’t even try to eradicate mental accounting completely! After all, it evolved to keep us accountable (pun intended) and responsible for our actions. Instead, try to use it to your advantage and use the following tricks to overcome any of its drawbacks.

Write down your budgeting

This tip is as easy as it is effective. Stop keeping everything in your head, where it is susceptible to your changing moods or desires. Instead, capture it in a written format and transform your mental accounting notes into something tangible. There are various online tools available which, if you enter your goals into them, can help you take your financial overview to the next level. Not only do they keep track of your incoming and outgoing finances, but they can also help you get financially organized!

While this might seem like a minor factor, a 2015 study found that only about 56% of individuals surveyed actually report having a household budget, meaning that 44% of the sample are spending money without having any system of checks and balances. In a similar study, only 39% of people reported having spent a significant amount of time developing a financial plan. So, even if a budget exists it is likely not protected from any financial turmoil.

If you recognize yourself in these samples, you definitely should go ahead and take a second look at your financial plans. It is a crucial part of life and a huge factor in overall happiness!

Mark your savings visually

Recent research has found that physically segregating funds and visually earmarking them with reminders significantly increases the rate of savings. Additionally, budgeting for intended use is actually underpinned in its effectiveness in empirical studies, where dedication increases when accounts are notionally earmarked for a specific purpose.

Remember Dustin Hoffmann? He actually might have been onto something back then with his system of jars. Obviously, it’s important to avoid being too inflexible with your budget, but distinguishing your rainy-day fund in its place and appearance is definitely worth a try.

Make a plan for unexpected income

Remember windfall income and how we spend it on spur-of-the-moment purchases? This tends to happen as windfall income feels like “free money” which is not accounted for in our mental checklist due to its unexpected nature. For example, we might know of the existence of an incoming tax rebate, but we do not know its exact sum. So, a larger than expected sum is exactly the impetus we need to blow it on a spontaneous trip or a new designer jacket.

Dissatisfaction with our desires motivates us to find ways to circumvent this self-imposed control, increasing our chances of using “creative” mental accounting.

One way to deal with this is by prepping for the unexpected. Take some time to come up with a strategy for a windfall situation. Would you spend half of it, but deposit half of it in your savings account? Would you place it all in an investment portfolio? There is no right answer, but it should be a balance which leaves you satisfied. Dissatisfaction with our desires motivates us to find ways to circumvent this self-imposed control, increasing our chances of using “creative” mental accounting.

Find external accountability

A common idea for increased financial responsibility is to find an accountability buddy. As the topic of money is often treated as a taboo subject and not commonly talked about in public settings, this can lead to the compounding of mental accounting traps.

Couples with joint accounts are more likely to spend on essential goods, rather than blowing their money on luxury goods, as the act of justifying expenses leads to higher resistance to impulse purchases.

Remember, two heads are better than one, and if faced with a roadblock, talking about it can help resolve it easier than mulling it over individually. This notion is underpinned by the findings of a recent study. It found that couples with joint accounts are more likely to spend on essential goods, rather than blowing their money on luxury goods, as the act of justifying expenses leads to higher resistance to impulse purchases.

Examples and case studies

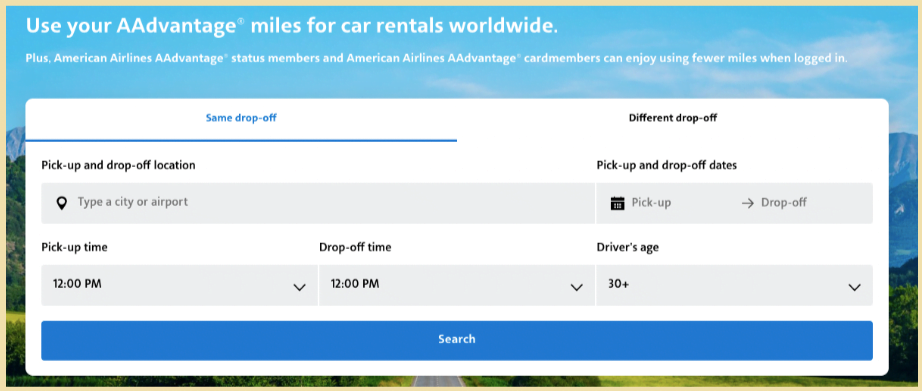

Taking the AAdvantage

If you are a frequent flyer, you will know the feeling of being bombarded by seemingly endless offers for redeeming free miles. The effort involved in getting them is virtually zero, as you receive them for trips you probably would have taken anyway. Yet you can exchange these points for meals, flights, suitcases, which are all (and here is the best part) free.

Source: American Airlines

Well not exactly. But thanks to mental accounting we feel like they are, and that is what matters.

American Airlines realized this and introduced their AAdvantage frequent flyer program in 1981. While it is essentially a customer loyalty program, there is a key difference. Research shows that discounts on services need to be large enough to be measured in percentages to sway a customer. Yet offering a discount of 3% or even 10% seems quite small when compared to the 20-50-70% discounts customers are used to in the retail industry.

To counteract this, American Airlines introduced AAdvantage. By shifting their rewards into a mile system, they led consumers to separate those miles from their monetary value and track them in separate mental accounts. When looking at their mile status, most people don’t see them as money, rather as an accumulation towards something free. And people love free.

Additionally, adding 1200 miles (one trip between Minneapolis to NYC) to your frequent flyer account will significantly increase your balance, while only costing the airline about $24! At approximately 2 cents per mile, frequent flyer miles are relatively cheap for companies, yet lead to greater customer loyalty, as getting thousands of points for a trip feels fantastic.

Mileage points also keep people loyal to an airline through providing “elite” status ranks. Besides carrying fancy names and stroking the passengers’ egos, the status also allows people exclusive privileges when flying with a specific airline (in exchange for points obviously). In some cases, they even motivate people to fly extra trips just to keep their status!

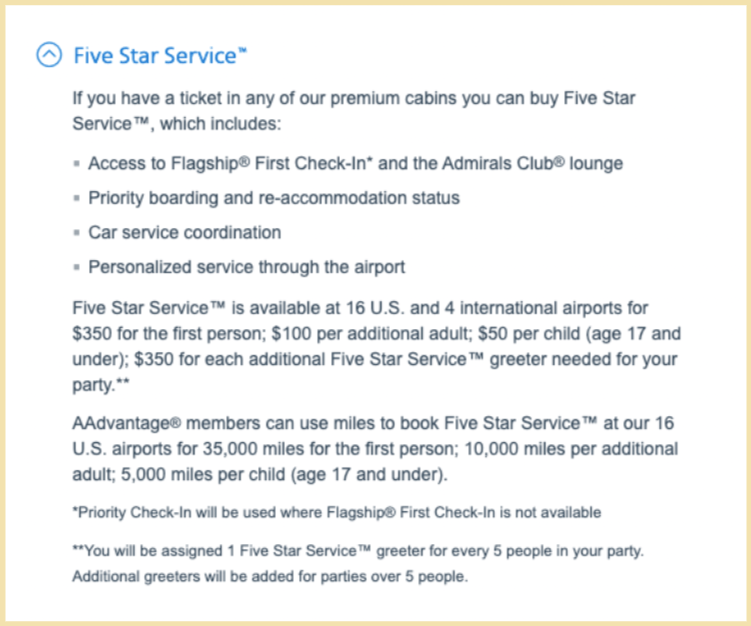

Source: American Airlines

The cherry on top?

Frequent flyer programs are financially viable! In 2019 American Airline reported $5.5 billion in loyalty program revenue, which is 12% of its total revenue.

Not just space capsules can skyrocket: Nespresso Capsules

As we earlier established, people judge an expense on its relative fairness. So Nespresso ran into a problem when looking to sell their new coffee machines to office buildings. Firms weren’t willing to pay a premium price for a then unknown coffee concept and sales started dwindling.

So, what did Nespresso do?

They changed the framing!

Instead of trying to sell their coffee to office buildings, they started an exclusive campaign to rebrand as a luxury home brand. They marketed their infamous Nespresso capsules as high-quality single espresso shots available at home. At the time, capsules were still relatively unknown and a novelty both in size and in pricing. That made the assignment of cost to a mental account ambiguous.

This allowed Nespresso to move the reference point for their capsules. Instead of comparing the capsule to standard home coffee machines, the natural reference point was where we normally consume and measure a single espresso coffee: cafés.

How much do you pay for a coffee from a café?

€2.50? €3? €4?

Suddenly, a Nespresso capsule, priced at 50 cents seems like an excellent deal, right?

Well actually, no.

At 50 cents per capsule, the equivalent price of a standard bag of coffee would be €45!

Luckily for Nespresso, most people, cognitively overloaded as they are, won’t calculate this price when buying capsules. Instead, they will leave with the feeling of satisfaction that they got a luxurious, café-worthy coffee for just 50 cents!

How does this relate to mental accounting?

Well, Nespresso understood that people evaluate expenses based on their reference prices. So by changing the reference price, they were able to move the comparison from grocery store prices to a premium level. Remember that Thaler said consumers care more about whether a transaction is perceived as fair than the actual price of the product!

Nespresso sustains this idea of luxury by maintaining their exclusive Club Nespresso and regularly releasing specialty café pods, marketing the exclusive coffee “lifestyle”. This makes the mental budgeting of Nespresso capsules even more ambiguous and allows the sale of a premium pricing model to consumers.

How can we use this in business?

Give out gift cards

A clever way to use mental accounting to your advantage is by offering gift cards or coupons.

Decision inertia is one of the biggest reasons for abandoned purchases and can be disadvantageous for both marketer and customer.

People are confronted with thousands of decisions every day, and for every single expense a budgeting decision has to be made. Decision inertia is one of the biggest reasons for abandoned purchases and can be disadvantageous for both marketer and customer. For instance, a customer seeking to buy a pair of new jeans might be overwhelmed by the sheer number of possible stores, styles and options available. This can lead to them abandoning the quest, despite being in dire need of new jeans.

A gift card can move this process along by essentially making the budgeting decision for the customer, so they don’t have to go through the cognitive pressure of doing so themselves. In addition, as we treat money emotionally rather than rationally, a gift card can evoke the principle of reciprocity and form a positive emotional bond with the brand.

This can be enhanced if a gain is offered in combination with a large loss, such as a “spend $200 now get $50 later”. In such a case, research has shown the occurrence of the phenomenon of double mental discounting.

Here consumers mentally deduct the value of the price promotion from the cost of the promotion-inducing original purchase, while also deducting it from the second purchase where the promotion is actually used. Through this “double-dipping”, a single gain, such as a gift card, can give customers the perception of costs which are lower than reality, thus triggering higher spending.

Ease the pain of paying

This is a big one: consumers feel uncomfortable when spending money. So, companies have to find a way to ease this discomfort in order to drive product sales.

People keep track of the depreciation of a product in designated mental accounts, where positive experiences accumulate to offset the original price paid for the item.

People keep track of the depreciation of a product in designated mental accounts, where positive experiences accumulate to offset the original price paid for the item. Only when the customer feels like they have got their money’s worth out of a product will they consider replacing or upgrading it. While this is beneficial to keep us from overspending, it can also mean that you hold onto a redundant item for too long when you might have been better selling it while it was newer and then buying a different product.

Companies can facilitate the break-even point, or simply ease the pain of paying too much for a product, by offering trade-ins. A recent study found that customers even prefer a trade-in to a discount!

Why?

The trade-in can give the old product one last purpose, thereby reducing the outstanding value difference between its price and accumulated enjoyment. This is perfect for individuals hating their original product but holding onto it in an effort to avoid the cognitive dissonance of disposing of it pre-emptively. As a result, this option is even more attractive than a straight discount, as you can focus on the benefit of getting a new product instead of the additional money spent on it!

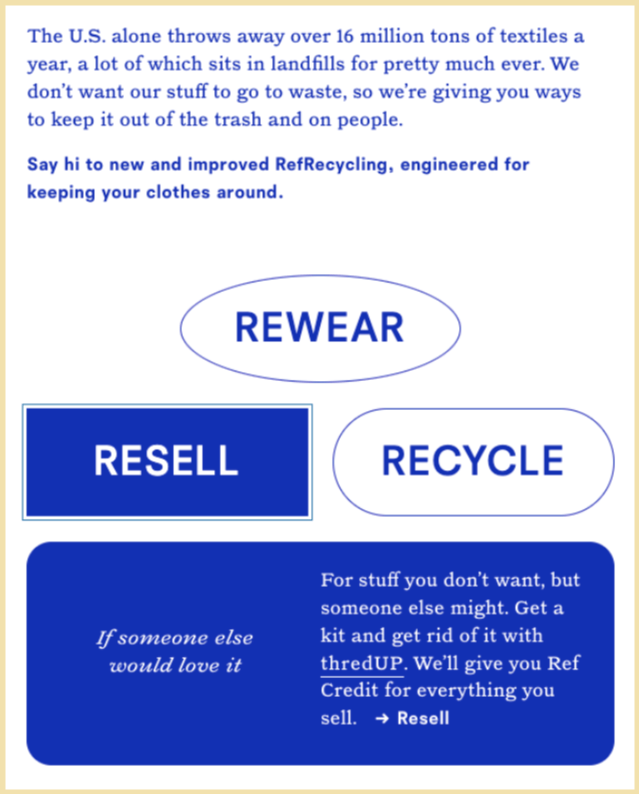

A great example of using this is Los-Angeles based brand Reformation. Check it out:

Source: Reformation

Their offer works well because customers get a trade-in credit in exchange for reselling or recycling their old clothes. This not only boosts customer retention, as the attained gift cards are brand-specific, but the commitment to sustainability and circular consumption also makes the brand more attractive to customers.

Separate payment and consumption

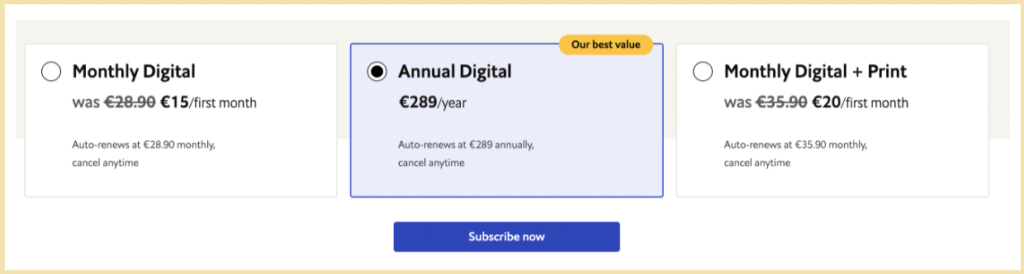

Separating consumption and payment has a significant effect on mental accounting. Our old friends Richard Thaler and Eldar Shafir found that paying for something long before using it can make the item feel like it was free when it is finally consumed.

Subscription services cleverly utilize this by offering a yearly subscription package at a great price. This way consumers perceive the access to the service as an investment in their personal enjoyment/development over the coming year. Additionally, instead of undertaking the recurring pain of paying monthly, they can rip off the band-aid in one go!

A great example of this is the American newspaper, The Economist. Check out their subscription offers:

Source: The Economist

Obviously, the most lucrative subscription format is the one in the middle, as it provides the newspaper with a large sum and alleviates the possibility of subscribers opting out during the year.

Can you also spot the clever ways, the Annual Digital option is made more salient?

If you need a little help, check out our articles on anchoring and decoys!

Make subscribers feel like that what they paid for is free.

Overall, by offering a yearly, or even sometimes two-year subscription, companies can achieve something magical. Make subscribers feel like that what they paid for is free.

People are forgetful creatures and aim to shake off negative experiences as soon as possible. That means they will attempt to mentally close the account of any subscription immediately, and will soon stop associating the product with its cost, leaving only the enjoyment of consuming it.

Demonstrate benefits, not just attributes

A great way to overcome prudent mental accounting and drive a purchase decision, is the separation of product attributes and benefits.

In most cases, consumers are overrun by alternatives to every product, with marginal differences in appearance. Just think about how fast faux designer bags and copycat designs arrive after the release of a popular new item!

But what can you do to stand out from the crowd?

Communicate value to your customer. If you have a great product, you should let the customer know exactly why it is great for them, instead of just listing its attributes.

Remember, in mental accounting purchases are weighted in price based on whether they are perceived as fair or being a great deal. The actual price of a product can be secondary. So, showcase the added value of your product, whether it is that your backpack is produced with spinal health in mind, or your shoe is approved by orthopedic doctors!

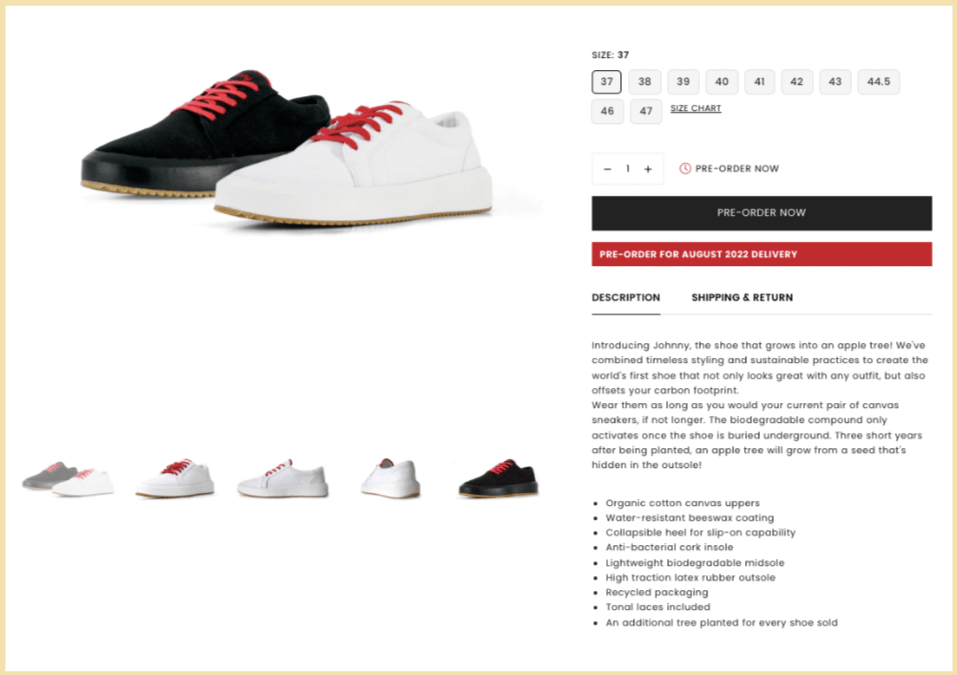

A great example of leveraging benefits of a product is the footwear brand Johnny. They were the first company to produce a fully biodegradable shoe, which offsets their carbon footprint and even grows into a tree if planted in the ground after usage!

They know the value of this benefit exactly and communicate it clearly on their website, in sync with the demonstration of their products’ attributes.

Source: Johnny Footwear

Important: be consistent across product pages on what the attributes/benefits are and keep the messaging short and sweet. Check out how Johnny emphasizes the benefits and attributes repeatedly on a new product page, in a concise and easily scannable way.

Source: Johnny Footwear

Don’t forget to test product badges to see what works! If possible, try and personalize messaging to your shopper to reflect their desires and needs. It might need some time, but if you can understand your customers, you can understand their mental accounting, and know how to highlight what is important to them in your product!

Summary

What is mental accounting?

Mental accounting is the process by which our brains try to keep track of money and regulate spending.

How/why does it work?

Mental accounting works through people assigning mental labels to money, deemed to help them oversee their financials and reach related decisions quicker. These labels are mostly arbitrary but carry some rationale in order to self-regulate. However, individuals seeking to indulge in desires, might adapt these budgets to their wishes, as they remain inherently malleable.

How can we avoid mental accounting?

You probably shouldn’t try to completely avoid mental accounting.

Instead focus on regulating and improving it. You can do that by capturing your budgeting in a written or digital format, and clearly marking/separating your important budgets from your remaining income. You should also take some time to think ahead, and consider the possible scenarios you might find yourself in. Come up with a plan for each, especially if it involves a large sum of money. You can also improve your self-control by making yourself accountable for your spending.

However, at the end of the day, remember we are not rational robots and there is nothing wrong with treating yourself from time to time. While you shouldn’t overindulge, don’t feel guilty for enjoying a premium experience from time to time, even if you could have deposited the money in your savings account instead.

How can you use mental accounting in business?

To overcome prudent mental accounting, you have to remember two important things:

- Ease the pain of paying

- Understand the mental accounting of your costumer

Aim to understand your business, from your customer’s perspective. Try to understand in which mental account your product could and what attributes can sway them into preferring it in this category. Examples of this can include handing out gift cards, offering trade-ins or even changing your payment plan. If running into trouble, you can always try to change mental accounts. Just think about where Nespresso go with the right communication and framing!

Overall, remember, mental accounting isn’t irrational, so be prepared to back up your product with a viable usage case!