The Decoy Effect – Everything You Need To Know

The Decoy Effect can bend others to your will, improve your health choices, and more! Here’s an essential guide on how to employ it to your advantage.

Article content:

The Decoy Effect defined

You might recognize it from fast food chains, coffee shops, or movie theaters. The Decoy Effect, also known as the attraction effect or the asymmetric dominance effect (if you want to sound extra fancy at cocktail parties), occurs when your preference for one of two options changes dramatically when a third, similar but less attractive option is added into the mix.

The Decoy Effect

Decoy is an option which no one is interested in because it’s objectively inferior to other options. It isn’t designed to be sold. Decoy has a different objective – to make other options seem more attractive.

The “decoy” is that third option.

It’s a pricing strategy that businesses use to get us to switch from one option to a more expensive or profitable one for them. By adding a decoy, they can influence what we choose without us even realizing. But the Decoy Effect is not just about prices, it can impact how we choose flights, soft drinks, or even potential romantic partners on dating apps.

Let’s explore what makes a good decoy, how it came to be, and what we can do to break free from its spell.

How does it work?

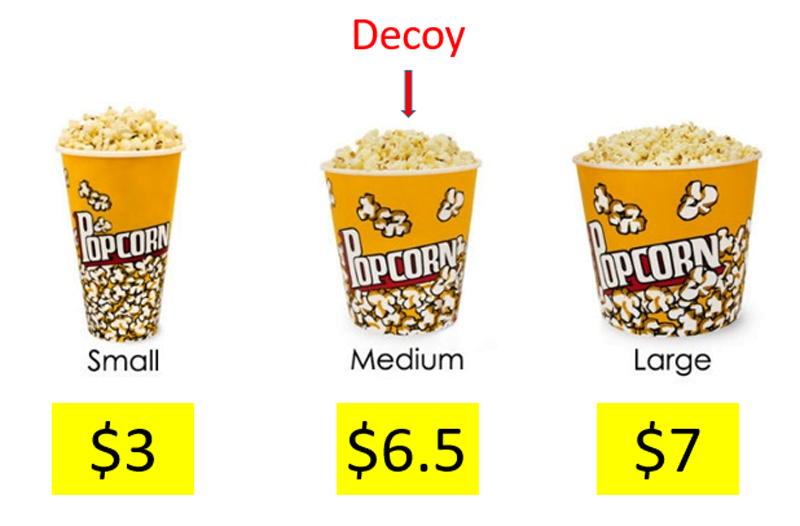

A decoy is the reason why the big menu feels like a bargain compared to the middle one or why you would get a large popcorn even though you swore you’d only get a small one. But then this is what you saw:

Source: Humanhow

Guess who’s swearing now – your wife whom you had promised you’d shake off vanity pounds! But it’s no wonder you chose the large popcorn since the difference in price between a small one and a medium one was $3.50 while the large one was only 50 cents more. What a steal!

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Your choice might have been different, however, if they only sold small and large-size popcorns; you might even have felt good about saving four bucks and your waistline.

Actually, this is not a random example, it was tested when National Geographic conducted the experiment on a bunch of unknowing moviegoers. Watch how it all played out:

Source: Youtube

Decoys change what we perceive as a good deal

To understand how decoys work, imagine you’re looking for a flight. When booking a ticket, we usually look for a happy medium between cost and convenience. Could adding a decoy change what option is viewed as more desirable and what trade-offs we’re willing to make?

Imagine you’re buying a ticket to Cancún and you have these options to choose from:

- Flight A costs $600 and has a 1h layover in Dallas

- Flight B costs $530 and has a 2.5h layover in Dallas

- Flight C costs $675 and has a 1h layover in Dallas (decoy option)

You and most people would choose Flight A, since it’s cheaper than Flight C, but with a shorter layover – even though it’s considerably more expensive than B. The presence of Flight C makes you feel like you’re getting a better deal at a better price.

Now consider a different scenario. Again, you’re flying to Cancún but you’re choosing from a different set of flights:

- Flight A costs $600 and has a 1h layover in Dallas

- Flight B costs $530 and has a 2,5h layover in Dallas

- Flight C costs $530 and has a 3,5h layover in Dallas (decoy option)

Why is Flight B more appealing now? At first glance this makes no sense: option B should be no more attractive now than in the first example because the waiting time and price are still exactly the same! But what has changed is Flight C. Its longer stopover has altered the way you perceive the other possibilities.

In both cases, Flight C is “the decoy” designed to appear similar to, but slightly less attractive than one of the other options (the “target”). And that comparison makes the target more appealing.

If you only saw Flights A and B, it would be hard to know exactly how to compare the trade-offs between price and waiting time. You might wonder whether an extra 90-minute wait is really worth it. But if one of the flights is clearly better than Flight C, on one of those measures, you have a ready-made reason to explain why you prefer it over the other.

Add a decoy and you can shift what feels like a good deal in a flash. As the first scenario goes to show, its mere presence can make you willing to shell out more cash. In fact, there’s evidence that a well-designed decoy can shift preference between the other two options by as much as 40%. Do it well and people won’t even realize that their decision-making is being manipulated, instead, they’ll feel like they’re making the logical choice.

Decoys help us to see value

Adding a decoy could even mean introducing an option no one will buy. Let’s say you want to buy a monthly membership to a sauna. You can choose from the following options:

- Option 1: For $120 a month, you can access the Traditional Finnish Sauna, Dry Cedar Sauna, Turkish Bath, and Infrared Sauna; or

- Option 2: For $75 a month, you’ll get access to 3 types of saunas except for the last one – the Infrared Sauna.

Which one would you choose?

Well, since infrared saunas are the latest type of sauna, you might not be sure whether it’s right for you, not to mention that the price for all 3 types of saunas that you’re already familiar with is nearly half. You aren’t sure how much an infrared sauna is really worth, anyway…So you’re happy to go with Option 2.

Guess who’s not happy? The sauna owner. Their intention is to sell what’s known as “the target” – Option 1.

What could they do to make you change your mind? Hand out a free coupon to try it first and eliminate the killer of all sales: uncertainty? Or, perhaps, provide a discount for a limited time to leverage the mother of all sales techniques: scarcity?

Yes, they could, but both of these options would cut down on their margins. Is there a way to achieve the same results without handing out discounts?

You bet there is: add the decoy.

- Option 3: For $119 a month, you’ll get access to just the Infrared Sauna.

“Hang on, that makes no sense,” you might think. No one is going to buy that. It costs nearly as much as Option 1 but doesn’t include the 3 most popular sauna types.

Okay, we hear you, but let’s go back to the decision-making stage for just a moment:

- Option 1: Monthly access to the Traditional Finnish Sauna, Dry Cedar Sauna, Turkish Bath, and Infrared sauna for $120

- Option 2: Monthly access to the Traditional Finnish Sauna, Dry Cedar Sauna, and Turkish Bath for $75

- Option 3: Monthly access to just the Infrared Sauna for $119.

Which option feels like the best value for your money now? Unless you are militantly against infrared saunas, you’d probably pick Option 1.

No discount, no trials. “Just” is an option that no one will buy and businesses know it. In fact, they are totally fine with it, its magic is that it changes what we perceive as the best deal, and as a result, we swap our preference between two options toward the target.

How exactly does it work?

We often think more options will lead to easier decisions. In reality, we get overwhelmed when we have too many alternatives and become anxious about making the “wrong” choice. As a result, it becomes harder to make any decisions at all.

A growing amount of research shows that when faced with a complex choice, it’s harder to make a decision. We experience choice overload, or what Barry Schwartz has described as “the tyranny of choice.”

The main problem is uncertainty. There are numerous factors we could take into account in order to make a decision; the less certain we are about which ones should be prioritized, the more difficult it is to choose (and the more anxious we get). That’s why we only focus on a couple of criteria (like price and quantity) to determine what’s the best bang for our buck.

We only focus on a couple of criteria (like price and quantity) to determine what’s the best bang for our buck.

As it turns out, we’re more averse to lower quality than we are to higher prices. And that’s where the decoy comes in! It exploits this human proclivity and pushes us towards an option that is of both higher quality and higher price while making us feel like we’re making a rational and informed decision.

Usually, we don’t even realize that decoys have any impact on our choices; whatever we ultimately choose, we believe that we’re doing so independently.

The Decoy Effect is largely invisible, and that’s what makes it so powerful.

It is essentially a nudge, which means it doesn’t provide large incentives to behave a certain way and doesn’t threaten some form of punishment if we don’t decide any particular way. But just because it’s there, we perceive these key choice attributes in a different way.

There is evidence that when we make decisions, our primary concern is not to pick the correct option. Instead, we seek to justify the outcome of a choice we’ve already made. Decoys make us feel comfortable about our choice because it gives us a ready-made justification for it.

Experiments with the Decoy Effect

From its inception in the early 80s, researchers can’t seem to get enough of it. Some of the decisions they looked into might seem trite (such as how we choose a restaurant), while others can be far more impactful – showing that a decoy might be used to encourage people to make healthier life choices.

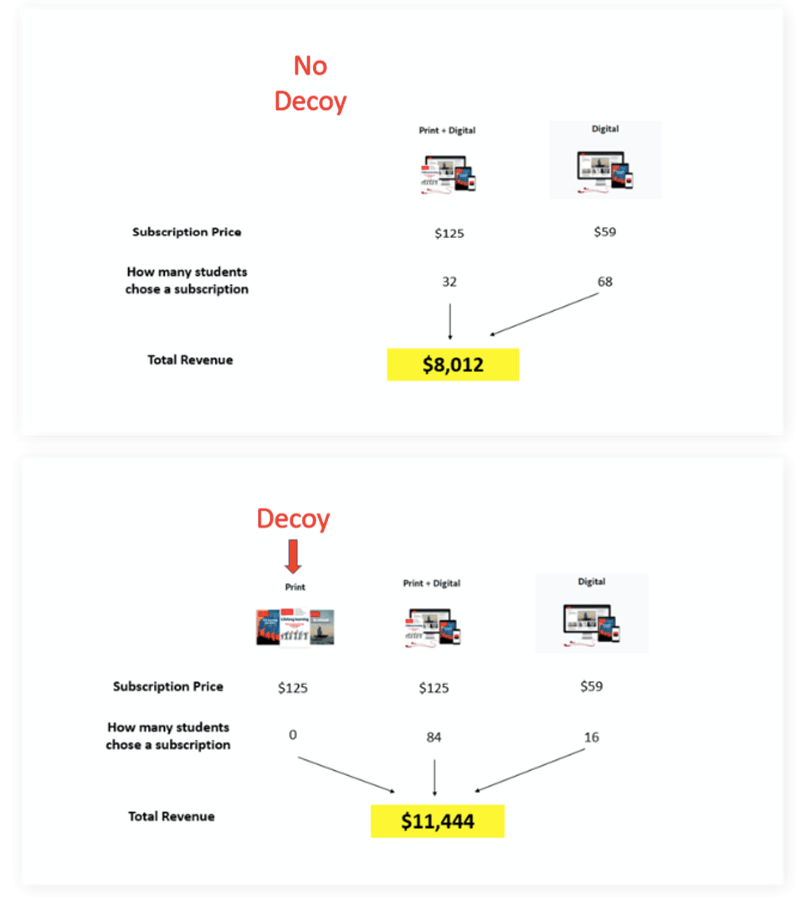

Newspaper subscriptions

The now-classic study was inspired by the real-life subscription model employed by The Economist in which they offered readers 3 subscription options: $59 for a digital subscription, $125 for a print-only subscription, and finally, $125 for both print and digital access.

Can you spot the decoy already?

Hint: it’s the one that offers less value for money. Yep, the unequivocally bad deal is print only. Dan Ariely was so intrigued by this model and whether it actually worked for pushing sales of the target option (i.e. print + digital access) that he tested it out on 100 MIT students.

First, he presented them with the three options and asked them to pick one. 16% of the students chose the cheaper online subscription, 84% chose the print & web subscription, and nobody chose the $125 print-only subscription.

Then he removed the $125 print subscription, the option nobody picked (as any rational person would do), and asked a different group of students to pick from the remaining two. This time, 68% picked the $59 online subscription, and only 32% picked the print & web subscription.

Source: Decoy Ebook

And voilá, to quote maestro Ariely himself: “The most popular option became the least popular, and the least popular became the most popular.”

To hear more about how Ariely describes other experiments that he’s conducted with regard to the Decoy Effect, skip to the 11-minute mark. A little teaser: it has to do with choosing your vacation spots.

Source: http://www.ted.com

Even though students would be perfectly content with digital-only, adding a decoy made them appreciate the value of it and nudged them to spend almost $70 more on something they didn’t really need.

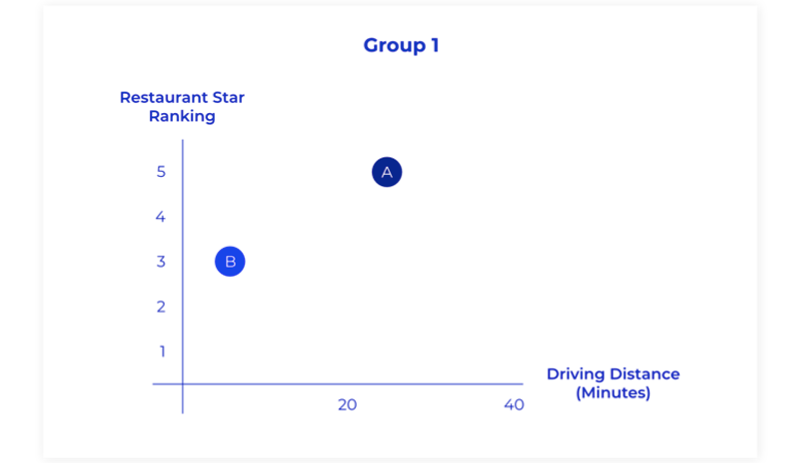

Restaurant preference

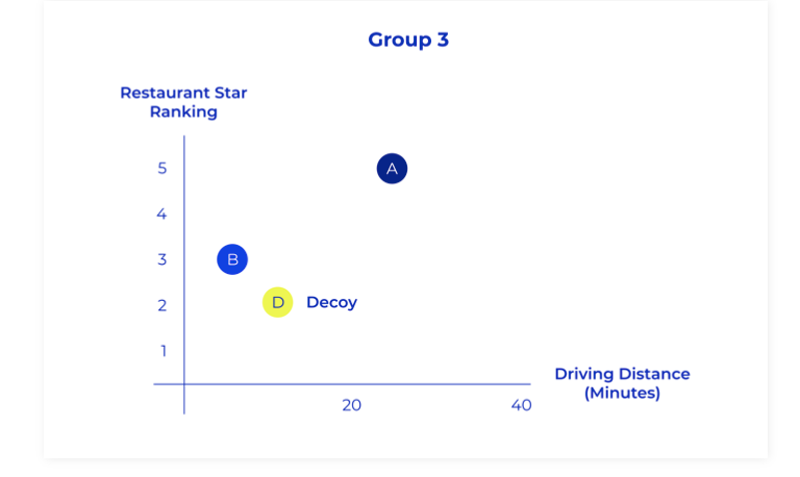

Another study set out to explore how the Decoy Effect impacts our everyday decisions; what trade-offs we’re willing to make and how these change based on a decoy. In this case, the two key criteria on which people were asked to base their decisions were quality and convenience.

The first group was asked to choose between:

- A. a five-star restaurant that was a 25-minute drive away,

- B. a three-star restaurant that was a 5-minute drive away.

In this setup, there is no decoy that might otherwise help establish quickly which one is the no-brainer option. The extent to which someone might prioritize quality over convenience is largely dependent on who you ask. For example, an avid driver and foodie wouldn’t mind taking a drive to a five-star restaurant while someone with a less defined palate would opt for the shorter drive and more average meal.

Source: Decoy Ebook

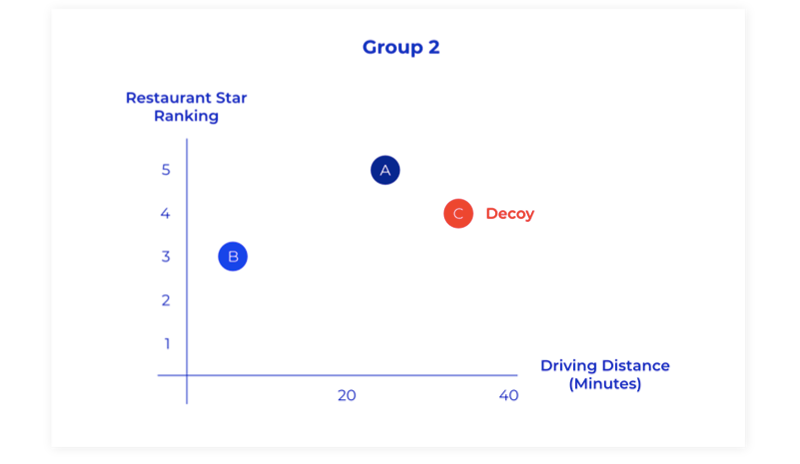

The second group was given options A and B plus a decoy option

- C. a four-star restaurant that was a 35-minute drive away.

The target (the option the researcher wanted more people to opt-in) was the fancy, 5-star restaurant within a 25-minute drive.

Source: Decoy Ebook

And it worked! In this setup, most people chose Option A: the five-star restaurant. The decoy, Option C (which scored lower on both quality and convenience), when compared to Option A made Option A look more attractive and directed people’s attention to it.

Perhaps you can guess what’s next. Yes, designing a decoy for Option B – which now becomes a target.

Take a minute to think about what it could look like. Hint: It has to be inferior to B (a three-star restaurant, a 5-minute drive away) in both the quality of food and driving distance.

Now check if you got it right. Option D: a two-star restaurant that’s a 15-minute drive away.

Source: Decoy Ebook

Now, the majority of people went for option B, the 3-star restaurant. The Decoy Effect of Restaurant D caused people to direct more attention to the driving distance, whereas in the second group, Option C provided justification to drive a little bit further for quality food.

Colonoscopy appointments

Scientists in the UK have also started looking into whether decoys could be used to influence life-or-death choices. Christian Von Wagner’s team looked into whether adding a decoy might encourage more people to undergo a vital but unpleasant procedure – a colonoscopy that screens for colorectal cancer.

The presence of a decoy simply made the screening at the “target” hospital appear less burdensome.

The fact of the matter is that when people are given a choice between scheduling an appointment or not, many choose not to. But Von Wanger has found that if a third option was present – an appointment at a less convenient hospital with a longer wait time (similar to the restaurant example) – more people were willing to book an appointment at the ”target” hospital.

The presence of a decoy simply made the screening at the “target” hospital appear less burdensome.

A History of the Decoy Effect

Like many of the now-infamous cognitive biases, the Decoy Effect is a millennial – first documented in the early 1980s.

In fact, the Decoy Effect is a bit of a troublemaker as its birth caused quite a stir! It was long believed that no such effect could exist because it violates the regularity principle – the notion that if we add a new option to a set of existing options it could never increase the likelihood of choosing a member of the original set (the target). Psychologists and economists believe that this new option would in fact cannibalize the market share of existing options.

But in 1981, academics Joel Huber, John Payne, and Christopher Puto ran a series of experiments showing that a decoy acted more like a best friend in a rom-com. It supports and shines the limelight on the main lead and can, in fact, boost the lead’s popularity.

Where researchers asked participants to choose between a number of hypothetical alternatives ranging from beer, cars, restaurants, lottery tickets, camera film, and television sets, each scenario (except the one involving lottery tickets) showed that the presence of a decoy increased people’s preference for the target option.

How to avoid it

What makes the Decoy Effect especially tricky is that just because you know it exists, it doesn’t mean you can always spot it. Afterall, the part of what makes it so appealing is that our choices under its influence feel rational. And you can’t even rely on a group to set your thinking straight either, as it was found the Decoy Effect affects group decision-making as well.

When making purchasing decisions

Don’t decide based on your gut feeling

The good news is that not everyone is equally susceptible to decoys. If you’re a more analytical type and prefer deliberative reasoning, you have a higher chance of avoiding it. But alas, if you’re more intuitive and rely more heavily on gut feelings, you might be more susceptible to the Decoy Effect.

Not sure which one you are? Simply ask yourself questions about how you normally solve problems. Do you believe in trusting hunches? Do you avoid thinking in-depth about problems? If your answer to similar questions is “yes,” chances are you’re an intuitive thinker. Here’s a demo of a full test.

If you’re a male who identifies as the analytical type and just breathed a sigh of relief, you’re not off the hook entirely. Hormones play a part too – the higher levels of testosterone that tend to make people more impulsive also means they are more likely to be swayed by its charm.

Get suspicious about a set of 3 choices

The Decoy Effect works best when you’re asked to choose from a set of three options. So whenever you spot a set of three options, approach it with a lot more scrutiny to see whether you can spot the decoy.

Define your deciding factors ahead of time

When you aren’t clear on what attributes matter to you most, you’re more likely to fall for the Decoy Effect. Figuring out what parameters you value the most might offer you some protection. Before browsing your options, make sure you’re clear on what factors you’re unwilling to budge on.

If you’re shopping for a plane ticket, is it the layover time or the cost of the flight that matters? Chances are that if you revisit the attributes you were originally seeking, you might spot you are about to compromise on them. If that’s the case it is possible you are being distracted by a deliberately unappealing alternative.

Ask: Do I have use for it?

Perfume manufacturers are superb at using decoys. Just one example of many is Jo Malone, which prices its Wood Sage and Sea Salt 100 ml cologne at $145, 50 ml at $100, and 30 ml at $75.

If you do all the calculations in your head, you’ll see that the medium-size option is a better deal than the small-size option and that the large-size option is an even better deal. Since the medium price is a nice, rounded number (not $98.99), you can quickly calculate that you “save” 55 dollars if you opt for the large-size option instead of the medium-size one.

But does buying a 100ml bottle really fit your lifestyle needs? And if it doesn’t, is it still the best deal? If you like using just one fragrance at a time and you basically bathe in it, then definitely.

Next time when your gut feeling is to make a “sensible choice”, just pause and think about whether it really is the best fit for you, or whether you're just being manipulated to spend more on a perfume that you will eventually have to throw out anyway.

But if you like to switch between several fragrances depending on your mood, or don’t use it that often (and have had to dispose of some fragrances in the past as they got too old and started smelling a bit funky), then you might have just lost money by buying the large-size option.

So next time when your gut feeling is to make a “sensible choice”, just pause and think about whether it really is the best fit for you, or whether you’re just being manipulated to spend more on a perfume that you will eventually have to throw out anyway.

When evaluating others

Be aware that decoys reach far beyond your consumer decisions. As it turns out, the way we evaluate others – as more or less valuable – depends on the context of other people.

If you come across two similar candidates, with one being slightly superior to the other, it will heighten your regard for them compared to the other more “different” candidates.

Dan Ariely’s research shows people are more likely to fancy someone more if they appear alongside a “decoy” who is similar looking, but slightly less attractive. Something to be mindful of if you are flicking through profiles on Tinder or Bumble – the specific sequence of profile pictures on dating apps can influence who you swipe right with and whom you pass on.

The same is true for hiring, Linda’s Chang research has found that people’s preferences between two candidates may shift if the recruitment process also includes a third “decoy” candidate.

Although the “decoy” in these circumstances may be accidental rather than deliberate, if you come across two similar candidates, with one being slightly superior to the other, it will heighten your regard for them compared to the other more “different” candidates.

Examples and case studies of the Decoy Effect

IKEA’s “backoff” range

Did you know that the Swedish furniture retail company has a line of specific products which serve as decoys? They range from beds, chairs, and nightstands to chests of drawers…

For instance, there’s a specific chest of drawers that the company really wants to push forward for a high-profit margin. And then there are those that don’t meet to sell and that’s fine.

Meet KULLEN and MALM. Can you guess which is which?

Source: Author’s Archive

The KULLEN is a low-profit-margin product that IKEA doesn’t intend to sell. It has a similar design to the MALM on the right, except it’s smaller, made out of inferior-quality wood, and has fewer drawers that don’t open as smoothly.

At store locations, the €39.99 KULLEN is displayed right next to the MALM, which is more expensive and goes for €59.90. But it doesn’t matter because it’s a much better value for your money. Customers can see it with their own two eyes. The decision? It’s a no-brainer.

As you can see, the KULLEN isn’t a waste of resources, as it alters the decision-making context and sways people toward the more profitable option. This works because customers don’t know how much things or products should cost.

Creating a decoy gives people a sense of value, and making comparisons helps them to assess quickly whether something is a good deal or a pass.

Read more about why this is a great strategy to decrease choice overload.

Apple’s iPod “Goldilocks Effect”

Apple designs its product selection to leverage both the decoy and the Goldilocks Effect (also known as Middle-Option Bias), which is the human tendency to gravitate towards the median, “just-right” option.

The Middle Option

The middle option, also known as the centre stage effect, is our tendency to choose options in the middle. It works best if the differences between the options are simple and clearly communicated.

Notice Apple doesn’t push its customers towards the most expensive option. Instead, they leverage a pricing strategy that involves three options: one that’s too high for most, one that’s too low for most, and one that’s just right.

See if you can spot them in the pricing of its iPod from 2013:

- 16GB for $229 – without 5MP iSight camera and iPod Touch Loop

- 32GB for $299 – with 5MP iSight camera and iPod Touch Loop

- 64GB for $399 – with 5MP iSight camera and iPod Touch Loop

As you can see with each upgrade, there is a series of trade-offs to make. But thanks to decoys, (yes, there are two) these trade-offs are not valued in the same way.

If you opt for the middle option: 32GB for an additional $70; you get double the storage capacity and also get more features, such as a 5MP iSight camera and iPod Touch Loop.

However, if you opt for double the capacity (from 32GB to 64GB), you pay an additional $100, but you don’t get any extra features.

Thus this pricing model makes an upgrade from 16 to 32GB feel like a sensible decision, while the other (from 32GB to 64GB) feels not so justified. And so, most customers conclude the 32GB iPod offers the best value for money.

Only a few would buy the 16GB version and even fewer would opt for the 64GB version.

But Apple isn’t bothered, the truth is both 16GB and the 64GB versions are the decoys designed to make the 32GB version more appealing. Apple also uses this strategy for higher-priced products, such as its MacBook Pro.

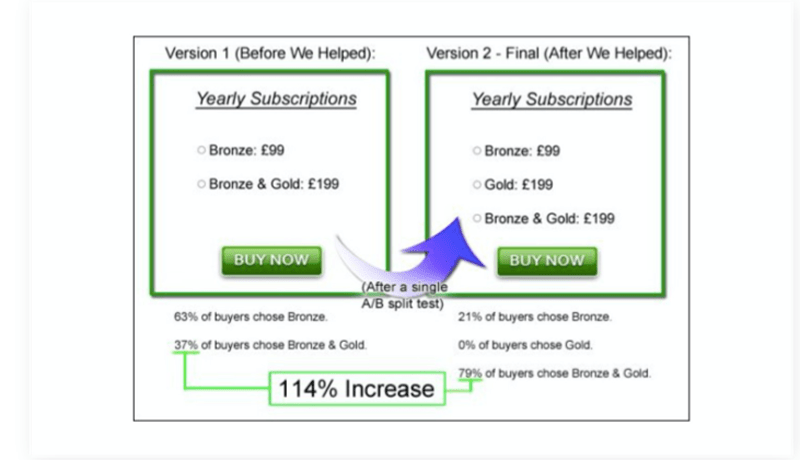

SaaS subscription

Another interesting example is yet again related to subscriptions. In this case, A/B testing was used to measure the Decoy Effect. You can see that before introducing the Gold decoy option, only 37% of all customers picked the most expensive option.

However, after the Gold option was added, 79% opted for the most expensive Bronze & Gold form of subscription.

An impressive increase of 114%, which was made possible without having to decrease the price for the most expensive option.

Source: Decoy Ebook

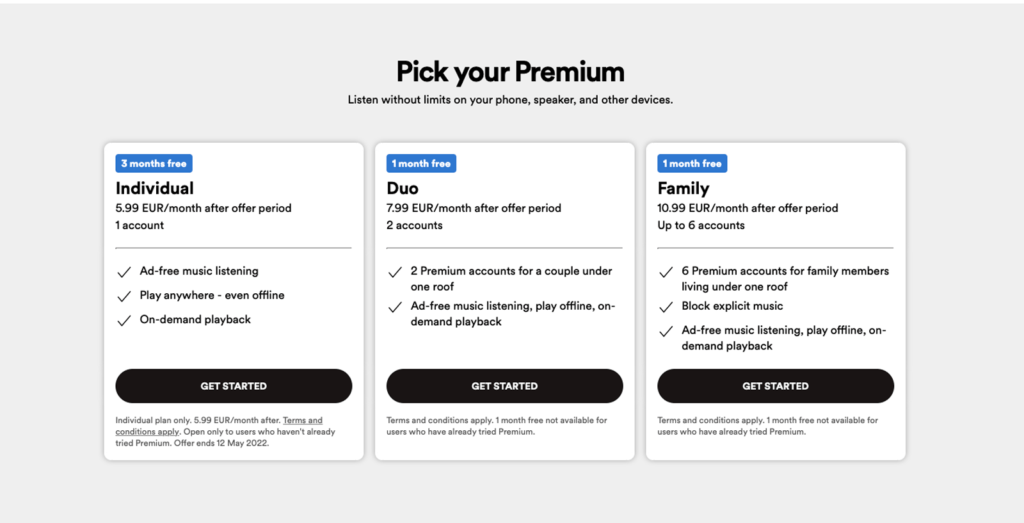

Spotify’s Individual Plan

Spotify makes the Family Plan seem like the most preferable option. And even if you have no use for a family account, if you’re a young couple, still opting for anything but the Individual Plan feels like a good call. The Individual Plan serves as a reference point for you to weigh the two other options. Without it, you wouldn’t be able to appreciate how good of a deal you’re getting if you opt for any of the two remaining options.

Source: Spotify

How to use the Decoy Effect in your business?

We encourage you to try this at home as long as you keep the following in mind:

1. Pick a target option – the product you want to push forward

A good candidate for a target is the product or service that already contains more benefits, is priced higher than the other products, or has a higher margin.

With that being said, just bear in mind that a decoy is not a panacea. Customers must already like the target! If you have a bad product, or if there’s no product-market fit, introducing its inferior version might not be enough. People will still not find it valuable enough to buy.

2. Introduce a subtle decoy

The rule of thumb is that a decoy should offer less for almost as much money. Price the decoy close to the target product and make sure it doesn’t offer as much value as the target – which means that opting for a more expensive target would still feel like a better deal.

Price the decoy close to the target product and make sure it doesn’t offer as much value as the target.

The beauty of decoy is that it is subtle; if you go overboard with pricing, customers might “catch on” to what you’re trying to do. So if you want to keep the decoy price still favorable (relative to the target), but overall less appealing, you can introduce a new feature.

This new feature must be something totally irrelevant to the core product features. But at the same time, it must be something that can be used as a justification to the consumer. The most common example is by offering a strange color, like orange, that nobody wants in the first place.

Apple used a similar strategy back in 2013 when they set the price of its not-so stylish and “plastic-looking” iPhone 5C (remember those?!) higher than what the price for comparable phones from different brands was at the time.

Some people bought the 5C (not such a perfect decoy after all), but most people opted for the more expensive 5S. In this setup, paying an extra £80, for an aluminum golden edition compared to a green, plastic one didn’t seem like such a bad idea.

3. Make sure the deal contains a third option that’s different than the target.

You need to have at least three options. Any more than that might increase your chances of choice overload and lead to decision paralysis.

Summary

What is the Decoy Effect?

It’s a pricing strategy that businesses use to get us to switch from one option to a more expensive or profitable one for them.

The Decoy Effect occurs when the preference for one of two options changes dramatically after a third similar but less attractive option is added.

The “decoy” is that third option. By adding a decoy, you can influence what customers value – they will feel like they’re simply making the logical choice. It’s because a comparison with the decoy offers us an easy justification for an otherwise arbitrary decision.

How to avoid the Decoy Effect for yourself?

Remember that what might feel like the most sensible choice might not be the most sensible choice in your personal context.

Scrutinize “a sensible choice.” How much value does it bring to you? Is it in line with your goals or behavior? Yes, a large soda or family pack of cookies might be the best value for money, but it will actually set you back on your weight-loss goal.

If you’re shopping for a product or service, it always helps to define your decision-making criteria ahead of time and then explore if they’ve suddenly shifted. You might find that you’re just having a knee-jerk reaction to a clever decoy.

If you’re purchasing a product with a limited lifespan, also ask yourself how often would you use it? If you stick to what’s sensible for your lifestyle needs, you might avoid throwing away half-used, large-sized creams or perfumes.

If you’re evaluating people in hiring or dating situations, just be aware that you might be judging someone while still “under the influence” of someone else.

How to use the Decoy Effect in business?

When coming up with a decoy, think beyond prices. The decision might very well be quality versus convenience.

The main objective of a decoy is to help create the sense that your target product is a good deal – either by changing the relative value of different parameters (cost vs. layover time in case of a plane ticket) or by the classic, more-for-less approach (perfume sizes).

A quick guide to creating a decoy:

- Pick your target – i.e. the product or service you want to push forward. Remember it has to be something customers already like.

- Introduce a decoy. The rule of thumb is that it should offer less for almost or exactly as much money. A very bad deal in context. The decoy isn’t supposed to sell, only to change the context. Don’t go overboard if you still want to make the price favorable, you can make a decoy less appealing by modifying a different feature such as a color.

- Make sure to include a third option that is different from the target and decoy.