The Endowment Effect – Everything You Need to Know

The endowment effect is one of the most important biases out there and it affects you daily. Here’s everything you need to know about it.

Article content:

Definition of the endowment effect

According to behavioral economics and psychology, the endowment effect occurs when we attribute greater value to things we own than to things we don’t. We overestimate their real market value and as a result, we demand much more to give these things up than we would be willing to pay to acquire them.

What is more, we don’t need to even actually own the thing. It just needs to feel like we do. This is called psychological ownership, or quasi-ownership.

How does the endowment effect work?

The answer is sentiment. We feel a sense of ownership and possession. These things are ours; we’ve been through a lot with them and made a lot of nice memories. We just don’t want to let them go.

Just think about the old, ragged, and to be honest, slightly smelly university hoodie you got in your freshman year. It drives your partner crazy constantly, but you just love it. Think about the 20-year-old car that has sat unused in your grandpa’s garage for the last 10 years. He couldn’t sell it just like that, could he?

It gets even more interesting. Imagine someone wants to buy that hoodie from you, let’s say, for 10 bucks. Seems like a fair price? Absolutely not! The hoodie is full of happy memories, it’s $40, at least, you think. And so, you reject the offer. This is so-called opportunity cost – the benefits you miss out on because you refuse good deals.

Now imagine you see a similar, torn, stained hoodie at a local thrift shop with a $40 tag. You probably wouldn’t think the same way then. Who in their right mind would pay $40 for that?

By the way, that’s exactly why retailers, even online retailers, let you try their product before you buy it. That’s the psychological ownership mentioned above.

When you try on new clothes or start your Spotify Premium free trial, you feel what it’s like to own them. And it’s very hard to let that idea go.

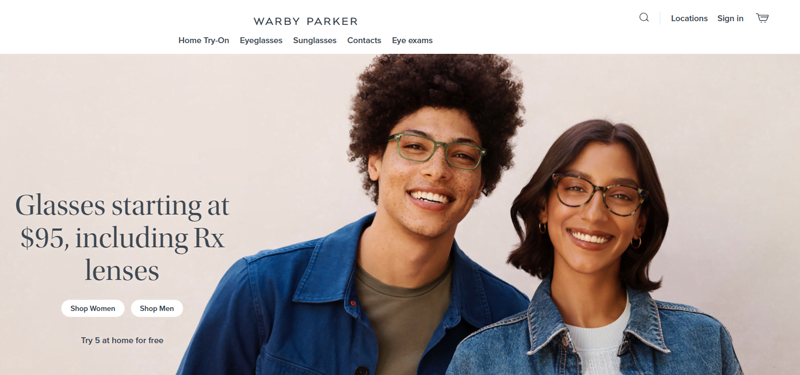

For example, the eyeglasses eshop Warby Parker allows their clients to order up to 5 frames, try them on, return those they don’t like, and only pay for the ones they intend to keep.

The thing is, once you try them out and take them for a walk to test them with your favorite outfit, you feel like you own them already. Sending them back suddenly becomes pretty difficult.

Source: Warby Parker

It’s not like trying products is a bad thing – you should certainly try things before you buy them. However, be aware that that feeling of ownership will inevitably come along.

Why does it work?

Loss Aversion

We are roughly 2.5 times more sensitive to losses than we are to gains of similar size. A message framed as a potential loss might therefore be more persuasive.

The endowment effect is based on one of the most powerful cognitive biases out there – loss aversion. To put it simply, we hate experiencing losses about twice as much as we like experiencing gains. In other words, you would be twice as sad if you lost $20 as you would be happy if you found the same amount.

Because of that, we make biased decisions as we focus more on what we can lose than on what we can gain.

This loss aversion sets the stage for the endowment effect. As we don’t like losing things, we attribute more value to them to cover for their loss. And it also works the other way around – neuropsychological studies show that once we own something, the possibility of losing it is even more salient.

Endowment effect experiments

The endowment effect has a strong scientific basis with dozens of experiments proving it again and again. Let’s go through some of them.

Mugs

One of the most famous experiments confirming the endowment effect comes from Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler. They offered participants mugs and then allowed them to sell them or trade them for equally priced pens.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

And what did they find? To compensate for the mug, the owners asked approximately twice as much as they were willing to pay to acquire the mugs!

The owners ask approximately twice as much as they are willing to pay.

Lottery tickets

A similar one comes from the ‘80s. The participants in this study were gifted with either a lottery ticket or $2.00.

Later, each of them was offered an opportunity to trade the lottery ticket for the money or vice versa. Very few subjects chose to do it. Those who were given lottery tickets seemed to value them more than the $2.

Basketball tickets

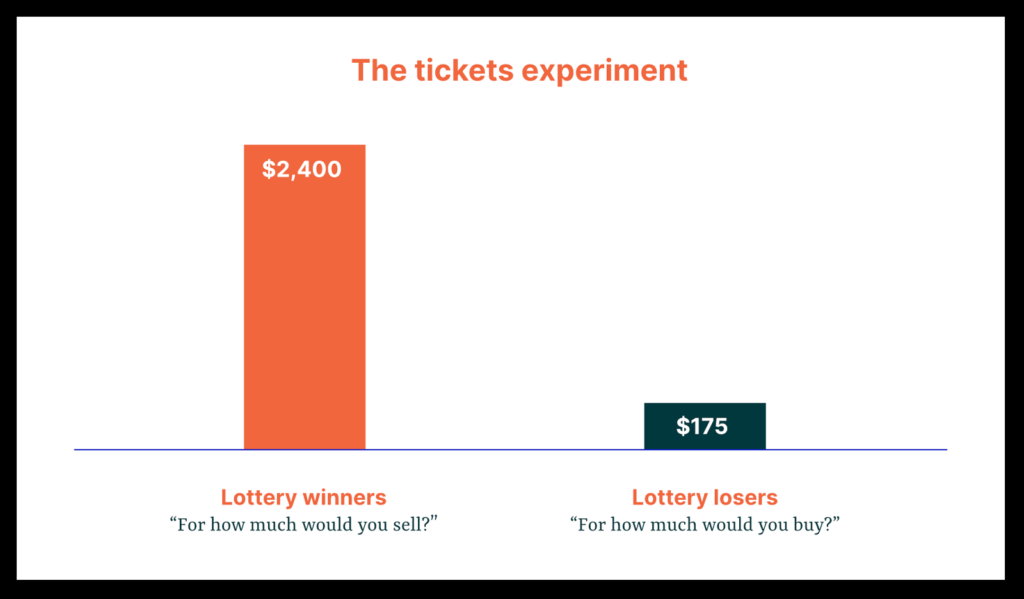

The last study on the list is a classic. Dan Ariely and Ziv Carmon from Duke University examined the endowment effect under real-life conditions. The most popular sport at Duke is definitely basketball. There is literally not enough space for all the people who want to get into games. That’s why there’s a lottery with a ticket to a game as a prize.

After the lottery, Ariely and Carmon asked the ticket winners how much they would be willing to sell their tickets for. The losers, on the other hand, were asked how much they would be willing to buy the ticket for.

Perhaps it’s not that surprising that the losers were willing to pay $175 per ticket. But the winners? They wanted $2,400 on average to sell!

Source: InsideBE

History of the endowment effect

If you think history is boring, how could it be that the discovery of the endowment effect is associated with not one, but two Nobel prizes? Yes. you read that right. Let’s see how that happened.

It’s 1979. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky had just observed a really weird thing. The results of their study showed that people reacted to risky situations very differently than the models of rational behavior predicted. When faced with the possibility of losing, people were willing to risk much more than when facing a chance to gain, just to avoid the loss.

The core assumption that the authors came up with was loss aversion – the basis of the endowment effect. The numbers were clear, so they published their new theory called the Prospect theory. Nowadays, it’s known as an absolute cornerstone of behavioral economics.

Over the years, it turned out that this new model of Kahneman and Tversky explained human behavior much better than classical theories of rational behavior. But first and foremost, it was a huge help for economists to understand how people think about their finances.

One thing led to another and Kahneman was awarded the Nobel prize for economics in 2002. Unfortunately, Tversky had passed away six years earlier, so couldn’t share the award.

But it doesn’t end there. People were digging deeper and deeper into the Prospect theory. One fairly unknown economist at that time, Richard Thaler, was interested in why the heck people made such irrational choices. Why are they so afraid of losing things?

He was aware that such behavior can be really cost them. The fear of losing prevented people from making good deals. In other words, they fell prey to the opportunity cost mentioned earlier. And that was simply because they attributed an irrationally high value to the things they endowed. He was the first one who coined the term Endowment effect.

Thaler was a huge contributor to the field of behavioral economics, thanks to his work on the endowment effect and financial decision making overall. In 2017, he was awarded the Nobel prize in economics.

How to avoid the endowment effect?

Biases like the endowment effect are tricky, as they have evolved over millions of years. There is no guaranteed way to get rid of them. However, you can try to be aware of its influence and make a rational choice instead. Here’s a little help with fighting it.

Fighting the endowment effect as a seller

For sellers, opportunity cost is a real threat. Here’s how you avoid it:

- Studies suggest you should do your market research. You are not the only one selling this stuff, whether it’s a car, old books or clothes. You’ll find a range of prices that this item is usually sold for. Try to stay closer to the middle of that range.

- Ask yourself, how much would you be willing to spend if someone else offered you a similar product?

- How many deals have you already rejected? If it happens that dozens of potential customers offered you a lower price, maybe it’s not them. You might be missing out on good deals here.

Fighting the endowment effect as a buyer

If you’re in the market for a product, here’s what to look for:

- Free trials and try-ons are red flags. Whenever some company offers you the opportunity to try their services for free or is very explicit about how they will let you try multiple products for days or months free of charge, be aware.

Again, you should definitely try before you buy. Just know that sellers are very intentional about creating a sense of ownership - Sellers want you to imagine a situation vividly. They describe very realistic situations that you can relate to very easily about the problems you might be facing. For example, a company selling pillows may portray you having the best sleep ever, asking you when the last time you experienced that was. A long time ago? Well, imagine how it would feel to sleep like that every night. And then comes the part describing how great their pillows are. Bam! The psychological ownership is in play.

If you just don’t want to let your old stuff go…

If you are not a buyer or seller but your partner constantly complains that your old stuff just makes her/his life unbearable, here’s what to ask yourself:

- What value does this thing provide me? How much do you really need this item? If the answer is zero value, it takes up space, but I love it anyway, perhaps it’s time to say goodbye.

- How often do I use this thing? Daily? Weekly? If the answer is more like once or twice a year, or even less, it’s really not that necessary to have it around.

Case studies

IKEA’s secret of familiar homes

IKEA is one of the companies that has mastered the endowment effect on multiple levels. For starters, IKEA encourages its customers to try their products – to lay on their beds, to touch everything, to walk through the well-arranged rooms that feel like home. You can see their products in the context of a home – how they could actually look in your apartment.

That alone is enough to induce a feeling of psychological ownership. However, it doesn’t end there at all. When you walk into any of the rooms, it feels like you’ve just strayed into someone’s house. There are books on the shelves, shoes, and clothes in the closet, even perfumes and bottles of alcohol.

Each room is sized based on regional averages, and if there’s a balcony or a window, the view reflects that country’s landscape. Every one of these details completes a very specific image in customers’ heads and a very familiar feeling of home. It’s no wonder that we feel like we already own the items.

Uber makes customers feel like a discount is already theirs

Uber uses the endowment effect fairly easily when offering customers discounts – a simple change in wording is enough. Check the message that our colleague received recently.

Check the last paragraph – the promotion has already been added to your account. It’s already yours, so it would be a real shame not to use it, right?

They could have simply offered our colleague a discount with a phrase like ‘You can save up to 30%!’ But they didn’t. Instead, she felt like she owned the discount, and not using it would mean losing it.

Test-driving a new car

Have you ever purchased a new car? If so, you certainly know the drill of test driving. The car looks good on paper, it has all the features and specs you wish for, the color is cool, it even has a voice assistant.

However, nothing compares to the feeling you have behind the wheel. The feeling you get when turning the key and first feeling the engine roar … the goosebumps you get when you first try to accelerate … how great it holds the road.

It’s a classic sales tactic and it works like a charm, precisely because of the endowment effect. It’s not just about trying: it’s about imagining that this could be your daily drill. Screw the paper specs, you just want the car even more now.

Bang & Olufsen – see, how the product will fit your home

Bang & Olufsen takes the endowment effect seriously. They have even transferred the whole try-on experience to the online space. They allow customers to move, build, and manipulate their product. They can see it from all sides, from all angles.

This way, customers get a very clear image of not only how the product really looks, but mainly, how it will fit in their home.

How to use the endowment effect in business?

For many businesses, creating a sense of psychological ownership is the way to go. Usually, it doesn’t take much to make your customers act like Gollum, who won’t let his precious go. There are 3 basic ways to leverage it:

1. Let your customers imagine they already own your product

When selling online, it might seem a bit difficult to make customers feel like they own the product. But it’s not. What you need to do is to put the idea in their heads and make them picture as vividly as possible what life with your product would feel like.

It can be difficult for customers to imagine what they will end up getting and how it can improve their lives. But with specific information in mind, it’s much easier. Airbnb is a good example.

Let’s say you’re a homeowner and you’re about to take a long holiday abroad. Is there anything you could do with your place in the meantime? How about renting it? But… why should you? What’s in it for you? It can be difficult to imagine if you’ve never done it before.

In this case, Airbnb rose to the challenge and told homeowners exactly what amount they could earn:

Source: Airbnb

Airbnb put a very specific idea in people’s heads. But they could have pushed it even further if they had asked the homeowners:

“How would you use an extra €2,564?”

And let me tell you, it’s easy to envision what to do with almost €2600! Asking questions triggers people’s imagination very well and mixing it with the endowment effect is a good recipe for creating psychological ownership.

2. Make customers feel like a discount is already theirs

Remember the Uber example from above? Yes, that’s a good way of presenting discounts. Don’t say to customers that they can earn it, or that it’s within reach. Tell them, it’s already theirs, waiting to be used.

Don't say to customers that they can earn it, or that it's within reach. Tell them, it's already theirs, waiting to be used.

One of MINDWORX’s case studies describes the consultancy’s collaboration with a telco operator. MINDWORX was asked to get more of the company’s customers to activate a package of free mobile data.

The only available channel was SMS. To activate the offer, customers needed to answer YES to the text message. The original CTA went like this:

“Answer YES and we’ll activate the package for you”

MINDWORX replaced it with a clever CTA inducing endowment:

“We’ve given you a mobile data package for free, it’s ready to be used. Just answer YES to activate it.”

It worked like magic. All it takes is a knowledge of behavioral economics and a handy copywriter.

3. Let customers try the product

If you have an option to let your customers try your product, do it. Nothing compares to actually holding the thing, using it for a while, and seeing the benefits first-hand.

If you have an option to let your customers try your product, do it.

Have you ever been to an Apple store? They’re designed specifically to induce the endowment effect. Visitors are allowed to try their products and employees are instructed not to interrupt them. The newest iPhones and MacBooks are right there, ready to be used. You can play with them as long as you want. That’s called haptic imagery – the possibility of touching the product enhances the feeling of ownership. The longer you do so, the more intense the endowment effect becomes.

If you provide an online service, provide customers with free trials. All of the big players do – from Google, through Spotify, to Netflix. Netflix does it particularly well, not only providing a free trial but also removing friction and uncertainty from their registration process.

4. Money-back guarantee

Last but not least, to invoke the endowment effect, offer the customers a money-back guarantee. Yes, this logically means the customers need to buy the product first. The refund can not only eliminate possible uncertainties but also do one more thing.

The endowment effect says people value the products they own much more than the products they don’t. But the money-back offer means they will only get what they initially paid for it. And that suddenly won’t seem enough.

The endowment effect says people value the products they own much more than the products they don't. But the money-back offer means they will only get what they initially paid for it.

Summary

What is the endowment effect?

The endowment effect means we attribute greater value to things we own than to things we don’t. And we don’t need to actually own the thing – it just needs to feel like we do.

It stems from loss aversion – we hate experiencing losses about twice as much as we like gains. Because of that, we attribute more value to the things we own to compensate for their loss.

How to avoid the endowment effect?

Overall, ask yourself how much value the product provides to you. How often do you use it? You may find it’s not as useful as you thought.

If you’re a seller, do your market research and compare your price with the average market price. Ask yourself, how much money are you already losing by rejecting offers and whether you’d buy the product for that price if it wasn’t yours.

If you’re a buyer, watch out for free trials and try-ons. Also, businesses will use a clever persuasion tactic of describing the ideal future you can have with their products. Watch your imagination, it can run away with you quickly!

How to use the endowment effect in business?

There are 3 easy ways to leverage it right away:

- Let your customer imagine they already own the product.

- Make customers feel like a discount is already theirs.

- Let customers try the product.