Risk Aversion – Everything You Need To Know

Risk aversion might be the reason why you’re so hesitant to change something about your life and why your boss won’t approve that ambitious project of yours. Keep reading to learn how you can overcome it and use it to your advantage!

Article content:

Defining risk aversion

Risk aversion describes the preference people have when they choose an outcome that’s certain over one that’s uncertain. Most people dislike ambiguity, and when faced with a tough decision, they’ll generally go for the “safer,” risk-free option. This bias can manifest in various different ways.

Perhaps you’re hesitant to try that new breakfast cereal because you’re afraid you might hate it. I mean, you can’t go wrong with Cinnamon Toast Crunch! Or maybe you’re only willing to invest in low-risk investments with small returns because after all, it’s better than a regular savings account, right?

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Indeed, people hate risk so much that they’re even willing to “pay” for it!

And the “price tag” of risk aversion can be anything you’re willing to sacrifice in order to avoid uncertainty. It can be the boredom you feel when you’re munching away on Kellogg’s flakes because Cinnamon Toast Crunch was sold out and this was the only other “safe” option, or it could be that extra income you lose out on by sticking with a low-risk investment portfolio.

How does it work?

Risk is in every decision we face. In most cases, it’s not the same level of risk as jumping out of a three-story window into a six-foot swimming pool, but it’s omnipresent even in the smallest decisions we make.

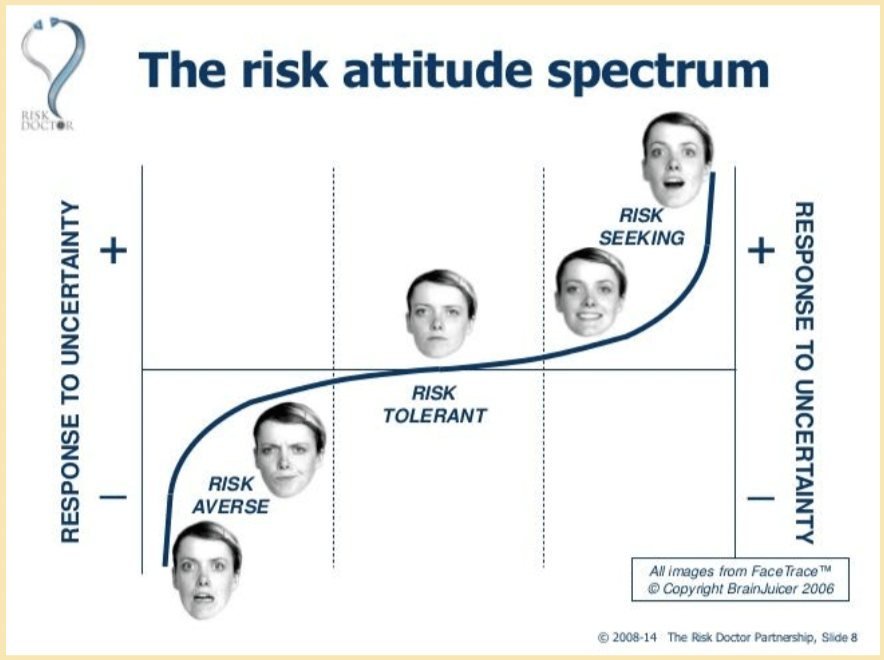

Humans, as distinct as we all are, have diverse levels of tolerance towards risk. This is why some of us can handle deep-sea diving, while others won’t dare go near a swimming pool without a lifeguard on duty. The ability to deal with risk is what determines our willingness to engage with it, and it varies from person to person.

The spectrum of possible risk attitudes is illustrated in this infographic:

Source: Seeking Alpha

Risk-averse people can’t handle risk, hence why they tend to avoid it. They seek absolute certainty in their decisions and are happiest when their level of risk is 0%. They’ll never go over the speed limit and would get a heart attack at the very thought of skydiving. Their investment portfolio will consist of bonds where the return on their money is low but certain.

Seems pretty straightforward, right?

Unfortunately, the reality gets a bit messier than that…

A person can drive very cautiously, adhere to every street sign, and drive a certain brand of car that’s known for its safety. But at the same time, they’ll smoke a pack of cigarettes a day and drink mega pints of red wine every night. As much as they value their personal safety on the roads, they really don’t seem to care about the dangers of drinking or smoking and are perfectly willing to take a gamble on whether they’ll get lung cancer or liver disease someday.

This behavior isn’t exactly ironic, as people’s risk preferences can vary from situation to situation. Just look at our smoking, alcoholic driver example: they’re extremely risk-averse when it comes to vehicle safety, but when it comes to putting chemicals in their body, it’s as if risk-aversion is thrown right out the window. They even exhibit these contrasting preferences simultaneously when they smoke and drive!

An individual’s desire to avoid risk can be gauged by what they’re willing to forego to avoid any risk whatsoever. The extent of their “sacrifice” is known as the risk premium. If the payoff of a decision equals or exceeds a person’s risk premium, the person will become indifferent to the risk and choose the uncertain option.

If the payoff of a decision equals or exceeds a person's risk premium, the person will become indifferent to the risk and choose the uncertain option.

This might happen if the risk-averse driver’s wife is having a baby. He might be fine with being 10 minutes late to work to avoid paying a speeding ticket, but he certainly won’t miss out on his child’s live birth!

Why does this happen?

Despite being fundamental to human behavior, studies on risk aversion’s origin and purpose are still in their infancy.

One theory applies evolutionary principles to risk aversion. It argues that risk preference is a consequence of our forebears living in hostile environments where being more risk-averse was key to their long-term survival.

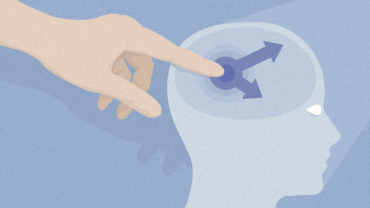

Risk-taking and risk-averse behavior correlate to a specific brain region, and changes there impact an individual's risk appetite.

The more widespread the risk encountered, the more irrational behavior is engrained. These biases were then passed down from generation to generation, influencing our risk preferences in today’s vastly different environments.

This is underpinned by studies that showed how there seems to be a neural basis for risk aversion. Neurologists discovered that risk-taking and risk-averse behavior correlate to a specific brain region, and changes there impact an individual’s risk appetite.

While no clear consensus currently exists, risk aversion is undeniably present in every living being (including animals!) and has a profound influence on our decisions.

While no clear consensus currently exists, risk aversion is undeniably present in every living being (including animals!) and has a profound influence on our decisions.

Is risk aversion a problem?

You might be wondering: if risk aversion developed for evolutionary safekeeping, isn’t it still important in protecting me?

On the one hand, risk-aversion can be useful. Risk-averse people are less likely to engage in unsafe health behaviors such as smoking. It’s also what keeps us from acting recklessly, like wagering our entire house in a bet or not looking both ways before crossing a busy intersection.

At the same time, risk aversion is associated with poorer decision-making when one is faced with complex and important decisions.

If you aren’t willing to risk taking a new job, you might miss out on important career advancements. Similarly, if you’re too afraid to invest in high-risk, highly rewarding mutual funds, you might end up with very little in your retirement fund!

A great example of how extreme risk aversion can impact someone’s life can be seen in the television show, A Series of Unfortunate Events. Click here to watch it!

Risk aversion can also impact our professional life. A 2021 study found that it leads to less effective and creative marketing campaigns for advertising agencies. Clients favored mundane solutions due to their familiarity while agencies, in fear of losing their clients, pandered and toned down their advertisement solutions.

Additionally, a lot of success in the business world comes from taking risks. Just think about all the start-ups, firms, and innovations that would have never existed without someone risking it all!

Risk aversion Experiments

The Allais Paradox:

One of behavioral economic’s most famous experiments is the Allais Paradox. It encompasses a choice set between two gambles and demonstrates human irrationality in the face of uncertainty.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty is a situation when your customer has incomplete or missing information. A situation when their questions, concerns, and fears aren’t answered.

Participants of the experiments were faced with the following two choices:

Option A:

- A 100% chance of winning $100 million

Option B:

- A 10% chance of winning $500 million

- An 89% chance of winning $100 million

- A 1% chance of not winning anything at all

Most participants preferred Option A over Option B.

Rationally, this doesn’t make any sense. From a financial perspective, the 99% chance of winning either $100 million or $500 million is well worth the 1% risk of going home empty-handed, and the expected value of Option B trumps Option A.

However, this is where risk aversion comes into play. Despite not being the best choice, the certainty of Option A is more attractive than the uncertainty of Option B. People are even willing to “pay” the extra $100 million as a risk premium to attain this certainty.

Insurance

Cicchetti and Dubin set out to explore risk aversion in an everyday situation, which we all face from time to time: phone insurance.

We all know the feeling. You buy yourself the newest, fanciest phone and when you go to pick it up, the salesperson asks you whether you want to add insurance onto it. It seems like a good deal; for just a couple dollars a month, your phone will get repaired if it breaks and you won’t have to pay the cost of repair. Just do it, right?

Well, people in 1994 thought the same thing. While no smartphones were available then, consumers could purchase protection from their local telephone company for their internal phone wiring. The deal was fairly similar to today:

Consumers had the choice of paying 45 cents a month for the telephone insurance or face the risk of paying the $55 total repair cost.

Still seems pretty great, no? Households in the research sample definitely thought so, as 57% of them purchased the wiring protection.

So where’s the catch, you might ask?

When broken down, the probability of having to pay the $55 repair cost was at 0.005 per month.

Hence, people were paying 45 cents a month to insure themselves against a “risk” that would average 28 cents per month, with a small risk of having to pay $55, and a minuscule risk of having to pay more.

People tend to vastly overestimate the small probabilities, thereby exaggerating their perception of risk in the given situation.

Again, from a financial perspective, it’s implausible to buy this insurance. The chances of actually having to pay any repair cost a month are below 1%, and even the total repair cost is a relatively small amount. Therefore, people should be indifferent to the risk of repair and just take home their phones without needing additional insurance.

However, cognitive biases don’t work like that. People tend to vastly overestimate the small probabilities, thereby exaggerating their perception of risk in the given situation. Through the purchase of insurance, they can eliminate this risk and alleviate the uncertainty of a what-if scenario.

A History

Prospect Theory

In the early 1970s, two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, advocated the idea of humans as irrational beings with limited mental capacities available. The idea was simple, yet groundbreaking, and created the field of behavioral economics.

Importantly, Kahneman and Tversky suggested that people’s choices were not based on dollar values, but on the psychological value of outcomes. This explains why people’s risk preferences vary!

For example, you and Jeff Bezos will probably value a $100 bill very differently. For you, it might mean a nice steak dinner at a fancy sit-down restaurant or relief from your worries of paying your bills after going on excessive online shopping sprees.

In contrast, Jeff Bezos will probably attach little value to a $100 bill, as it doesn’t make much difference in his billionaire-dollar lifestyle. He doesn’t have to worry about paying his bills and can even take a trip into space if he feels like it! Given this, your risk preferences for gambling $100 will vary, as your perceived value of it is significantly higher than Jeff’s.

Loss Aversion

A bit of a star in the circle of behavioral economics is loss aversion. As identified by Kahneman and Tversky, people value losses twice as much as they do gains.

To put it differently, the pain of losing something is approximately twice as psychologically powerful as the pleasure of gaining something. Hence why people will go to extreme (and irrational) lengths to avoid experiencing the pain of loss and engage in irrational behavior as a result. Great examples on how this affects us can be found here.

The pain of losing something is approximately twice as psychologically powerful as the pleasure of gaining something. Hence why people will go to extreme lengths to avoid experiencing the pain of loss and engage in irrational behavior as a result

You might be wondering, “Isn’t this similar to risk aversion?”

It is!!!

A useful way to look at these two biases is to imagine them as siblings. They share a certain set of traits and heavily influence each other. In fact, they even share the same last name!

However, there’s one important difference. While with loss aversion, your primary aim is to avoid losses, with risk aversion, losses take a secondary role. In risk aversion, it doesn’t matter how much you lose. Heck, people will even voluntarily accept those losses just to avoid taking risks. Experiments with CEOs showed that they’re willing to sacrifice future profit and revenue just to avoid projects with high levels of uncertainty.

The Certainty Effect

Another heuristic brainchild of Kahneman and Tversky is the Certainty Effect.

It occurs when individuals value certain outcomes over outcomes that are merely possible but uncertain. In layman’s terms, you’d rather take a guaranteed smaller win over the chance of winning more.

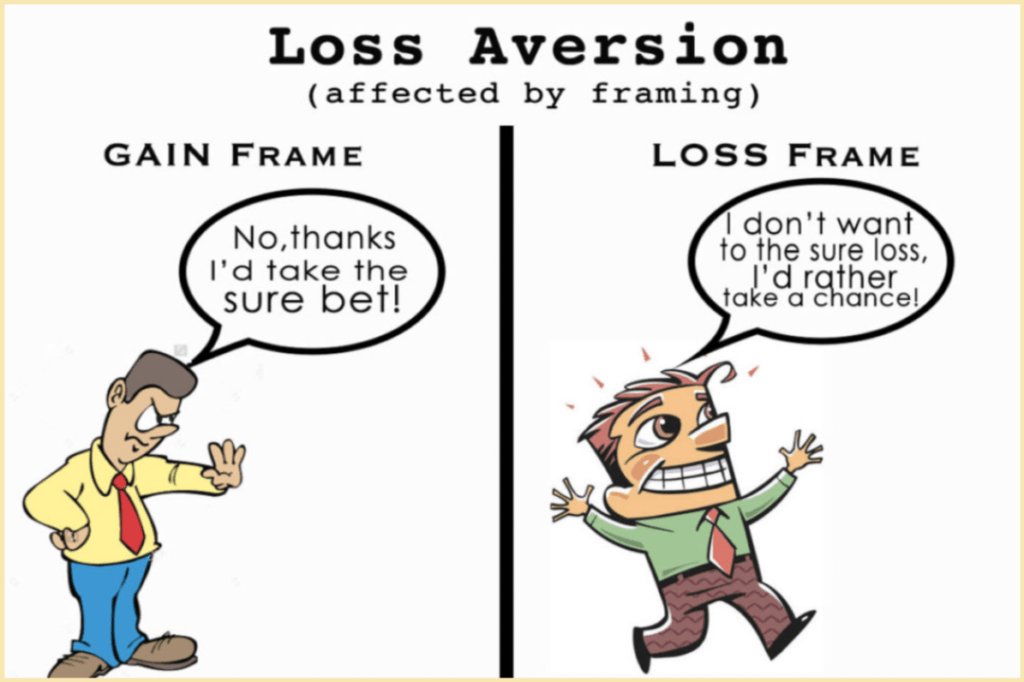

However, experiments have found that certainty is, in fact, not generally desired! Instead, people prefer certainty when presented with a potential gain, but will choose uncertainty when faced with a loss.

This influences risk aversion, as when aiming to avoid losses, we become more risk-seeking and are willing to gamble over a sure-fire loss in the hopes of losing nothing.

This logic is illustrated in the following comic strip:

Source: Linkedin

Overall, the Certainty Effect increases both our aversion to losses and our desirability of gains.

How to overcome it

Unfortunately, there’s no magic spell that can make irrational risk aversion suddenly disappear. Biases like these have often evolved over millions of years to protect us from danger, making our decision-making faster and easier.

But while this may have prevented our ancestors from suffering a horrific death, today its perseverance can mean that we’ll never be able to get completely rid of it. Luckily, we can learn to recognize the influence it has over us and use strategies to arrive at a rational decision instead. Keep reading to learn how!

Outsource the decision

Studies have shown that when making decisions for others, individuals become less risk-averse in the gain frame and less risk-seeking in the loss frame than when making decisions for themselves.

This indicates that decision-making for others heavily depends on the social value placed on risk. For example, you might be willing to risk your physical safety by taking diet pills, but would never put your friend in that same situation. In contrast, you might be too shy or afraid of rejection to introduce yourself to an attractive person you like at a party but would choose to risk it when making the same decision for your friend.

When making decisions for others, individuals become less risk-averse in the gain frame and less risk-seeking in the loss frame than when making decisions for themselves.

A theory why this happens is that when you’re making a decision for yourself, you tend to weigh gains and losses based on a fundamental reference point. However, when you’re making a decision for someone else, especially a total stranger, there’s no reference point, which means individuals might lean more towards risk neutrality.

In practice, this can imply that having an asset manager can actually lead to more rational investment decisions, as they tend to be more rational (i.e. risk-neutral) in making decisions for a third party rather than for themselves.

Similarly, physicians should avoid making medical decisions for themselves or for their friends and family, as these close relationships will hamper their professionalism. Instead, try asking a friend what they would do in your situation, or imagine giving advice to a friend in your situation.

Broaden the context

As we’ve already mentioned, people often act irrationally because they have a limited cognitive load. As a result, one bad habit they might fall into is focusing solely on the task at hand and the differences between the two options in an effort to simplify and focus on what differs.

However, most prospects can be decomposed into shared/distinctive traits in more than one way, and the actual outcomes are influenced by more than just the circumstances of a single decision.

Most prospects can be decomposed into shared/distinctive traits in more than one way, and the actual outcomes are influenced by more than just the circumstances of a single decision.

For example, when buying a new outfit, people often only consider the sticker price and how the clothes fit them. But, unfortunately, with this way of thinking you can end up with a whole closet full of the same old clothes, all because you failed to take into consideration other factors relating to your existing wardrobe or your overall financial situation.

The key here is to consider how you arrived at the options you’re faced with right now and reframe the decision in a broader context. For instance, you’re considering investing a percentage of your savings into an exciting new company, which you believe will be highly successful in the future. However, even just speculating with $100 seems petrifying to you, as you don’t have a crystal ball and can’t predict the outcome with certainty.

Here’s where reframing can give you comfort.

Look at those 100 dollars from the perspective of your overall bank balance. Does that $100 hold the same importance to you compared to the amount of money you have in the bank?

In most cases, losing a small amount of money won’t be a crushing loss and the shock will be absorbed by your additional income. So you can go ahead and gamble in confidence over a small amount. Who knows, maybe you’ll be investing in the next Microsoft or Apple!

Focus on the bottom line

Another classic mistake we make on a regular basis when trying to manage our risks is when we allow ourselves to be terrified of failure. In doing so, we work to manage and mitigate risks through extensive planning, thereby limiting our options.

The success of this mentality could be seen in the London Borough of Newham and its COVID-19 response. Rather than designing the ‘solution’ instantaneously, the focus lay on prototyping – starting multiple attempts that might have been imperfect but could quickly be adapted and improved.

By accepting and planning with uncertainty and possible imperfection, the risks were reduced. The worst outcomes didn’t seem to be as scary, and decisions could be made without the influence of fear. So, while other boroughs were still tittering with finding a solution, Newham had their COVID operation up and running.

Neat, right?

The good news is that this strategy can be effective on a personal level as well.

When faced with big life changes like looking for a new apartment, it’s easy to become overwhelmed by decision paralysis, or to seek comfort in what you know. So instead of spending hours on the internet researching the best neighborhoods to live in, simply schedule viewings of some apartments in various places. You can adjust your search radius as you go along, and maybe you’ll even stumble upon a hidden gem where you least expect it!

Develop a portfolio

You know how the old saying goes: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

The person who coined this was definitely onto something. If you go all in and bet on just one possibility, you’ll be worried the whole time about it failing. But if you hedge your bets and give yourself multiple chances to succeed, you can be more optimistic about at least one of them working out.

In this sense, decision-making is a numbers game. With enough attempts, some decisions will work out and even compensate for the flops.

Again, don’t forget to look at the bigger picture! When viewed in a vacuum, every decision can seem too risky, but when imagined over your entire lifespan, they’ll end up seeming rather minuscule.

Just like with our last example, give some thought to your possibilities and make decisions that will balance each other out. Thus, even if you’re uncertain about the outcome of a decision, you can rest assured that your strategy will work out and that you’ll have a safety net to fall back on.

Give some thought to your possibilities and make decisions that will balance each other out. Thus, even if you’re uncertain about the outcome of a decision, you can rest assured that your strategy will work out and that you’ll have a safety net to fall back on.

Depersonalize risk

Depersonalizing risk can be just as important and successful! Recall how Kahneman and Tversky determined that losses loom two times larger than gains, so the thought of past failures can sting for a long time and even deter you from taking risks ever again.

To steer clear of this guilty conscience, aim to separate the success of a project from yourself. Try to evaluate yourself based on your overall activities instead of punishing yourself for taking risks.

The same applies to companies. Traditionally, larger organizations reward success and punish failures, thereby creating managers who are risk-averse. I mean, why wouldn’t they be, right?

Risk aversion might be bad for the company, but usually good for a manager’s career. They’re evaluated based on every decision they make instead of their long-term performance, with incentives and control processes encouraging this behavior.

To overcome this wherever possible, managers should be evaluated based on a portfolio of outcomes and not the success or failure of a single project. By taking a more understanding stance in dealing with failure you can depersonalize it. This breeds managers who are more comfortable with handling risk without fearing the detrimental consequences to their career.

One environment where these practices have already been implemented is in oil and gas exploration. Here, executive rewards are not distributed based on individual performance, but rather on the combined achievement of up to 20 people! Through the pooling of risk, decisions made in this environment were actually found to be more risk-neutral. So, don’t hesitate, go change your corporate reward structure right now!

Examples and case studies

Let’s look at some examples of how businesses have successfully addressed risk aversion.

Online shopping

Let’s start with a situation we’ve all faced: to buy or not to buy.

Many risk-averse customers tend to abandon their online shopping carts in favor of finding something more certain in real life, leading to millions in lost revenue.

Especially in an online context, this decision is riddled with uncertainty. Not only have we not seen or touched a garment being sold online, we also don’t have any information on the most crucial part of all: will it fit us?

This question alone can feel risky enough, but customers usually have to repeat it with every single new item, amplifying the uncertainty every time. In light of this, many risk-averse customers tend to abandon their online shopping carts in favor of finding something more certain in real life, leading to millions in lost revenue.

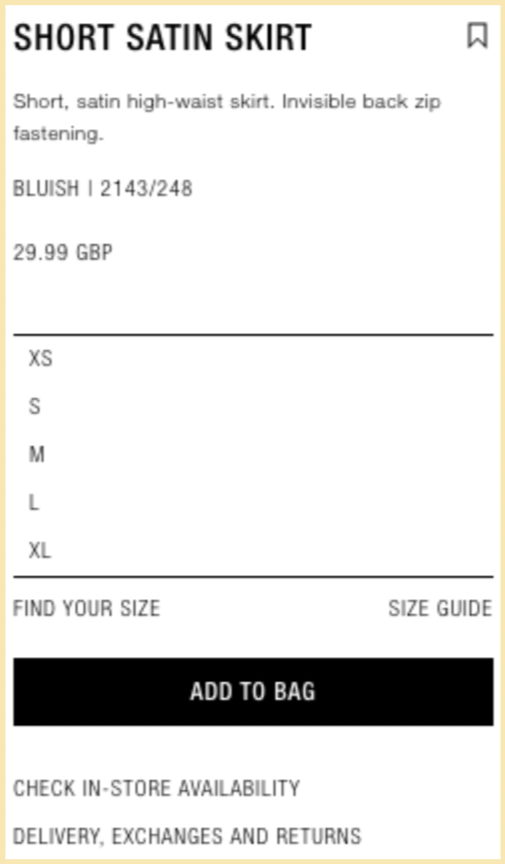

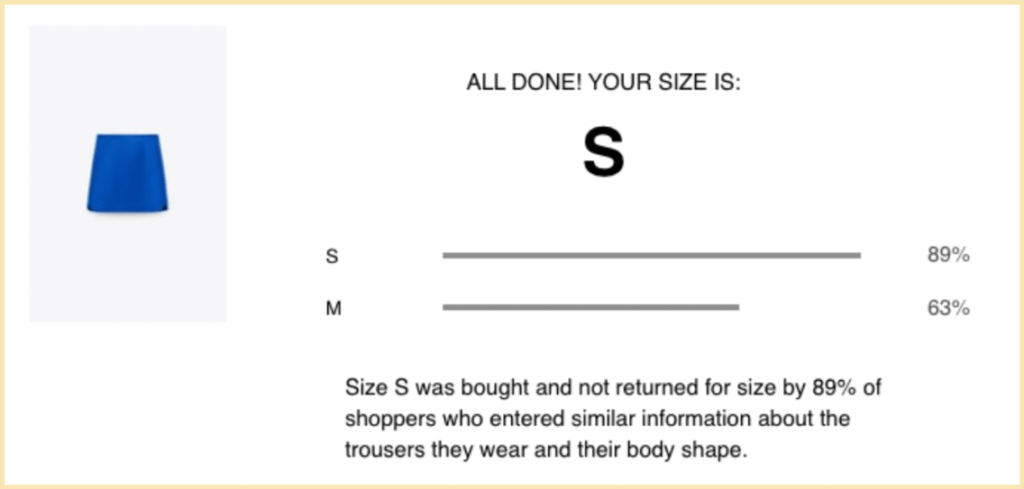

Spanish fashion retailer Zara recognized this dilemma in its customer journey and found a great way to give their customers certainty in their purchase.

When adding an item to your cart and choosing your size, the Zara website will meet you with a little prompt to “Find your size.”

Source: Zara

After clicking on it, the website takes your measurements, fit preferences, body shape, and age into account in order to provide you with a personalized estimation of your clothing size.

By simply completing these steps with the customer, Zara makes the option of buying feel “safer.” You can be certain that the dress will fit your body, and the perceived risk of ordering will diminish.

Quite a neat way to ease risk aversion, right?

To learn more about how Zara uses consumer psychology in their online sales funnel, be sure to check out our case study!

Auction design

Risk aversion is not always a disadvantage for businesses. Let’s take a look at how risk aversion can actually get people to spend more money.

Kong (2020) compared sealed-bid auctions (auctions where bidders submit their bids simultaneously and anonymously) to English-style auctions in New Mexico (auctions where the price of an item is increased through continuous bidding among bidders).

Surprisingly, he found that sealed-bid auctions generate about 30% higher revenue than English auctions! Why is that?

Well, the answer is…… drumroll……. risk aversion!

Bidders in sealed-bid auctions face a lot more uncertainty in terms of the circumstances of their bidding and the possible outcome of their actions. They’re unaware of how many other bidders there are and how much others have bidded, so they’re motivated to reduce this uncertainty by offering a higher initial bid amount.

In their logic, more money = a higher level of certainty in winning the auction, so bidders who are otherwise risk-averse will end up bidding several times the publicly announced price, even when they’re the only ones bidding. This is the risk premium risk-averse bidders are willing to pay in order to obtain the item with a greater level of certainty.

By using the sealed-bidding format, the New Mexico State Land Office could observe a significantly higher average revenue per item than similar English-format auctions, with an estimated difference of $26,974 per item!

How to use it in business?

Guarantees

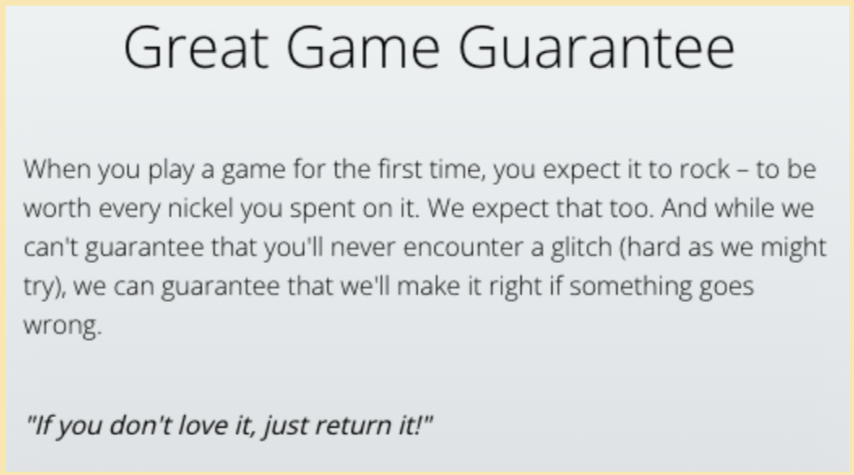

One of the most simple and reliable ways to build customer confidence in your product is by offering guarantees.

Remember, even if you have the best product on the market, if the customer has any doubts about its value, they won’t buy it. Period!

A good guarantee will nudge people in two ways. With a guarantee, customers can:

- feel confident that they won’t be stuck with a purchase they don’t like (it relieves uncertainty around the product and prevents buyer’s remorse).

- get the illusion of control by potentially returning it at anytime (a loss of control is the biggest reason why customers freeze up and abandon the buying process).

Additionally, the very act of offering a strong guarantee gives buyers the impression of your belief in the product’s high value.

A great example of this can be seen with EA Games:

Source: EA

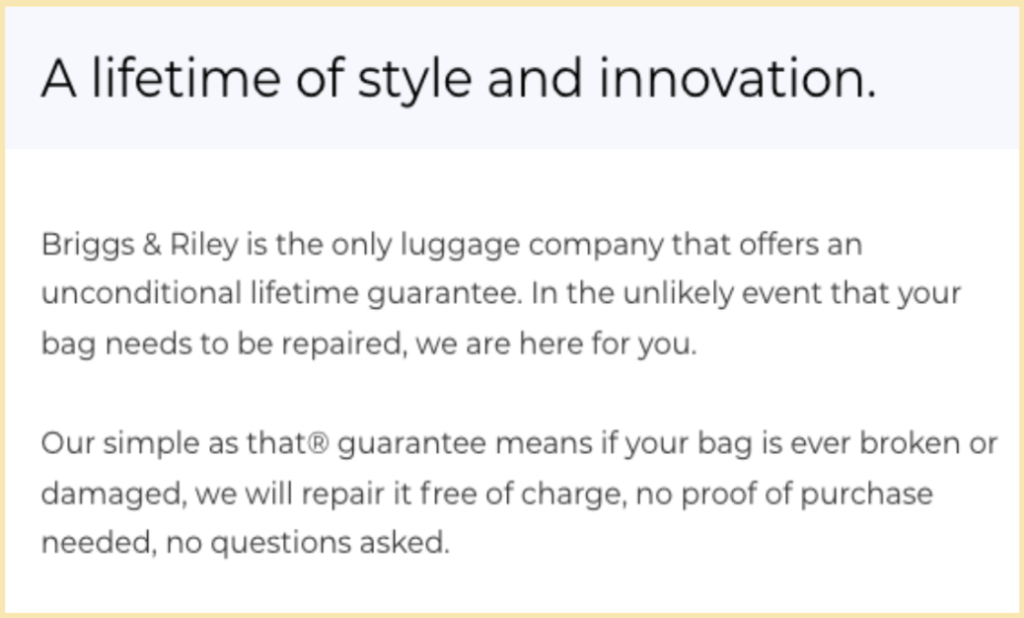

This halo effect of value is also created by travelware manufacturer Briggs and Riley:

Source: Briggs and Riley

It works well because it’s clear, concise, and generous in its time frame, conditions, and commitments. Additionally, it’s friendly! No intimidating asterisk, legal text, or fine print, just a simple and clear explanation. If you keep your guarantee, short and sweet people will love it and buy your product because it feels safe.

Testimonials

A second common but effective sales method is providing testimonials. By having people vouch for your product, others will buy it too.

This effect, known as social proof, is baffling in its simplicity and effectiveness. In cases of uncertainty, people will turn to contextual cues and heuristic indicators to make a decision, in which case social proof works best.

I mean, if 30 other people liked it, why wouldn’t you?

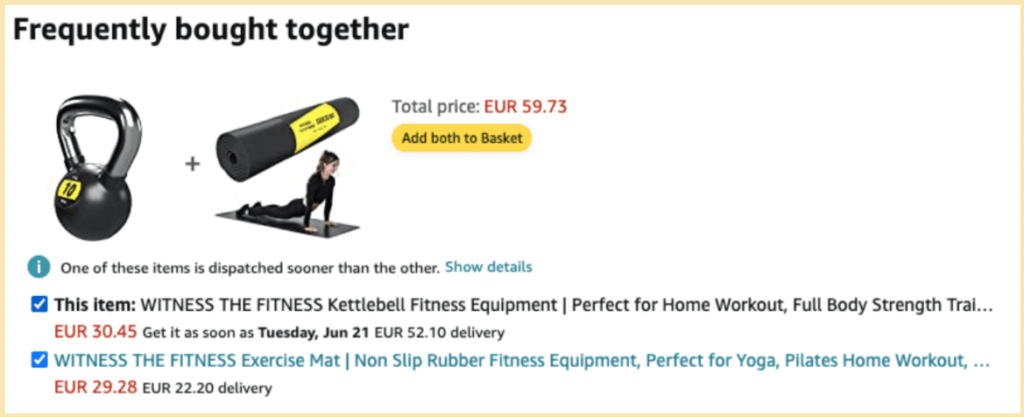

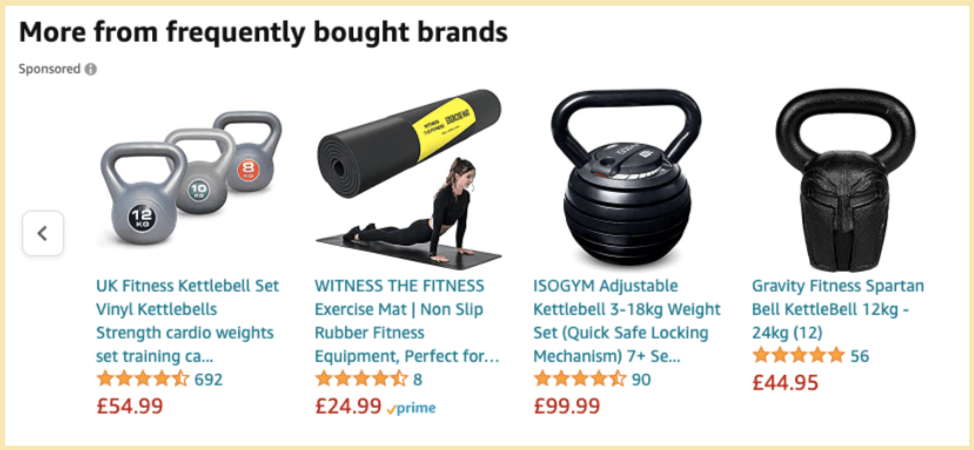

This logic often influences us without us ever noticing it. Amazon reduces consumer choice overload by showcasing examples of other customers who made similar purchases.

Surely you’ve seen the “Frequently bought together…” bracket when shopping on Amazon? This feature provides the shopper with social proof of others buying the same item and reinforces the idea of the item being the right purchase to make.

Source: Amazon

What’s more, that social proof can be expanded upon by suggesting additional items!

Source: Amazon

Similarly, do you remember the example of Zara in the case studies section?

Well, the size measurement system utilizes social proof brilliantly.

Just take a look:

Source: Zara

Do you see how social proof persuades you on what size to pick?

By simply showing a statistic of the percentage of people satisfied, you feel more confident in buying the item for yourself.

Keep the consumer buying process simple

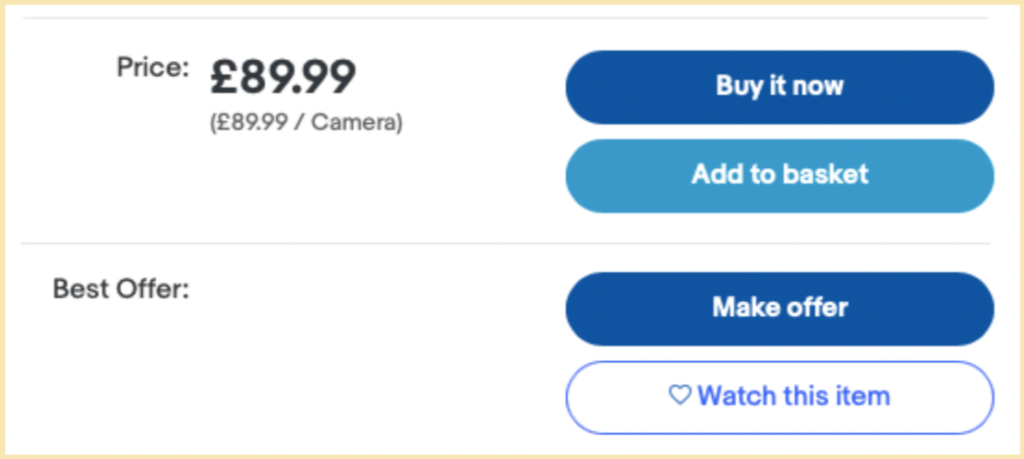

eBay built their website with a smart trick to awaken consumer risk aversion. In addition to their classical auction-style buying process, the second-hand retailer also included a very important option on their website: the buy-it-now button.

Source: eBay

The buy-it-now option increases revenue by creating a choice architecture that nudges agents to become more risk-averse. The contrast between the “buy it now” and “make an offer” options highlights the uncertainty of the bidding option and drives customers to pay a higher price in exchange for obtaining the item with certainty.

Would you have spotted this on your own?

Make it flexible

Consumers often end up “freezing” the buying process due to feeling mentally overwhelmed with their decision-making and associating change with a loss of control.

The same principle applies multifold to risk-averse buyers who will jump ship at even the slightest sign of risk. So what can be done to recruit such hesitant buyers?

Offer flexibility!

The Amazon Web Service (AWS) recognized that for many business clients, it’s impossible to predict the quantity of computing power required in the coming period and would therefore refrain from making a purchase decision. This was especially typical for risk-averse clients trying to avoid overspending on an uncertain subscription service.

So, AWS revamped their services to create an offering specifically targeting this buyer group: pay-as-you-go pricing.

See an example of their introduction here:

Source: AWS

Why does it work?

AWS responds to perceived uncertainty by eliminating it. Gone are people’s concerns on required service quantity or time commitments for an on-demand service. You pay exactly what you consume!

You might be wondering, “How is this worth it for Amazon?”

Well, the on-demand cloud service described here has higher pricing than a standard period subscription. However, since the target demographic are risk-averse buyers, the promise of certainty trumps relative price concerns. A useful trick to remember!

Unfortunately, this article ends here, but if you’re keen on learning more about uncertainty, click here.

Summary

What is risk aversion?

Risk aversion is our preference to prioritize certainty over uncertainty.

How/why does it work?

It works because people make decisions under uncertainty, based on their given risk appetite. If influenced by risk aversion, this bias will drive people to choose the sure-fire option, even when they have more to gain from the riskier option.

How can we avoid risk aversion ourselves?

While it’s not always easy to stop and think about what the rational decision might be, it can be helpful to examine your decision-making process and determine how much your choice of action is influenced by fear or uncertainty. Test yourself on how much the allure of certainty is influencing your decisions, and whether it’s really as important to you as you perceive it emotionally.

As the uncertainty of a decision is what drives risk aversion, by decreasing ambiguity, you can actually ease its influence. If you’re willing to think about risk, you can shield yourself against it and see that even the worst-case scenario is not the end of the world.

How can you use risk aversion in business?

If you want to take advantage of risk aversion, there are two overall important things to keep in mind:

- It’s your responsibility to know your customer’s risk preferences.

- Your risk-averse customers will respond negatively to any risk factors in your buying process.

So, you have to look at your business from your customers’ perspective, understand their risk appetite, what kind of risk they embrace or reject, and how that affects their willingness to convert.

As long as you have a good understanding of that, then you’re well on your way to designing interventions that encourage your customers to change their behavior. Examples of this can include offering guarantees, showcasing testimonials, emphasizing the certainty of a particular choice on your website, and providing on-demand services.

Just remember to be moral about your interventions. If your customer has a bad experience with you, it’s possible they’ll never come back. Especially if they’re risk-averse!