Hyperbolic Discounting – Everything You Need to Know

Article content:

Definition of hyperbolic discounting

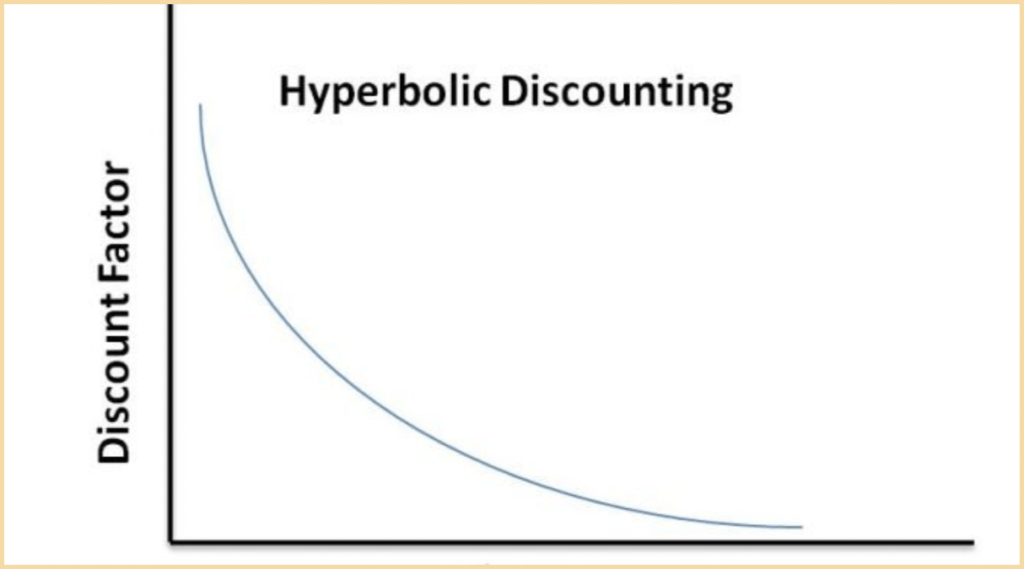

Hyperbolic discounting is our tendency to prioritize immediate rewards over long-term benefits, even if the immediate reward is objectively less valuable. It’s a type of cognitive shortcut, a so-called heuristic, that evolved through time and was supposed to simplify our decision-making.

Source: Conversion Uplift

How does hyperbolic discounting work?

You’ve actually encountered this bias way more often than you think. It happens every spring when you dream of your summer beach body. You decide to cook your own meals and eat healthy from now on.

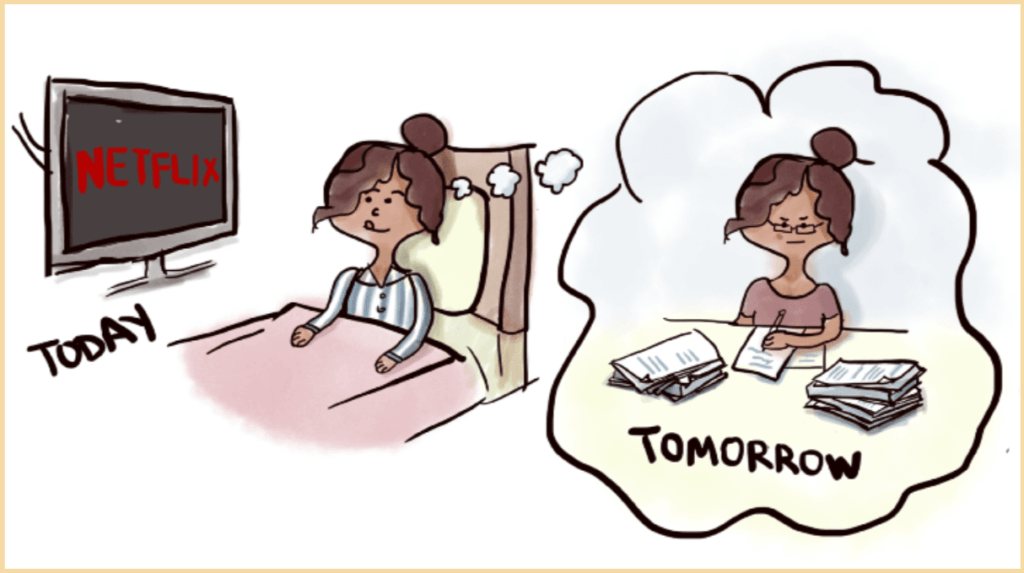

But what happens a couple of days down the road when you arrive home from work exhausted, itching to watch Netflix and just chill for a while? Pizza it is!

It happens every time you procrastinate. One more task to finish today so you can breathe easier tomorrow? Nah, that’s a future you problem now.

Source: Medium

In both of these cases, you just chose immediate gratification, even when delaying it would have been better for you.

Interestingly, studies show that the situation changes if we don’t talk about immediate reward, but a reward in the distant future. For example, if you were told today that you’ll be overwhelmed with work a year from now if you procrastinate for a whole week beforehand, you’d probably make a rational choice today to solve some tasks the week before.

Productivity Guy explains hyperbolic discounting nicely in about 2 minutes here:

Source: YouTube

Why does it work?

We are hard-wired to opt for immediate gains

There are multiple reasons why this happens. The first, as usual, is evolution. Our brains were never wired to make rational choices. No, they evolved to survive. And that, for the longest time, meant making quick decisions.

Unfortunately for today’s us, our cavemen ancestors never had to choose between eating a whole antelope at once versus investing in retirement funds. The best decision they could make was to eat the whole thing, as there was no certainty another meal was coming for a while. Immediate sure things = survival.

That has influenced the evolution of our nervous system. The reward causes a quick rush of the feel-good neurotransmitter, dopamine. The feeling of satisfaction we get after this reward ensures we will opt for the same choice again next time.

The feeling of satisfaction we get after this reward ensures we will opt for the same choice again next time.

Delaying gratification means opting for an uncertain outcome

The future is distant. Who knows what it holds? If we chose $120 a week from now instead

of $100 today, something might happen before then. There’s a big chunk of uncertainty and boy, do we hate uncertainty!

It makes us feel like we’re not in control, which again, represents a potential danger from an evolutionary perspective. That’s why we tend to avoid such situations. In fact, it’s a top sales killer precisely because the slightest uncertainty can stop customers from purchasing.

It also makes us go for certain outcomes – that is, things we can get right now. Not tomorrow, not next year – NOW.

Hyperbolic discounting experiments

The Stanford marshmallow experiment

The Stanford marshmallow experiment is a famous study by Walter Mischel that took place in 1970. In this study, a researcher offered a child one candy now or two candies in 15 minutes (we strongly suggest trying this with your own children).

There were a total of four conditions. :

- The child was left in the room with only the immediate reward (the tempting candy)

- The child was left in the room with both the immediate reward and also the delayed reward – the second candy

- The child was left in the room with only the second candy – the delayed reward

- The child was left in the room alone, with no reward they could physically see.

Then, the researcher left the child alone in the room with the one candy. If the child could stand the whole 15 minutes without the immediate reward, they were given both the immediate and the delayed reward – that is both sweets.

The results showed that in the second condition (with both rewards in the room), none of the 8 children made it through 15 minutes. But 6 out of 8 did make it when they couldn’t see either of the sweets.

Interestingly, follow-up studies found that children who were able to wait longer for the two candies were more successful in multiple areas later in life, such as SAT scores or body mass index. Remember that the next time you’re about to procrastinate!

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Get your money now, or in a week

Another classic experiment is one by Leonard Green, Astrid F. Fry, and Joel Myerson. The researchers gave people a simple choice.

They could either pick a fixed-amount reward (e.g., $1,000) that they could get after a week, a month, 6 months, 1 year, 3 years, 5 years, 10 years, or 25 years. Or, they could pick an immediate reward that varied in amount (e.g., from $1 to $1,000).

The longer the delay, the greater the probability that the participant would opt for the immediate reward.

In the end, participants had to make a choice – for example, either pick $1,000 in 10 years or $650 now.

Can you guess the result? Yes, in general – the longer the delay, the greater the probability that the participant would opt for the immediate reward. With slight differences, this trend was observed in children, young adults, and older adults.

History of hyperbolic discounting

Hyperbolic discounting was first teased in Richard Herrnstein’s “matching law”. He noticed that people do things in proportion to the amount of reinforcement that they receive for those behaviors.

In other words, if you were to choose between either scrolling through TikTok for 10 minutes, or watching your favorite sports team for 5 minutes, you would choose the option that brings more enjoyment. In this case, TikTok. More joy = a better option.

Moreover, he noticed that people didn’t choose purely based on how big the reward was, but also on how immediate it was.

Following Herrnstein’s research, George Ainslie pointed out that when the smaller, earlier reward is preferred, it can be overridden by increasing the delay for both rewards by the same amount. This meant that the choices were not consistent in time, but rather followed a hyperbolic curve.

When the smaller, earlier reward is preferred, it can be overridden by increasing the delay for both rewards by the same amount.

Since then, many studies have shown that this phenomenon not only affects our daily choices and whether we tend to procrastinate, but is also present in drug abuse, gambling dependence, or alcoholism.

How to avoid it

As with any other hard-wired bias, hyperbolic discounting is not easy to avoid. It can be done, but how may depend on the specific situation. Let’s go through some techniques that can help you fight it.

Chunk big goals into smaller, more digestible ones

This may be the biggest reason we avoid our responsibilities. Goals seem like they will take us a lot of time and be a total pain.

What helps? Try to break them down into more specific steps. For example, if you are studying for a final exam, learning the whole book seems terrifying. But how about 5, maybe 10 pages a day? That seems much more doable, doesn’t it?

The same principle applies in your work, when you’re training for a marathon or when you’re learning a new language.

Commit to your tasks

Chunking big goals down is a great start. But how can you make sure you won’t avoid even these smaller goals? Commit to them.

In other words, simply plan when exactly you will do them. Create a blocker at a specific time in your calendar.

There is plenty of research that says that once we commit to doing something, we are much more likely to actually do it. For example, people who commit to sending a portion of their future paychecks to their retirement funds end up saving much more than those who do not commit.

Once we commit to doing something, we are much more likely to actually do it.

Reward yourself

You broke big tasks down, planned them in your calendar, and actually finished them? Great! It’s time for a reward!

Let’s say your goal is to run a marathon. Did you manage to run 10 miles today? Reward yourself with your favorite Netflix show. The next time a small task is planned in your calendar, that kind of reward can be a great motivator.

As a bonus, a short-term reward system like this will eventually lead to creating a new habit. Next stop, an ultramarathon!

Be explicit about what you can lose

Did you ever hear about loss aversion? Yes, people hate losing so much that it’s actually got its own term. To sum it up, we hate experiencing losses about twice as much as we like experiencing gains.

When you’re itching to opt for an immediate reward, just imagine what it will actually cost you. Let’s say your goal is to lose weight. If you don’t go for a run today and treat yourself to some pasta instead, what can this lead to? The pounds will keep piling on and you can say goodbye to your summer beach body.

Examples and case studies

Political populism

This example may be more or less visible depending on where you live, but you are surely familiar with it.

When a government is elected for 4 years, it might be very tempting to prioritize political gains instead of the public good. Something that looks sweet and leads to short-term gains for certain people, for example, a one-time contribution to traditional families, can increase the administration’s popularity.

And the long-term consequences? That’s for another time. Literally.

Short-term thinking causes climate change

This is perhaps the best example of short-term thinking. Even when an overwhelming majority of scientists are warning very loudly that it may already be too late to reverse climate change, some people still opt to max out their ACs on hot days or to throw all their garbage in a single bin.

Turning the AC down a few degrees or separating waste is not that hard, but people underestimate the long-term effects, as they think these are very distant. Instead, they opt for immediate comfort.

Loss aversion decreased high school dropout rates by a third

The local government decided to change the law so that under-aged students who chose to quit school early also lost their driving licenses.

In Loewenstein and Thaler’s 1989 paper, researchers discussed the hyperbolic discounting effect in high school students. In West Virginia, it was causing students to underestimate the long-term consequences of dropping out of school.

The local government decided to change the law so that under-aged students who chose to quit school early also lost their driving licenses.

This implementation of loss aversion had a significant effect. After the law was implemented, high school dropout rates fell by a third.

Fighting hyperbolic discounting to save more

Saving is not the easiest or the most pleasant thing to do. You literally need to regularly deny yourself money that you have earned from your hard work, just so you can have more later on. That’s exactly the kind of condition where hyperbolic discounting thrives. So, what can you do about it?

A retirement program called Save More Tomorrow fights it effectively. If employees decide to join the program, they agree that after every paycheck, a certain amount of money will automatically be sent to their retirement fund. What is more, they also agree that the amount will increase along with any pay increase.

Save More Tomorrow uses the above-mentioned commitment to fight the bias. The employees make just one decision that influences their savings for years to come.

How to use hyperbolic discounting in business

Create immediate benefit for your customers

If you give something to your customers right away, it will be more effective than discounts at later stages.

If you give something to your customers right away, it will be more effective than discounts at later stages.

Think about how you can create this kind of reward. Are you offering people a financial service? Consider giving them a credit card for free. Are you a telco operator? Reward new customers with free calls or data.

This can serve as a great motivator to gain new customers and can also improve your CX right from the beginning.

Allow your customers to pay later

As customers underestimate costs at later stages, they have a smaller impact on their purchase decision. Simply put – buy now, pay later.

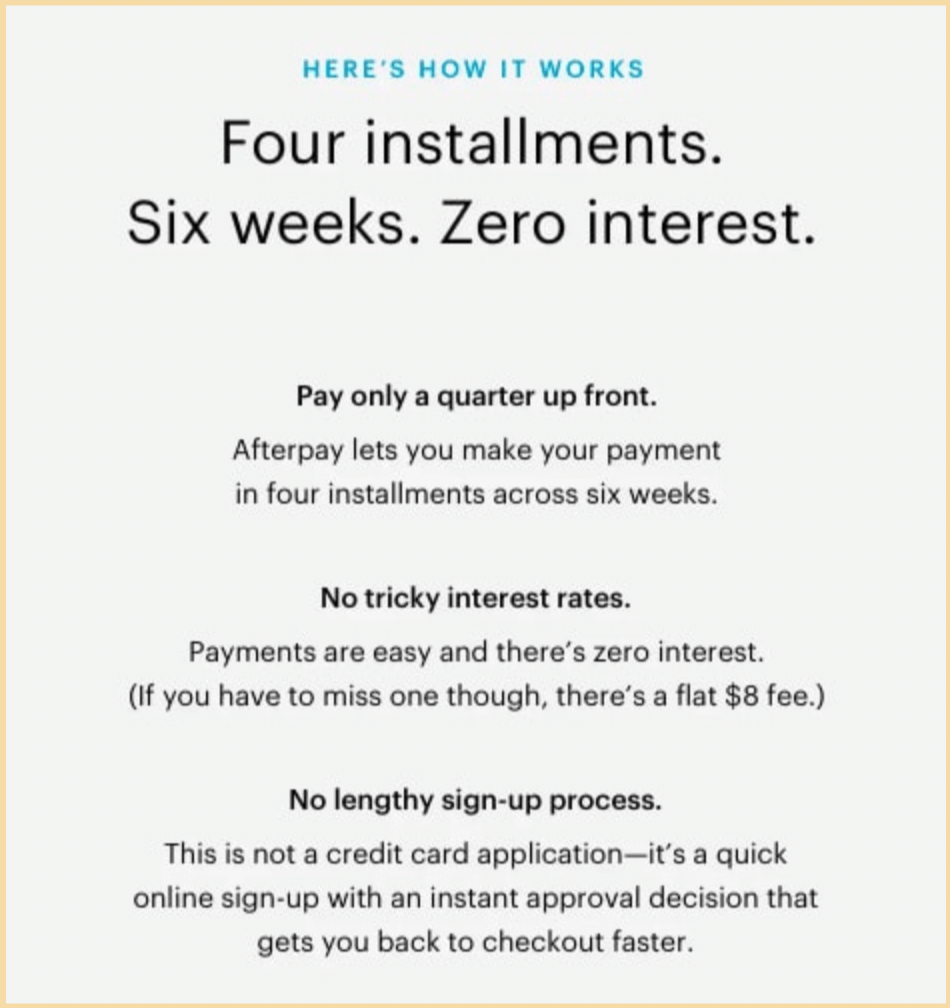

Everlane is a great example of this. It’s a clothing store that uses a method called Afterpay. Customers can simply buy their clothes now, pay a portion of the price upfront, and the rest in four installments.

Source: Milled

As every purchase usually comes with the pain of paying, you postpone this pain to later but allow your customer to enjoy the product immediately.

Reward your customers regularly through loyalty programs

As the basic principle of hyperbolic discounting is that people love immediate rewards even if they are not that big, this can easily be used in loyalty programs.

This leads to more frequent rewards, which consequently will make your customer buy more often, as they will anticipate their reward.

If your customers collect points for every purchase, make sure it doesn’t take them forever to collect enough points to get their reward. Instead, you can make the prizes smaller, but reward them more often.

This leads to more frequent rewards, which consequently will make your customer buy more often, as they will anticipate their reward.

Offer free shipping for orders over a certain price

Everyone has been there. You’re about to pay for your online order, but the shipping costs seem a bit too high. But hey! You can purchase one more thing and the shipping costs disappear! Suddenly, you were never more certain that you could use a new coffee grinder.

Rational? No. You’ll end up paying more than with the shipping cost. That’s because you prefer the immediate satisfaction of not paying for shipping today (and also getting a new coffee grinder) over future savings.

When you set a total price below which your customers no longer have to pay for shipping, it’s a gift you offer them immediately.

Summary

What is hyperbolic discounting?

Hyperbolic discounting is a cognitive bias that causes us to prefer immediate rewards over long-term benefits, even if the immediate reward is objectively less valuable.

From an evolutionary perspective, immediate reward meant a higher chance of survival. That’s why hyperbolic discounting is hard-wired and very hard to get rid of.

Opting for a more valuable reward in the distant future also means opting for an uncertain outcome. As we are naturally ambiguity-averse, we prefer a certain outcome in the form of an immediate reward.

How can we avoid it?

Are you facing a task that looks like too much of a pain? That’s usually why people procrastinate. Break it down into smaller tasks and plan when exactly you will work on it. After each smaller task is done, reward yourself.

Loss aversion can be effective as well. Simply, be very explicit about what opting for an immediate reward can cost you in the long term.

How can you use it in business?

Customers want something now, not in the future. Treat new customers with a gift right away and provide them with frequent rewards along the way.

Loyalty points can be a useful tool here – simply give your customers smaller gifts more often. This will also make your customers buy more often, as they will expect their reward.

An effective way of using hyperbolic discounting is to allow your customers to pay later. The reason we don’t buy everything we want all the time is the price and the pain of paying. Once you delay that payment to the distant future, it’s suddenly not that painful.