Cognitive Bias – Everything You Need to Know

Article content:

Definition of a cognitive bias

A cognitive bias is a recurring error in thinking that’s been observed in many people across different situations.

Cognitive biases influence the way we perceive and interpret information. They can cause us to make decisions that aren’t based on facts and behave in ways that don’t follow logic.

Cognitive biases are a fundamental concept in behavioral economics. Biases affect us all, regardless of intelligence, expertise, political preference, age, or gender.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

What’s the difference between a heuristic and a bias?

Cognitive biases and heuristics are two closely related concepts – but they are not the same thing.

A heuristic is a simple rule that lets us make decisions quickly with minimal mental effort. In other words, a heuristic is a mental shortcut.

Whilst similar, cognitive biases describe systematic mistakes in thinking. Many cognitive biases are produced by the misapplication of heuristics when the brain attempts to simplify complex information but draws the wrong conclusions.

How do biases work?

Behavioral scientists have observed and demonstrated many different types of cognitive biases in everyday behavior.

There are currently at least 150 documented cognitive biases. Different biases impact our judgments and beliefs in various ways. A few common ones include:

Anchoring bias

Anchoring bias is the tendency to place an irrational emphasis on the first piece of information we encounter.

Let’s say you’re trying to estimate the height of a building. While you’re thinking, a friend throws out a random guess. Even if you don’t think their answer is accurate, evidence suggests that your response is likely to be affected by theirs.

Status quo bias

Status quo bias causes us to favor keeping things in their current state, even if avoiding change means missing out on potential benefits.

Imagine you have an old mobile phone and are sent a promotion from a rival provider offering an easy transfer to a newer device for less money. Months later, however, you still haven’t taken them up on the deal – that’s status quo bias.

Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the well-known tendency to pay greater attention to information that confirms your pre-existing beliefs.

For example, employees in an end-of-project review might focus on data that presents their work as a success or as a failure, depending upon their preconceived opinions about how things went.

Present bias

Present bias is the inclination to make decisions based on present circumstances and to irrationally prioritize nearer rewards.

Everybody knows that preparing a healthy meal and going to the gym is an evening well spent, but present bias can make staying on the couch and ordering takeout more appealing.

Why do cognitive biases exist?

The systematic thinking errors we call cognitive biases exist thanks to our brains’ love of efficiency.

All of our actions are constrained by time and energy, which means our brains have evolved to run on limited bandwidth. As a result, we’re not perfectly rational beings and tend to prioritize faster, actionable answers over slower, more accurate thinking.

But because heuristics are speed-oriented over truth-oriented, they don’t always track with logic. It’s this discrepancy that causes biases in our memory, attention, and beliefs.

Heuristics, these strategies for efficient decision-making, are important evolutionary adaptations. They work well enough of the time to be advantageous for our survival.

As psychologist Hal Arkes explains, “the extra effort required to use a more sophisticated strategy is a cost that often outweighs the potential benefit of enhanced accuracy.”

But because heuristics are speed-oriented over truth-oriented, they don’t always track with logic. It’s this discrepancy that causes biases in our memory, attention, and beliefs.

What impact do biases have?

In daily life

While we can become better at noticing our cognitive biases, and thereby reduce their impact, it’s almost impossible to remain bias-free. As a result, we spend our days continually walking around under the influence of multiple biases.

Over the course of a single day, present bias might cause you to spend that spare $200 on another pair of sneakers instead of investing it in your 401K.

The actor-observer bias might convince you that, while you were forced to throw your trash on the ground because the city doesn’t provide enough waste bins, other people litter because they just don’t care as much as you.

And availability bias might make you decide it’s faster to drive to work instead of catching the bus because you watched a news segment on how public transport is slower for some people in a different town.

In business

Cognitive biases affect businesses and their customers alike. Inside companies, HR teams try to reduce the effects of bias during interviews by following objective frameworks. Product designers use focus testing groups to see beyond their own perspectives, and marketers create content that deliberately appeals to common customer biases.

Biases often make customers more susceptible to marketing – and more or less loyal to brands and products.

For example, a product tag might use anchoring bias to make a price seem more attractive, by placing a higher “original price” next to a lower “sale price.”

Or, a “you still have items in your cart” email might trigger the Zeigarnik Effect, which describes how our attention is biased towards unfinished tasks.

Source: doist

The most famous cognitive bias experiments

Cognitive biases are a fundamental area of study in behavioral economics – and no behavioral scientists are more connected with the subject of cognitive biases than Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

Here are three of Kahneman and Tversky’s most famous demonstrations of cognitive bias:

The law of small numbers

The first study in the current program of cognitive bias research was performed by Tversky & Kahneman in 1969 and published in a 1971 paper.

In the study, the pair asked 84 psychologists to analyze the accuracy of a piece of statistical psychology research during a meeting of the American Psychological Association.

Even experts display biases when producing answers based on intuition, suggesting that our intuitions often derive from non-rational decision-making processes.

When they collected the responses, Tversky & Kahneman found that a majority of participants displayed an “erroneous intuition about the laws of chance,” despite their expertise – and the fact that they would have been capable of correcting their error given enough time.

Tversky & Kahneman concluded that even experts display biases when producing answers based on intuition, suggesting that our intuitions often derive from non-rational decision-making processes (heuristics).

Judgment under uncertainty

Kahneman and Tversky’s influential 1974 paper, Judgement under Uncertainty officially introduced the concept of heuristics and demonstrated two common biases that can arise as a result of using them: availability bias and anchoring bias.

To demonstrate anchoring bias, Kahneman and Tversky asked two groups of participants to estimate the percentage of African countries that are members of the United Nations. Before each group submitted their answers, a researcher spun a roulette wheel to produce a random number.

The group who were shown the random roulette number of 10 guessed that 25 African nations were part of the UN, while the group who were shown the number 65 guessed there were 45 nations. Despite being random, the roulette numbers became anchors.

To demonstrate availability bias, one of the experiments Kahneman and Tversky conducted involved showing groups of participants lists containing an equal number of men and women and asking participants to judge the ratio of genders.

When the lists contained the names of famous men and women (which are memorable and more mentally available) participants “erroneously judged the classes consisting of the more famous personalities to be the more numerous,” every time.

Framing effects

Another famous example of cognitive bias is the framing effect, demonstrated by Kahneman and Tversky in a 1981 paper.

In this experiment, students at Stanford and UBC were presented with a hypothetical situation and a choice between two options with equal outcomes:

Imagine the US is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual disease that’s expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. If program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved. If Program B is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that 600 people will be saved, and a 2/3 probability that no people will be saved. Which of the two programs would you favor?

Despite both options offering identical outcomes, a majority of students displayed a bias towards the “risk-averse” framing in option A.

Source: Vanity Fair

History of cognitive bias

Cognitive biases have been studied by psychologists, economists, and other researchers since the 1960s, when psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Amos Tversky established the heuristics and biases research program and performed a series of studies on biases – mostly at the University of Michigan.

Kahneman and Tversky’s program popularized the idea that decision-making, at least when uncertainty is involved, is not a primarily rational activity. Instead, when we make decisions about things we don’t know, we’re more likely to use a heuristic – hence the proliferation of cognitive biases across society.

The pair’s findings on systemic errors in decision-making were collected in a seminal 1974 paper published in the journal Science, and later expanded in the 1982 book of the same title – Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.

Since then, cognitive biases have become a central focus in the field of behavioral economics. But the heuristics and biases model of decision-making also has its critics.

Common counterarguments include the view that biases describe an overly pessimistic assessment of the average person’s decision-making ability.

Another critique of (the popularity of) explanations involving cognitive biases is that a desire to document biases in the lab has caused some researchers to develop a “bias towards biases,” in the way they design their experiments and draw conclusions.

Daniel Kahneman is now a Nobel Laureate, having won the prize in economics in 2002. Amos Tversky passed away in 1996.

Cognitive biases you might not have heard about

Alongside the popular biases mentioned so far there are many lesser-known cognitive biases you may not have heard of. Here are a few examples:

Idiosyncratic fit bias

This cognitive bias describes a preference for scenarios where we perceive an idiosyncratic fit – a sense that we are more suited to some product, brand, job, or scenario than other people.

Feeling that an object or situation particularly “fits” us can make that thing more appealing and prominent in our thoughts.

Endowment effect

The endowment effect is the tendency to value things more highly just because we own them.

Let’s say your parents are selling some of your cherished childhood toys on eBay. While they’re happy with the bids they’ve received for the items, the endowment effect might cause you to think the offers aren’t nearly high enough.

Perceived effort bias

Perceived effort bias describes our preference for tasks and activities that appear easier or less costly, even if that appearance doesn’t reflect the overall value of the task, or the actual effort required.

For example, a student given the choice between writing a single 1,000-word paper or four, 250-word papers is likely to opt for the short multiple exercises, despite both options requiring the same number of words.

Likewise, customers tend to be more motivated by sales copy that contains low-effort terms like “easy,” “simple,” or “in a single step,” and less motivated by high-effort terms like “please come back later” or “complete these ten steps.”

Examples and case studies

To better understand how cognitive biases can affect decision-making, let’s look at a few examples and case studies.

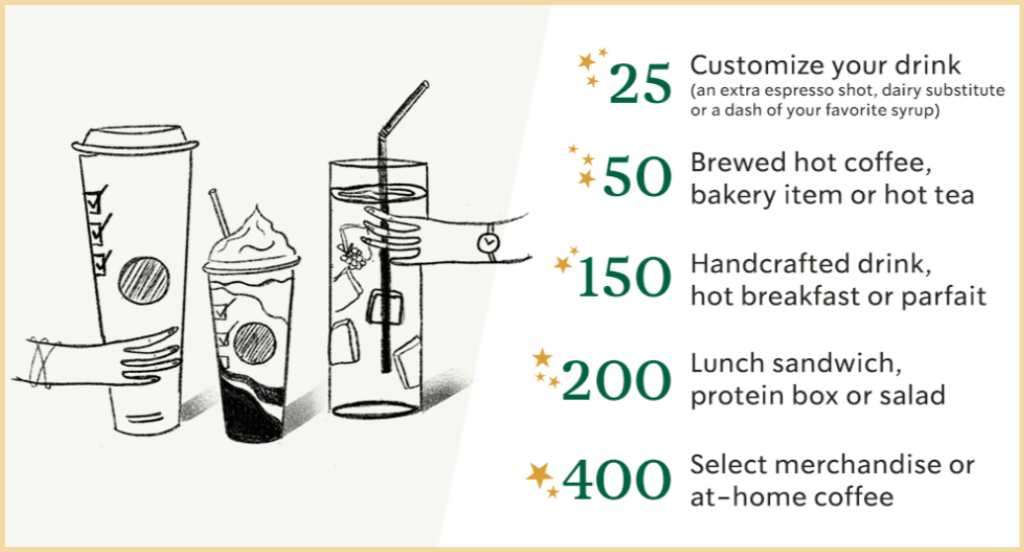

Source: Starbucks Stories

Brand loyalty programs

In business, the idiosyncratic fit bias can be seen in the way customers view loyalty programs.

According to a 2003 paper in the Journal of Marketing Research, consumers tend to judge the value of loyalty programs based on how hard they need to work to get rewards compared to the efforts of a typical customer.

When consumers believe they have an idiosyncratic fit with a loyalty program (and can therefore acquire rewards more easily than others), their assessment of a program tends to be more favorable.

The paper also claims that the effect is heightened when loyalty programs have higher entry requirements.

Source: InsideBE

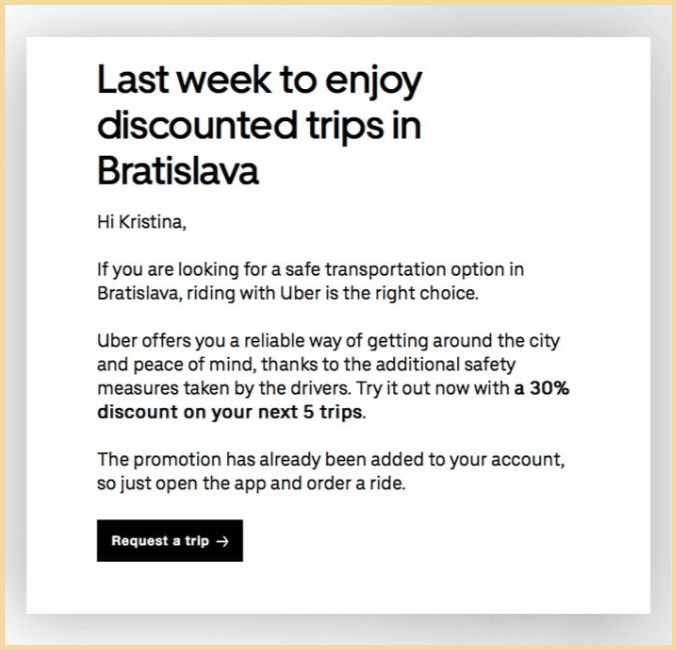

Uber discounts

Uber knows how to use the endowment effect to increase the uptake of their promotional discounts. In the example above, the copy is carefully worded to increase a sense of ownership.

Instead of just saying “Get a 30% discount on your next 5 trips,” Uber chooses to use the customer’s first name, mentions that the promotion “has already been added to [their] account,” and (once the app is opened) displays the discount as a visible promo code in their wallet.

These small additions make the customer feel like the discount is already theirs, instead of a generic item that they need to acquire and use. If customers feel like they own the discount, they will be more likely to utilize it.

Source: InsideBE

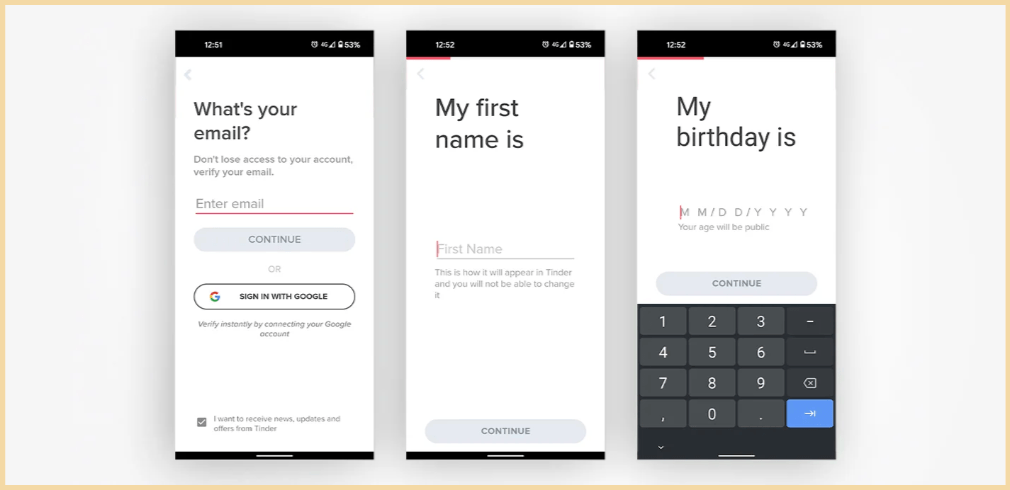

Signing up for Tinder

Apps usually need to collect data from new users in exchange for a service. However, if the onboarding process seems confusing or lengthy, customers are more likely to abandon it.

To reduce abandonment and improve user sentiment, Tinder targets perceived effort bias to make their sign-up process feel seamless.

Instead of showing customers a long list of profile questions to fill in, they place each task on a separate page, and include a progress bar running along the top of the screen.

While the effort required to complete the sign-up process is the same no matter how the questions are formatted, dividing them up and illustrating user progress makes the whole process more digestible.

Often, reducing perceived effort works because customers tend to feel more positively toward companies that regularly meet their expectations (by making interactions simple, efficient, and effective) than toward companies that aim to exceed their expectations (with perks, extras, and discounts).

Summary

What is cognitive bias?

A cognitive bias is a pattern of thinking that doesn’t track with rationality. Biases happen when our brains take mental shortcuts, called heuristics, to respond quickly in moments of uncertainty.

There are over 150 cognitive biases documented in academic literature.

What are some common types of cognitive bias?

- Anchoring bias: relying too much on the first piece of information you hear when making a decision.

- Confirmation bias: only paying attention to information that confirms existing beliefs.

- Representativeness bias: judging the probability of something happening based on how similar it is to something else.

- Availability bias: thinking something is more likely to happen because it’s more memorable.

- Framing effect: a bias towards information presented in risk-averse terms.

- Optimism bias: thinking positive events are more likely to happen and negative events are less likely to happen.

- Hindsight bias: believing that past events were more predictable than they actually were.

What impact do cognitive biases have?

In business, cognitive biases can be targeted by marketers to make brands more memorable and product deals seem like they offer better value.

For example, anchoring bias can be harnessed to make sale prices more attractive, or the framing effect can be used to change the way customers perceive product benefits.

In regular life, cognitive biases affect our daily opinions and actions, often to suboptimal outcomes.

For example, availability bias can cause us to focus on memorable, unlikely dangers like plane crashes or food poisoning, instead of more common dangers like car accidents or an unhealthy diet.