Chunking – Everything You Need to Know

Article content:

Definition of chunking

To define chunking, we need to take context into account. Even though it originated as a technique to improve memory recall, nowadays it’s used to do so much more.

For example, it can make complex decisions much easier and simplify the whole decision-making process. That’s what this article is mainly about.

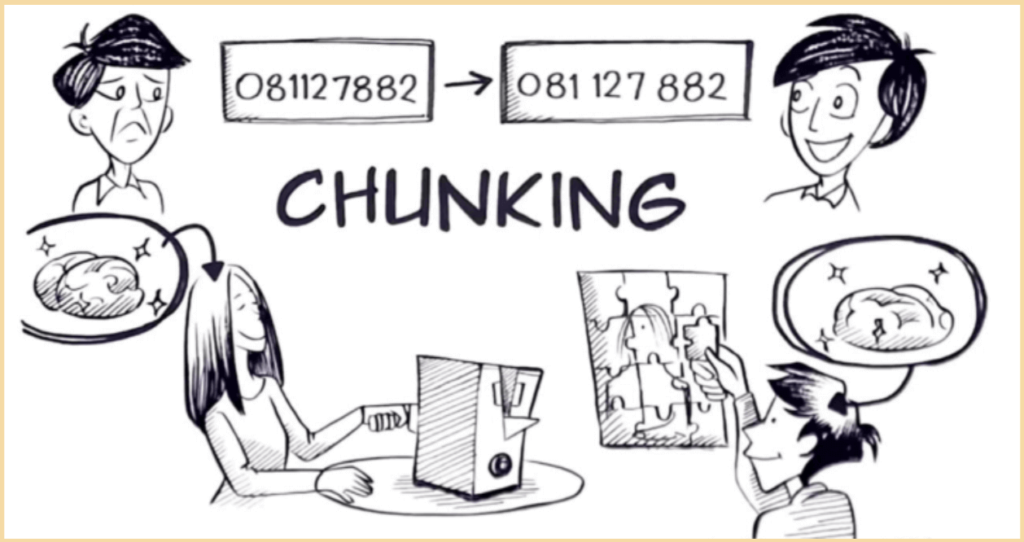

In essence, chunking can be defined as breaking complex information down into simpler and more digestible parts. These parts are easier to process, remember, and recall, with an emphasis on the processing part. More on that in a minute!

Source: Medium

How it works

The simplest example of how chunking works is in trying to process a string of numbers. Let’s try a simple experiment – you have 15 seconds to read this string of numbers and try to memorize it. Ready, set, go!

07466469421

Dividing the string into smaller parts taxes our brains way less.

Now, try to recall it. Not that easy, is it?

Let’s chunk the string into smaller pieces. Take another 15 seconds to memorize this:

07 446 469 421

How about now? Much easier, isn’t it? Dividing the string into smaller parts taxes our brains way less. Suddenly, you don’t need to remember 11 separate elements, but rather 4 little chunks.

Let’s get a bit more practical though. As you kick back on your couch after a long day at work, the last thing you want is to be overwhelmed by a thousand Netflix shows in random order. That would make it impossible for you to choose and would probably lead to you just scrolling Tik Tok for the next hour instead.

Netflix knows this and tries to chunk the selection into several categories right on the home screen – top picks for you, top 10 trending in your country, or critically acclaimed films. These are not just Netflix’s whims, but rather its effort to make it easier for you to choose.

The principle is the same – they chunk the big pile of information into smaller parts, so it’s objectively easier for you, the user, to make a decision.

Why it works

Everyone who has ever studied for an exam of any kind would confirm this – the brain has a limited capacity for how many things it can store at once. Regular mortals can usually only remember up to 7 things at a time.

This can be interpreted as a physical limitation – our brains simply cannot create strong enough neuronal connections.

So, when we face a complex decision we procrastinate. It seems like it will cost us a lot of time and energy to do it, so we would rather postpone it or not do it at all.

There are two streams of thought about why chunking works. The first one claims separate chunks take up less memory capacity and in a way, this is a form of data compression. It is basically a workaround – smaller pieces of information are easier to process and cost us less energy.

So, when we face a complex decision we procrastinate. It seems like it will cost us a lot of time and energy to do it, so we would rather postpone it or not do it at all. This cognitive bias is called perceived effort and it can drive customers away lightning-fast.

However, when we split such a decision into multiple smaller ones, it instantly seems more doable. One step at a time, as they say.

The second stream of thought applies more to just memory recall, as it says that chunking is based on redintegration. This basically means that the little pieces of information remind us of the whole. That’s why you think of the whole song when hearing just a few words.

The little pieces of information remind us of the whole. That's why you think of the whole song when hearing just a few words.

History of chunking

To learn how chunking came into being, we have to go way back to 1956. Harvard professor George Miller published an article called The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Information Processing. He made history without knowing it.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

In his experiment, besides other things, he tested people’s memory span. He presented them with a long list of items they had to remember and then tested how many items they actually were able to remember.

What Miller noticed was that people could recall between 5 and 9 items.

As he wanted to know how much information could be stored at once, he turned items into bits of information. For example, binary digits represented 1 bit each, decimal digits represented about 3.32 bits each, and words about 10 bits each.

What Miller noticed was that memory span was approximately the same for items that contained a different amount of information. People could remember around 7 items, but it could be seven words, seven decimal digits, or seven single digits. Even though they contained different amounts of bits, people were able to remember them.

Miller concluded that people's memory spans were not limited by the number of items, but rather by the number of chunks.

Miller concluded that people’s memory spans were not limited by the number of items, but rather by the number of chunks, hence the term “chunking”.

Since then, chunking has been widely used as more than just a memory booster. It very quickly became clear that “hacking” our processing capabilities can be beneficial for improving sales funnels, increasing sales, or improving CX. Let’s see some examples.

Chunking experiments

Meaningful chunks were easier to recall

In a classic experiment in 1966, Richard Lindley took a look at whether how meaningful chunks are can affect how easily they are remembered.

He presented participants with 18 trigrams (chunks of three letters) along with recoding cues. For example, a recoding cue for a trigram REH could be Rehearse. As this cue had the first three letters identical to the trigram, it allowed the trigram to be remembered in a meaningful way.

When chunks of letters were presented with a meaningful cue, participants associated the meaning with the chunks and were able to recall more of them.

However, some trigrams were paired with cues that were not that straightforward. For example, for the REH trigram, the less meaningful cue recoding cue could be Relent, which has only the first two letters in common.

The results were straightforward – when chunks of letters were presented with a meaningful cue, participants associated the meaning with the chunks and were able to recall more of them.

The author concluded that the meaningfulness of the chunks could even improve how easily it is processed.

Familiarity boosted the number of remembered chunks

In a well-known study, William Chase and Anders Ericsson studied the effect of the familiarity of chunks. Their hypothesis was that more familiar chunks could boost our memory capacity. What was interesting about this study, was that it only contained a single participant – “SF”.

After the authors practiced with SF for over two years in a total of 264 sessions, SF’s memory span had grown to 82 digits.

SF’s memory span was pretty normal at first – around 7 digits at once. However, as SF was a long-distance runner, he was able to chunk strings of digits into race times – units that were very familiar to him.

Until that time, the highest digit spans in the literature were around 20. After the authors practiced with SF for over two years in a total of 264 sessions, SF’s memory span had grown to 82 digits.

Examples and case studies

Chunking a menu increased the average spend per head

Cowry Consulting was approached by the restaurant chain Mitchells & Butlers with a clear task – to increase the average spend per head by 4 pence. What Cowry managed to do was to go way beyond that. How did they do it?

With a simple menu redesign. Besides other things, they found the menu to be overwhelming – there were too many options, which made it harder to choose.

They reduced the number of options and chunked them into straightforward categories – Meat, Steaks, Vegetarian & Vegan, and Fish, to make it easier for customers to choose.

Source: Cowry Consulting

They also improved the chunks themselves and gave equal space to the mains, starters, and desserts, so that customers would actually pay attention to more than just the mains.

These small changes in the menu increased the average spend not by 4 pence, but by 13!

Creating categories for wines made it easier for customers to choose

Best Cellars, the 2009 Wine Enthusiast’s Retailer of the Year, decided to make the wine selection process easier for its customers. They limited the selection to 100 high-quality, reasonably priced wines.

But 100 wines could still be an overwhelming number, especially for someone who doesn’t know their way around wines.

That’s why Best Cellars pushed even further and divided their wines into nine simple categories, such as “wines under $30”, “Champagne & Sparkling wine” or “aperitifs/spirits/digestives.” An inexperienced wine seeker now had only a few categories to deal with, which could be managed fairly easily.

Once they’d chosen a category, it was easier to navigate the remaining options by reading the bottle labels.

Ogilvy increased medication adherence by 21%

Imagine you’re a doctor who wants to increase medication adherence. You know that taking a pill daily can be challenging and something that is easy to forget, especially considering the busy lives of your patients.

Ogilvy used chunking and divided the pills into 3 bottles of 7 pills. The bottles were each in different colors. This simplified the whole process and made it easier to follow.

The design of the medication is not helpful either. The whole package of antibiotics consists of 21 pills (way over the magic 7 +/- 2). If, however, you had partnered up with Ogilvy Consulting, you would’ve seen a simple change leading to a 21% increase in adherence.

Ogilvy used chunking and divided the pills into 3 bottles of 7 pills. The bottles were each in different colors. This simplified the whole process and made it easier to follow. Patients first opened the green bottle, then the red one, and then the orange one. All of a sudden, the task didn’t seem so unattainable anymore.

How to use chunking in business

Split choices into categories

When selling a product, the easiest thing you can do to make it easier is to chunk it into categories, similar to Best Cellars or Netflix.

The streaming giant doesn’t list all its titles from A to Z. Choosing from a list of thousands is overwhelming, but picking from a few movies within a certain category can be less daunting.

Reducing the amount of information we have to process helps us to make faster decisions. So chunking down a seemingly infinite number of titles into a comprehensive and finite number of categories is a good strategy.

What’s more, studies show that choosing from a categorized list, as opposed to an uncategorized one, makes us happier with our decision! A study conducted at Stanford University found that consumers like unfamiliar products to be categorized – even if the categories are meaningless.

People were happier with their choice of coffee if it came from a categorized selection. It didn’t matter whether they were marked simply A, B, and C, or had more meaningful tags such as “mild”, “dark roast” and “nutty.”

Split the process to boost your funnel conversions

This one has a lot to do with the perceived effort mentioned earlier – the fact that how hard something seems to do is even more important than how hard it objectively is to do. In other words, if something feels like a hassle, we tend to avoid it.

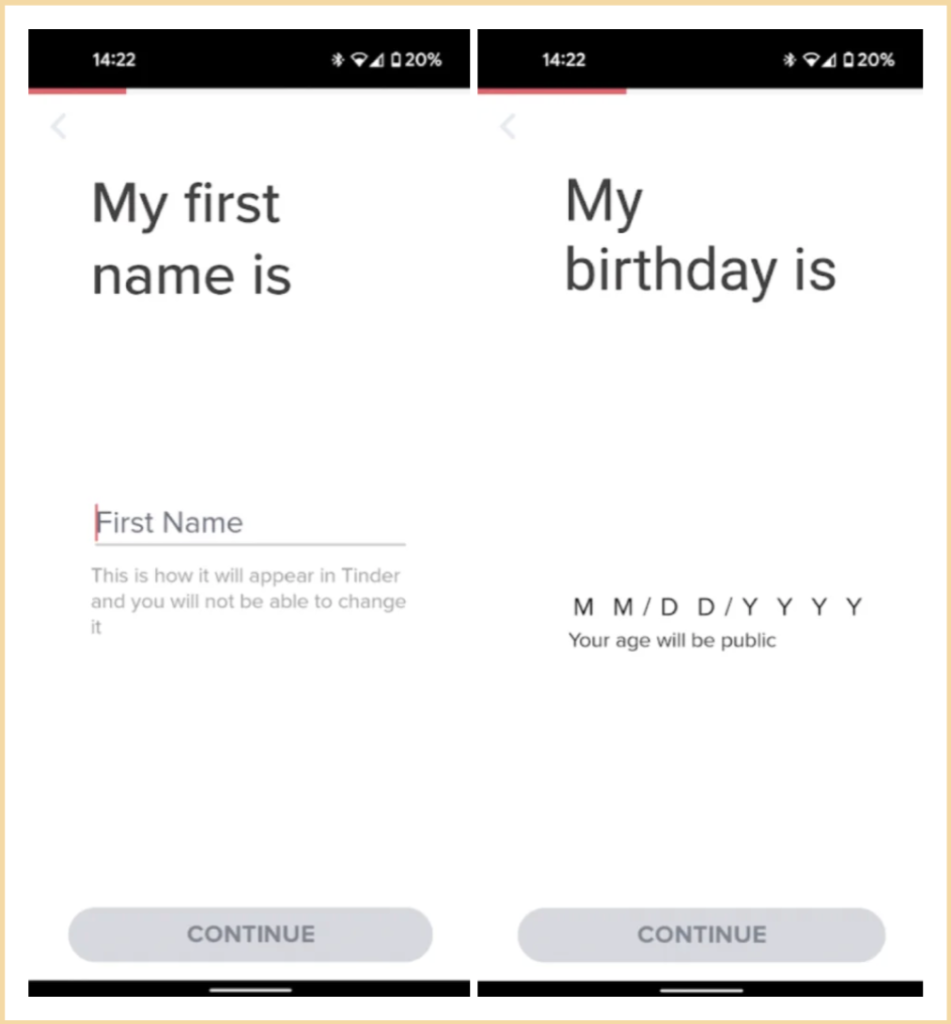

However, if you’ve ever tried to find a partner via Tinder, you might have noticed how easy it was. Or, at least how easy it was to register on Tinder.

When asking for age, Tinder could remove uncertainties a little better.

Source: Tinder

Tinder lowers the perceived effort perfectly by simply chunking the registration process into multiple smaller parts. What they do is, they ask you a single question at a time.

It’s much more efficient than if they asked 12 questions on a single screen. This would look like a lot of work to fill in right away and might drive clients away. But a single question? I can do that!

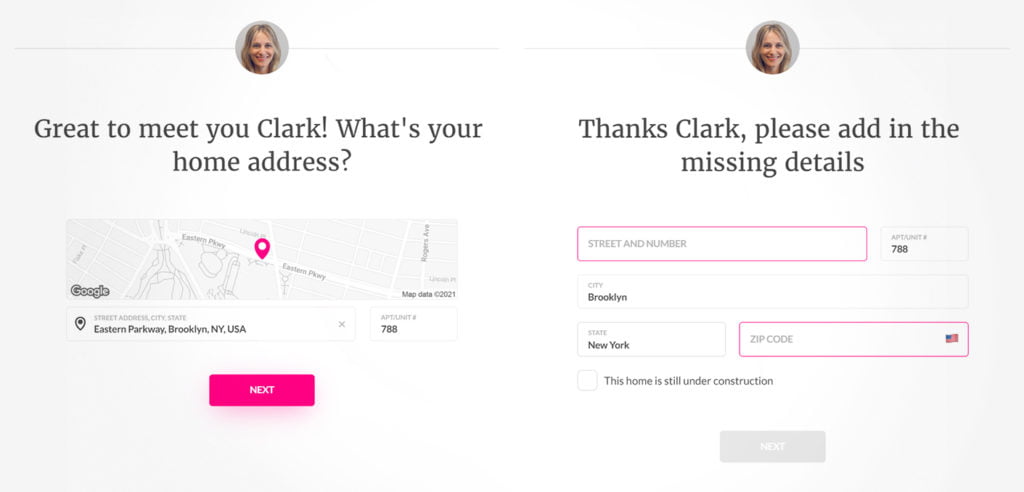

Lemonade, an insurance company, does exactly the same thing – they ask for a single piece of information per screen.

Source: Lemonade

The bottom line is, simplify your online funnel. Don’t ask too many questions at once, chunk them into multiple smaller steps. It will be much easier this way than filling out endless forms.

To push it even further, you can show the customers a progress bar to give them a sense of where they are in the process and approximately how long it will take to complete it.

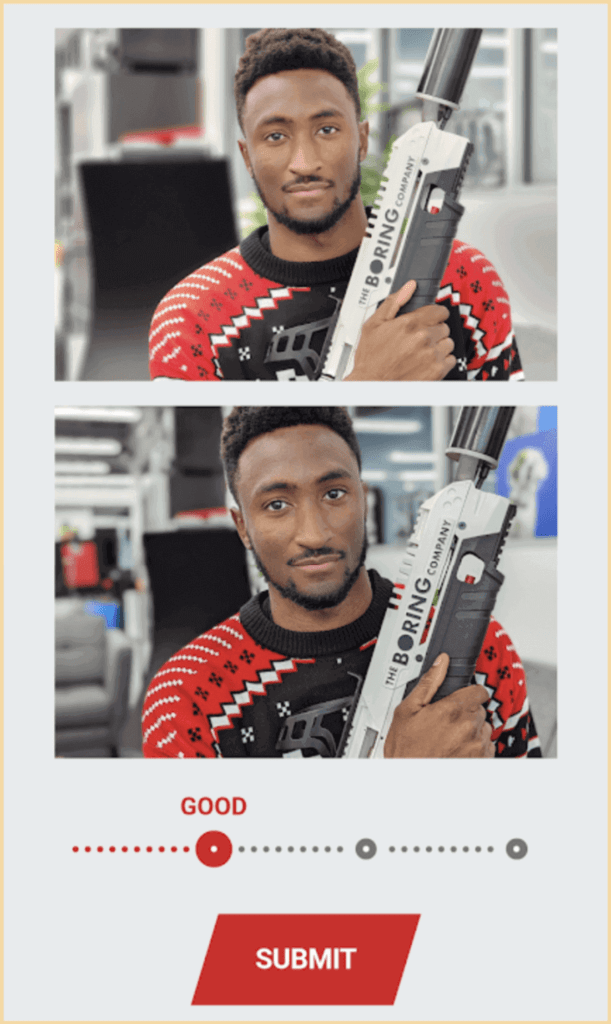

Recently, the biggest tech YouTuber Marques Brownlee asked his fans to participate in his annual blind smartphone camera test. They were asked to vote on which photos they liked more and make dozens of photo comparisons. The more comparisons they made, the more accurate the final results would be.

It took a while! But what was really helpful for voters was the progress bar that not only showed them where they were in the process, but also how helpful their participation was.

Summary

What is chunking?

In general, chunking refers to splitting a large portion of information into smaller pieces. This way, people can process the information easier, which allows them to remember more of it.

Also, the easier the information is to process, the easier it is for people to make a decision.

Why does it work?

Chunking allows us to partially overcome the physical limitations of our brains – it’s a form of data compression. For example, instead of processing 12 numbers, we can split it into 4 chunks by 3 numbers, which allows us to process 4 pieces of information instead of 12 separate digits.

Chunking also lowers the perceived effort. When we’re about to pick from several options, chunking it into categories makes it seem like less of a hassle.

How to use it in business?

There are two easy ways to use chunking in business:

- Splitting choices into categories: This makes the decision seem easier to do and increases the chance of customers actually deciding.

- Splitting the process: When asking customers for information, don’t ask for it all at once. Instead, split online forms into multiple screens, each asking a few questions. Nobody likes long forms, but everyone can answer one or two questions per screen.