The Peak-End Rule – Everything You Need to Know

Article content:

Definition of the peak-end rule

The peak-end rule is a psychological heuristic we use to simplify remembering. When looking in retrospect, our minds are not judging an experience as a whole. Instead, they highlight the memories that come to mind the easiest and make judgments based on those.

Most of the time, it is firstly the emotional peak of the experience – whether negative or positive – that is underlined by the strongest emotions, and thus is easier to remember, and secondly, the end – the most recent, and thus the most available part of an experience.

To get a better feel for how that works, consider this: What would you say if I asked you to tell me about the best amusement park you have ever been to?

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

You might describe a great ride – a roller coaster that blew your socks off. Or maybe you would tell me a sad story of how, after waiting in line for over an hour, the ride closed before you reached the front. And of course, you wouldn’t miss out that moment when, just before leaving, you got great pictures from the photographer.

But you wouldn’t tell me everything.

You wouldn’t describe waiting in line or getting an average plate of fries at the food stall. You wouldn’t mention most of the rides – not because they were not worth mentioning, but because of how our brains perceive and remember experiences – because of the peak-end rule.

How does it work?

Why do we remember events through the peak and the end?

Memories did not evolve to catalog everything that happens. Instead, they are an evolutionary “survival handbook”.

The peak-end approach to remembering has developed over eons to save on the “computing power” of your brain. According to world-renowned expert on human behavior, Daniel Kahneman, memories did not evolve to catalog everything that happens. Instead, they are an evolutionary “survival handbook”, storing only what is important to keep you alive and safe.

If your ancestor was jumped on by an alligator while trying to drink from a river, she needed to remember two things to avoid making the same mistake again:

- the stress and fear of being jumped on by an alligator (the emotion)

- surviving by grabbing the first branch and getting up in the treetops (the end)

Valuable experiences that might save her life in future got compressed into an emotional peak and a fortunate end, containing the action leading to it.

And even though we might not run away from alligators nearly as much as our ancestors used to, the way we remember hasn’t changed a bit.

Why do we remember emotional peaks?

Emotions act as a kind of highlighter of important memories – we tend to remember them more than non-emotional ones.

Most people are not emotional about the brand of bread they buy, or the road they take to work every day. These memories are recurring and expendable and that’s why they will mellow out more easily.

In contrast, if you are emotional about something it is most likely important to you.

It might be something remarkably enjoyable, cute, dangerous, or even life-threatening. A drive home from work is ordinary only up to a point where you get a flat tire at full speed and manage to keep the car on the road only by sheer force of will.

The fear for your life and the fury at some irresponsible idiot who broke a glass bottle in the middle of the road transforms this memory from an “ordinary” file into a “survival guide” file in your brain.

One interesting effect of emotional experiences is that they also tend to become representative in our minds, even though they are at the extreme end of the spectrum.

One interesting effect of emotional experiences is that they also tend to become representative in our minds, even though they are at the extreme end of the spectrum.

Next time you think about the dangers of driving, broken glass on the road will come into your mind as a significant one – even though it is a much rarer cause of crashes than drunk driving or texting.

Why making a memorable end enhances customer experience

Each experience consists of events stacked one on top of another. If you go shopping, first you take your shopping cart, then you go inside. You search and compare products, go through different sections, and then in the end, go through the check-out.

After you leave the shop, the checkout will be your “freshest” memory of the shopping process. If you had to wait in line for a long time, the negative emotion that entails is what will be at the top of the stack after you leave – and it will color the whole experience as quite a negative one.

On the other hand, if you are handed a free gift at the checkout – even something small like a plushie or a coloring book – the final moments before leaving will be vastly more positive. And they will be the most available memories when thinking back on the experience.

Peak-end rule experiments

Most of the defining experiments on the topic of the peak-end rule can be attributed to Daniel Kahneman. In the 90’s, Kahneman focused heavily on hedonic psychology – the study of what makes experiences pleasant or unpleasant – in experiments like these:

The length of an experience does not matter – the “Movies” experiment

In one of the earliest experiments, Daniel Kahneman and Barbara Fredrickson showed a group of test subjects a set of pointless movies. They varied from pleasant (penguins at play) to really aversive ones (amputation). Each movie had a short version, as well as an extended, three times longer version.

Two groups were shown movies with randomly selected lengths of clips: One was encouraged to rate the movies throughout. The other group was just asked to watch.

When evaluating something in hindsight, the length of the experience does not matter as much – it's the emotional high point that we use as an anchor to rate the experience.

After seeing all of the movies, both groups were asked to rate the movies from memory.

Interestingly, there was little to no difference in variables between being shown shorter or longer clips or being informed about the evaluation in advance vs. not being informed.

What really altered the ratings was the peak scene of the movie and its ending.

Most people rated the whole movie based on the most pleasant or unpleasant moment and the ending of the movie. And they gave a similar rating no matter the circumstances.

This experiment proved one of the basic ideas behind the peak-end rule.

When evaluating something in hindsight, the length of the experience does not matter as much – it’s the emotional high point that we use as an anchor to rate the experience.

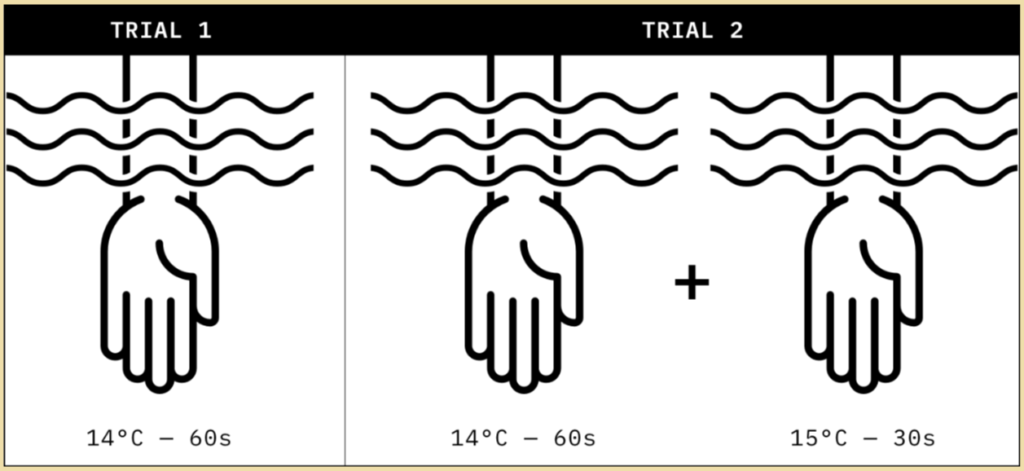

More pain is better – the cold water experiment

In his second and more famous experiment in 1993, Kahneman subjected people to two aversive experiences.

First, people were asked to dip their hand into 14°C water for 60 seconds. After that, they dipped their hand into the same 14°C water for 60 seconds, but after the time limit, kept their hand submerged 30 seconds longer.

During that time the water was gradually heated to 15°C – still painful, but more tolerable for most people.

Source: UX Collective

Sometime after the experiment, people were asked which procedure they would like to repeat – and most people chose the second option. They actively chose more pain and longer suffering, just because it was more pleasant in the end.

This again proved that the length of experience does not matter. The more pleasant ending was remembered, while the rest of the details were forgotten.

Retrospection is a pain in the butt – the colonoscopy experiment

Kahneman, together with Redelmeier, continued with another experiment later that year, this time in a medical setting.

Studying patients undergoing a colonoscopy (which took anywhere from 4 to nearly 70 minutes), subjects were asked to rate their experience each minute. After a month, they were asked to rate the pain of the procedure – and again, ratings from the most painful moment of the procedure as well as the end gave a pretty accurate prediction of their overall rating.

Patients for whom the experience ended “just” unpleasantly rated the whole examination much better than those whose examination ended directly after the painful procedure.

A few years later, in 1996, they repeated the experiment with a slight change. For one group of patients, at the end of the procedure, they left the tube inside for 3 minutes before extracting it. That is uncomfortable, but a great improvement over the painful examination itself.

Again, patients were asked to rate their experience a month later. And lo and behold – patients for whom the experience ended “just” unpleasantly rated the whole examination much better than those whose examination ended directly after the painful procedure.

And not just that – thanks to remembering the less painful part, the patients were more likely to return for further procedures.

History of the peak-end rule

The theory of the peak-and-end system of experience evaluation was pioneered by Daniel Kahneman in the early 90s. Although there had been several studies dealing with a similar theme earlier (Kent, 1985; Rachman & Eyrl, 1989; Thomas & Diener, 1990), Kahneman’s research paved the way for the peak-end rule as described in his study “When More Pain Is Preferred to Less: Adding a Better End” from 1993 (the one with the cold water experiment).

Since then, there have been multiple studies confirming the concept.

The peak-end rule also applies to goods and pleasurable experiences, and that the ending of a pleasurable experience has a significant impact on perceived happiness afterwards.

A 2008 study from Amy M. Do confirmed that the peak-end rule also applies to goods and pleasurable experiences, and that the ending of a pleasurable experience has a significant impact on perceived happiness afterwards.

More recently, a study by Vincent Hoogerheide from 2018 explored the effect of the peak-end rule on the peer assessment of children in class. Children preferred negative feedback, even if it was longer but softened at the end by a less negative point. On the same note, they remembered the positive feedback that did not end on a less positive note as better.

Of course, there are also skeptics, who mostly divide into 3 categories:

- Firstly, there are studies suggesting the framework is overly simplistic and leans too much on controlled studies in a lab environment.

- Secondly, most of the existing studies have sought to confirm the rule, and did not research other possible predictors.

- And finally, there is a major fall in the effect’s significance over the long term – as demonstrated in a study by Geng et al.

Examples and case studies

Peak-end masters: How Disneyland makes you love your visit

Staying at Disneyland is one of their most memorable experiences for many people – children and adults alike. People travel from all over the world just to see Mickey, ride the rides … and that’s not just a happy coincidence. The Disneyland experience is carefully crafted with the help of scientists as well as creatives.

Source: Mickey visit

To maximize peaks and provide many distinct high points when looking back, Disney makes sure you have keepsakes from all the best experiences you had. Photographers standing all around the park take photos of you and send them to your app, where you can keep the ones you like the most.

When looking back, photographs strengthen the good feelings you have about the park – because they reinforce the positive peaks of the stay in your memories.

When looking back, photographs strengthen the good feelings you have about the park – because they reinforce the positive peaks of the stay in your memories.

And to cement these good memories, there’s a really powerful end to every Disneyland visit.

Just before the park closes at 10 p.m. there is a 9 p.m. grand Disneyland Forever show with fireworks and visual effects, ending with a “Kiss Goodnight” music/storytelling piece.

This heartwarming farewell from the land of magic will stay with you for a long time – as it is both emotional, and your last memory of the whole experience.

Want to learn more behavioral tricks Disney uses to make your visit pleasurable? Read about how they make waits bearable and lines seem shorter in our case study on customer experience at Disneyland below.

All’s well that ends well: How Standard Life increased customer satisfaction with a single question

The life assurance, pensions and savings company Standard Life asked behavioral psychology experts from Cowry Consulting to redesign the script their customer support was using when communicating with customers. Changing one question at the end of the call, together with two other changes, led to a 13% increase in customer satisfaction.

The standard end of a call went something like this:

- “Now that we’ve dealt with your inquiry, is there anything else I can help you with today?”

The customer says no.

- “Would you like to take part in our survey about the quality of service you received?”

The customer says no, finishing with a double negative.

This double negative was the “end” that got wrapped around the memory of the whole experience when they were later asked to rate the help they had received – and lowered the overall satisfaction.

When the script for customer support was rewritten, and instead instructed people to ask: “Have we covered everything you needed from us today?” people were not just more likely to answer yes to a subsequent request to fill out the survey – they also felt better about the whole interaction in retrospect.

Find out two more principles used to improve on the script that increased customer satisfaction from 67 to 80% … and increased sales by as much as 54.5%.

How can you use it in business?

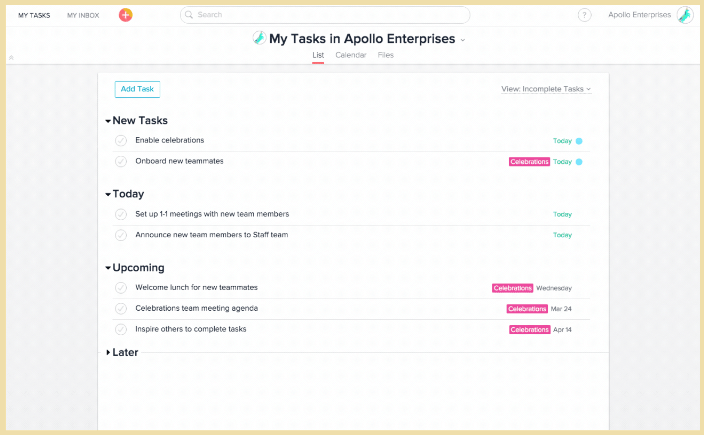

Build up the positive peak with encouragement

Even trivial things like a positive encouragement or a little praise can create a positive peak – or smooth over a negative one.

This idea is abundantly used in the UI of digital products.

Take a look at how Asana – the project management platform – celebrates the completion of assigned tasks.

Source: Asana

One of 4 mythical animals (a yeti, unicorn, narwhal, or phoenix) will briefly pop up on your screen when you finally tick off that task you have been working on for the last few hours.

You are flooded with endorphins from completing the task, and Asana underlines this emotional peak of the process through a simple animated animal – enough to make you smile and feel just a tad better.

You are flooded with endorphins from completing the task, and Asana underlines this emotional peak of the process through a simple animated animal – enough to make you smile and feel just a tad better.

A similar UX trick is used by another SaaS platform – MailChimp. After you have gone through the quite complicated – and in most situations important – process of setting up your email campaign, the painstaking angst of “what have I forgotten?” is eased by a simple animation of a chimpanzee (the company mascot) hovering over the big red “send” button.

If you wait long enough, the hand will even start to sweat and create a little puddle, cracking a little fun at the expense of your nervousness.

The peak-end rule affects how customers think about price

In a study from 2008 on dynamic pricing, Javad Nasiry and Ioana Popescu found that the standard model of how customers perceive prices is not quite right.

If you are selling pencils for example, you might think that people judge if your wares are too expensive by the price over the long term. So, if your prices gradually increase, people will just deal with it, and it will not have an effect.

But that was in fact disproven – price perception also follows the peak-end rule. Customers anchor on the lowest price they can remember and compare it with the most recent price they paid for a similar product to judge if your offer is too expensive.

According to this research, big sales with high discounts can actually hurt sales in the long run – because the discounted price will become anchored as a “peak” price for your products. When prices return to normal, customers will be more reluctant to buy and will feel less happy with their purchase.

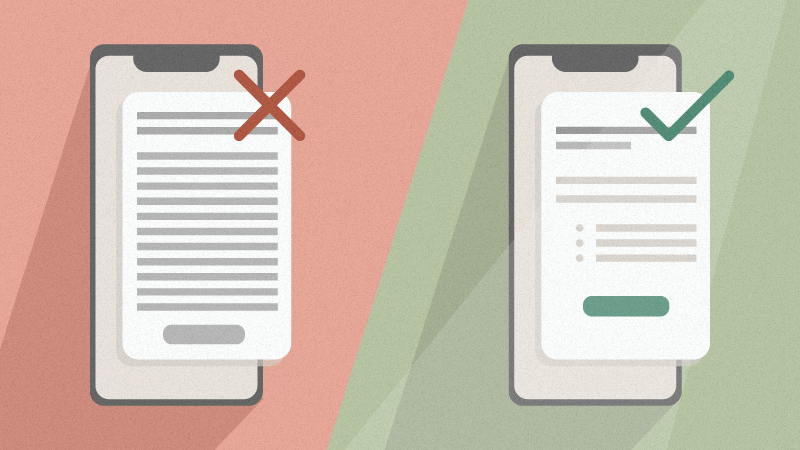

Create the least painful checkout experience

Nearly 70% of customers leave just after hitting the checkout page of an e-shop.

Hint: they don’t leave because the experience was unbearably good. Most of the time, there was something that pushed them away even though they were ready to buy!

The checkout process is inherently difficult. It asks you to part with your hard-earned money, requires you to put in a lot of personal data … and a simple resolution of this painful experience is just one click on the X away.

You can make it an emotional high point. Offer customers a free gift just before they pay in order to sweeten the deal or give them a discount on a future purchase.

But if you can’t make it positive, at least make sure the checkout is the least negative part of their experience.

- Give an optional, non-registration checkout option.

- Pre-fill the lines on the order.

- Don’t add extra costs your customers didn’t know about beforehand.

- Make sure the whole checkout is as fast and streamlined as possible.

Customer support can also play a significant role in the checkout – if your customer is having trouble finishing the order, you can offer them a free consultation with an agent to help them out.

All of this extra care and seamlessness will make the “painful” checkout much more bearable and make it more likely to stand out as a positive point in retrospect.

Summary

What is the peak-end rule?

The peak-end rule is a psychological shortcut we use to simplify remembering. When looking in retrospect, our minds are not judging experiences as a whole. Instead, they highlight memories that come to mind the easiest, and judge based on those. Most of the time that is the most emotional point (positive or negative) and the end of an experience (the most recent part).

Why is it important?

When crafting customer experiences – be it serving a meal in a restaurant or a whole day in an amusement park – we should think in a framework of experience peaks and memorable ends. Most of the experience can be mediocre – but if the highest point is a real banger, and the end is as pleasurable as possible, people will love the memory.

How can you use it in business?

- Be mindful of the checkout – the checkout is the end of our shopping experience. Making it streamlined and even adding a pleasant surprise gift at the end can make it a high point of the whole transaction.

- Manage prices carefully – the peak-end rule also applies to price perception. The peak is the lowest price the customer remembers, and the end is the most recent price they bought something for. If the difference is too big, they will be less happy with the transaction.

- Encourage them to build a positive peak – find out the difficult or crucial points in using your product and spice them up with some clever UX. Simple animations or sound notifications can amplify the positive feeling of finishing a difficult task.