Heuristics – Everything You Need to Know

Article content:

Definition of a heuristic

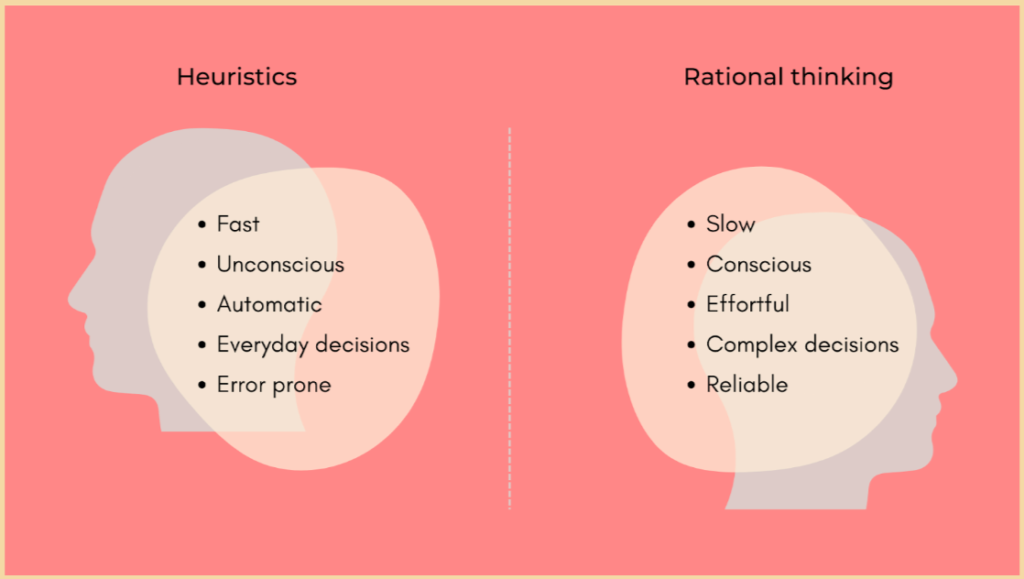

Heuristics are fast, efficient, general methods for making decisions.

Heuristics reduce cognitive load, simplify choices, and allow us to act quickly instead of needing to consciously think about all the options.

But heuristics can also generate inaccurate conclusions and irrational actions. In this way, they frequently lead to biases – irrational, often unconscious, influences on behavior.

In everyday life, you might call heuristics rules of thumb, useful tricks, and habits, educated guesses, or just plain old common sense.

How do heuristics work?

Heuristics form over time – developed by your own brain and by evolution – often in response to past experiences or folk knowledge.

As you make decisions and see their outcomes, your brain constructs frameworks to help you deal with similar events in the future.

If you encounter a situation that seems related to a previous experience, this framework will help you quickly form an opinion, answer, or prediction without spending as much time or mental energy on deciding how to act.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

How heuristics work in everyday life

We often use heuristics for smaller, commonplace decisions, where the stakes are low and time is of the essence. That means there are loads of everyday examples of them.

- For example, when shopping for sneakers, you might choose a pair that you’ve seen lots of other people wearing.

- Perhaps you decide that your new accountant must be good at their job because they’re punctual and wear a tie.

- Or, maybe you feel that your 10K run was a good achievement because you heard that most people your age can only run 8K.

These examples represent three of the most common types of heuristics – the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, and the anchoring heuristic. More on those in the next sections.

How heuristics work in business

Heuristics also play out in professional environments – both in how we work and how customers interact with marketing.

Tight deadlines, high stress, or simply a lack of accessible information can cause employees to fall back on heuristic-based decision-making.

For example, a rushed doctor may suspect a certain diagnosis based on a snap judgment about a patient’s profile and behavior, instead of (or hopefully alongside!) a detailed analysis of their chart.

Marketers can encourage customers to make heuristic-based decisions by framing information and making the choice to buy a product seem more straightforward.

Marketers can encourage customers to make heuristic-based decisions by framing information and making the choice to buy a product seem more straightforward.

For example, demonstrating that a product is popular or well-reviewed can act as a mental shortcut for product desirability or quality.

Why heuristics work

Heuristics work because they’re likely to be correct, on average. While there’s no guarantee that a heuristic-based decision will pay off in any given situation, overall, they are strategically advantageous behaviors.

The time-saving and efficient nature of heuristics can also be beneficial in certain situations, and helps people to avoid choice paralysis.

In this sense, heuristics aren’t good or bad in themselves. Instead, they’re a more or less appropriate form of decision-making depending upon the situation.

In this sense, heuristics aren’t good or bad in themselves. Instead, they’re a more or less appropriate form of decision-making depending upon the situation.

Using that “trick” you developed to improve your golf swing, or wearing your go-to outfit for making a good impression, may result in beneficial outcomes most of the time.

But over-trusting home remedies, general rules, or half-related experiences may stop us from noticing important details and thinking logically about the present situation.

History

In behavioral science, the term heuristics was first used around five decades ago. The history of the term is closely linked with psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, whose joint decades of research form much of how we now understand heuristics, as well as other forms of decision-making.

One of Kahneman and Tversky’s first joint papers identifies three of the most common heuristics used in daily life: these are the availability heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, and the anchoring and adjustment heuristic.

Heuristics experiments

Source: Kent Hendricks

Availability heuristic

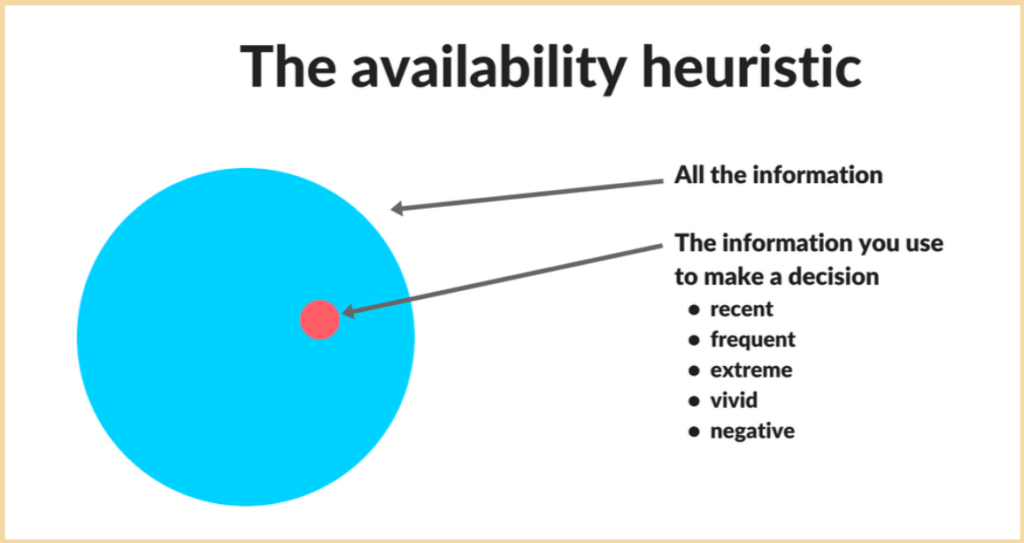

The availability heuristic describes how known information can have a greater bearing on our thought processes.

Vivid memories, scary news stories, past experiences, and the way that situations are framed can cause us to prioritize particular facts – even if there’s no rational justification for doing so.

For example, many people hold the irrational belief that air travel is more dangerous than travel by car.

High-profile news about plane crashes, vivid memories of feeling scared on planes – and conversely, a lack of available or interesting information about the relative safety of car travel – can trigger the availability heuristic, leading to inaccurate conclusions.

Tversky and Kahneman demonstrated the availability heuristic in a 1973 study using the letter “K.” They asked participants to decide whether it’s more likely that a random word will begin with the letter K, or that K will be its third letter.

While there are far more words with K as the third letter than the first, most people find it easier to recall words that begin with K. As a result, the availability heuristic caused participants to respond with inaccurate answers.

Representativeness heuristic

The representativeness heuristic describes our tendency to label and group events into categories, forming prototypes or expectations.

When we spot similarities between a current event and a previous experience, we’re disposed to draw parallels between them, even if the evidence for doing so is shaky.

For example, you might have a good friend who was born in a particular region of Spain. If you meet someone at a party who also happens to have been born in that same region, you might assume that you’ll get along well and feel positively toward them – even though you know nothing about them.

The representativeness heuristic can also result in negative associations or stereotyping. Profiling can be caused by the inappropriate deployment of heuristics.

Another 1973 paper by Tversky and Kahneman demonstrated the representativeness heuristic, by asking participants to make judgments about a fictional character, “Tom W.”

Participants were told that “Tom W is of high intelligence, although lacking in true creativity. He has a need for order and clarity, and for neat and tidy systems in which every detail finds its appropriate place,” among other descriptors.

Then, they were asked to rank nine graduate programs by how likely they believed it was that Tom W. was enrolled in them.

A logical response to the question might take some notice of Tom W.’s personality description, but would mainly focus on the overall popularity of each graduate program – meaning that Tom W. is most likely to be enrolled in the most popular program in the list, “humanities.”

However, participants ranked less popular programs like “computer sciences” or “engineering” as more likely. According to Tversky and Kahneman, this shows how the representativeness heuristic causes us to overvalue mental labels and categories and undervalue base rate data.

Source: Mental Model Minute

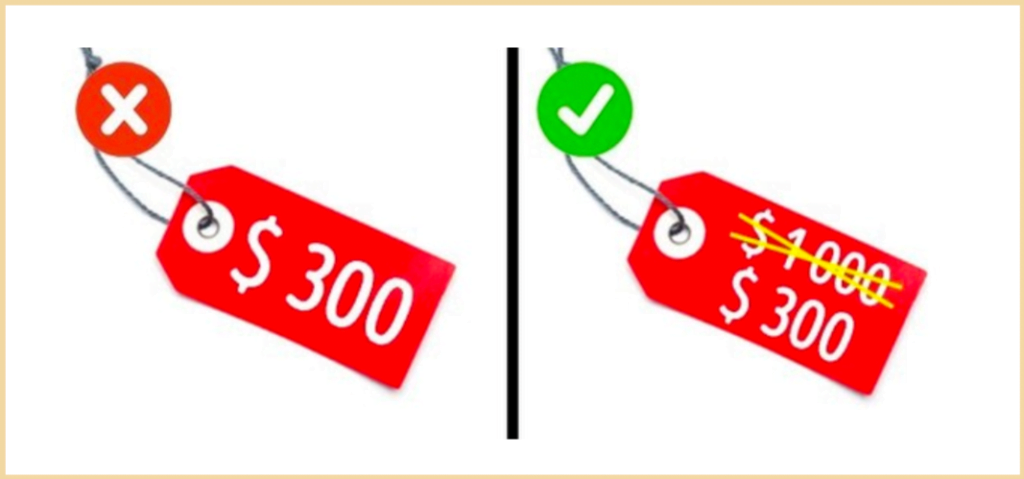

Anchoring heuristic

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic describes how we often estimate value by setting a ballpark figure (or “anchor”) and then fine tune our estimate in relation to that anchor.

For example, retail labels on discounted products often show customers how much the product previously cost. Seeing the difference between the “real” or anchor price and the current price can make the deal seem more favorable.

While the anchoring heuristic can yield helpful results, choosing inaccurate or irrelevant anchors can cause our estimations to become distorted.

Kahneman and Tversky showed this effect by asking participants to “estimate the number of African countries in the United Nations (UN).”

Before making their estimations, participants spun a number wheel to produce a random number between 1 and 100. Those who received a lower random number tended to guess that fewer African countries were UN members – showing the power of anchors, even when they’re demonstrably meaningless.

The 4 most common biases resulting from heuristics

When heuristics are inappropriately applied, they can cause irrational beliefs and behaviors based on an incomplete understanding of the situation – otherwise known as biases.

Four types of bias are commonly associated with heuristics. These are loss aversion, social norms, ambiguity aversion, and status quo preference.

Loss aversion

The vivid experience of losing possessions, or the emotions associated with failure, can play into the availability heuristic and trigger loss aversion.

This bias describes how we tend to favor actions that avoid losses over those which produce equivalent gains. The psychological significance of losses can give them greater weight in our mental calculations, even when logic says that decisions which include incurring a loss may lead to a better overall outcome.

Social norms

A social norm is a tacit cultural rule describing appropriate behavior in certain situations. Following social norms helps individuals conform to groups. Heuristics may increase our willingness to follow social norms and conventions, as we see others perform similar actions around us and accept them as best practices.

Ambiguity aversion

Uncertainty is another salient feeling we often focus on during decision-making, which can lead to biased thinking. Ambiguity aversion describes this irrational tendency, where unknown options are discounted in favor of known outcomes, even when there’s no logical case to do so.

Like loss aversion, ambiguity aversion can cause us to select less desirable options simply because we prefer to feel like we know what’s going to happen.

Status quo bias

Status quo bias is the subconscious preference for current or default options, regardless of their relative value. The systems, products, or practices that we currently use, or those considered “standard”, can become anchors in our minds, imbuing them with extra unwarranted significance during mental deliberations.

Next, let’s illustrate each of these biases with a case study.

Examples and case studies

Here’s how heuristic-based biases can play out in real situations.

Spotify

Spotify’s tiered subscription system harnesses loss aversion to encourage users into their premium program.

The streaming company regularly offers users on their Basic plan a free trial of their Premium subscription. The trial activates seamlessly, allowing listeners to take advantage of extra features without any interruption.

As the free trial continues, users become habituated to the premium features, to the point where they begin to see them as the default setup, and the idea of losing them becomes more costly than continuing to pay for the premium service.

Job searches & social proof

When recruitment site Job Angels and consultancy Mindworx wanted to increase candidate responses to job postings, they focused on users’ tendency to follow social norms.

Adding information about how many other people had seen and/or applied to a job posting caused users to feel that applying for that job was the socially expected behavior. Encouraging social norms generated a 138% increase in applications on the Job Angels site.

Zara

Online shopping contains many opportunities for customers to experience distraction, choice overload, or uncertainty. For example, if a customer can’t decide which size of an item of clothing to order, they may succumb to ambiguity aversion and leave the sales funnel.

ZARA reduced ambiguity for their online customers by designing a sizing tool that doesn’t require users to consider unknowns. Their 5-step process lets customers choose the right size without having to enter detailed information or measure themselves.

New Coke

The famously disastrous attempt to reinvent Coca-Cola’s soda recipe in the 80s is a great example of the status quo bias. The development of New Coke included many rounds of blind taste testing, in which participants consistently preferred the new recipe over traditional coke.

In practice, however, customers widely rejected the revamped drink. Why? Because the introduction of New Coke triggered status quo bias, which weighted the battle in favor of the traditional Coke recipe that people were already familiar with.

The introduction of New Coke triggered status quo bias, which weighted the battle in favor of the traditional Coke recipe that people were already familiar with.

KFC french fries

KFC Australia asked Ogilvy’s behavioral science team to increase customer interest in one of their annual product deals: one dollar french fries. Thanks to the nature of the product deal, Ogilvy couldn’t change anything about the fries’ retail price – meaning they needed to focus on the product’s perceived value.

One of the strategies Ogilvy used to affect how customers valued the fries was to trigger the anchoring heuristic. To do this, they emphasized a campaign disclaimer that was previously relegated to the small print: “maximum four per customer.”

Ogilvy found that adding an anchor to promotions changed consumer behavior, leading to a large number of people buying four orders of fries instead of one or two.

Source: Ogilvy Asia

Summary

What is a heuristic?

A heuristic is a method of decision-making or problem-solving, in which the problem is simplified so that a quick, efficient solution can be reached.

Why do heuristics happen?

Because we don’t have an unlimited amount of time in which to make decisions, our brains are disposed to look for shortcuts.

It’s not usually practical, or possible, to consider all the variables in a decision, so heuristics offer general rules to follow, which work in enough situations, enough of the time, to be helpful.

What impact do heuristics have?

When used appropriately, heuristics can save us time, allow us to act without spending lots of mental energy, and help us avoid a long accounting of the pros and cons.

When misapplied, however, heuristics can oversimplify situations, leading to biased thinking that strays from rationality. At their worst, heuristics can cause stereotyping and prejudicial beliefs – as well as systematic inefficiencies in businesses.

How can I avoid heuristics?

Our brains are optimized to use heuristics, which means that it’s not always possible to avoid them.

But practicing effortful or “slow” thinking can help us to consider the rationality of our actions, and whether we’re thinking under the influence of biases such as loss aversion or a preference for the status quo.