Anchoring Bias – Everything You Need to Know

Anchoring bias is one of the most powerful cognitive biases out there. Learn, how it works, how it affects you, and how to use it in business.

Article content:

Definition of the anchoring bias

Anchoring bias is a human tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information. This then serves as a reference point, or an anchor, if you will, which impacts all the following choices.

It can be a number that anchors our perception of price, or even our own previous decisions that guide our next choices. What is more, research shows that the anchor can be random, unrelated to our decision at hand.

How does the anchoring bias work?

Imagine these two scenarios.

In scenario 1, you walk into a Nike store with the intention of buying a new pair of shoes. You love the look of the very first pair you see is, with a price tag of $200. You walk to the other rack and find almost exactly the same-looking pair of shoes for just $150. It’s a no-brainer and you instantly buy the second pair.

In scenario 2, you’re casually surfing the web and you find a pair of shoes you like for $100. You’re pretty sure the Nike store is nearby, so you decide to go there to try on the shoes in person and then buy them.

The first information you get significantly affects your decisions.

But when you walk into the store, you find out it’s sold out. The salesman shows you a similar-looking pair for $150. He convinces you the pair is brand-new and made with the latest footwear technology, unlike the online model. Well, yeah, you think, but it’s not $50.The $75 model suddenly doesn’t look that great.

See? Even if the price was the same – $150, the first information you get significantly affects your decisions.

The truth is you can spot the anchoring bias at least a couple of times every day, whether it’s a discount that anchors you at a higher price and then satisfies you with a lower one, or your parents constantly grumbling about how everything used to be cheaper back in their days. You hope they get over it someday, but they won’t. The anchoring bias is that strong.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Why does it work?

It’s pretty straightforward – we cant make decisions in a vacuum. We don’t know if the price is too high or not or if the decision is right or wrong without any context. To estimate a price or a choice, we need to have a reference point. Then, we adjust our estimate around that reference point.

This is basically the first explanation of anchoring bias that comes from the OG behavioral economists themselves – Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. It’s called the anchor-and-adjust hypothesis.

Whenever we try to make predictions, we start with some initial value and then try to adjust it. Anchoring bias takes place when the adjustments are too small, which, they usually are. Let’s explain it in the example – try to answer this question:

How many liters of jet fuel do you think you need to fill up a tank of a jumbo jet? Is it more or less than 1 000? How much exactly? Write down your answer. Now, tap the shoulder of the first person you can find and ask the person a slightly different question:

How many liters of diesel does it take to fill up a jumbo jet? Would you say it’s more or less than 100 000? How much exactly?

We bet the numbers are not even close. You adjusted your estimate around the first piece of information you got. Your friend (assuming it wasn’t a random stranger) got to adjust her/his estimate around a different reference point. Hence, your answers differed.

See how easy it is to skew your judgment via article? Imagine what businesses could do when they try really hard.

Another explanation is called the selective accessibility hypothesis. To put it simply, when we are exposed to first information, being it a number, price, or any other concept, the areas of the brain related to that information remain active to some extent. This means the information remains easily accessible, influencing our behavior without us realizing it.

Anchoring bias experiments

The power of anchoring bias was proven multiple times through dozens of studies. Let’s get through some of them.

Same equations with different starting points

In the original study of Tversky and Kahneman, the scholars asked high school students to answer a mathematical equation within five seconds. The problem went like this:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1

Of course, not everyone got to solve the same equation. Another half was given the same sequence, but in reverse:

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8

The results? The average estimate of the first group was 2,250. The second group? 512! The starting numbers that people actually managed to multiply before giving a final estimate gave them a higher number, which then became the anchor.

Numbers from roulette affected participants’ estimates

In the same paper, Tversky and Kahneman made participants watch a roulette. A little the people knew that the roulette was pre-set to stop on either 10 or 65. With no malicious intentions except, of course, but strictly scientific purposes!

Participants whose wheel stopped on 10 guessed 25% on average, while participants whose wheel stopped at 65 guessed 45% on average.

Then, they asked the participants to guess the percentage of the United Nations that were African nations. Participants whose wheel stopped on 10 guessed 25% on average, while participants whose wheel stopped at 65 guessed 45% on average.

The arbitrary number led to higher expenses

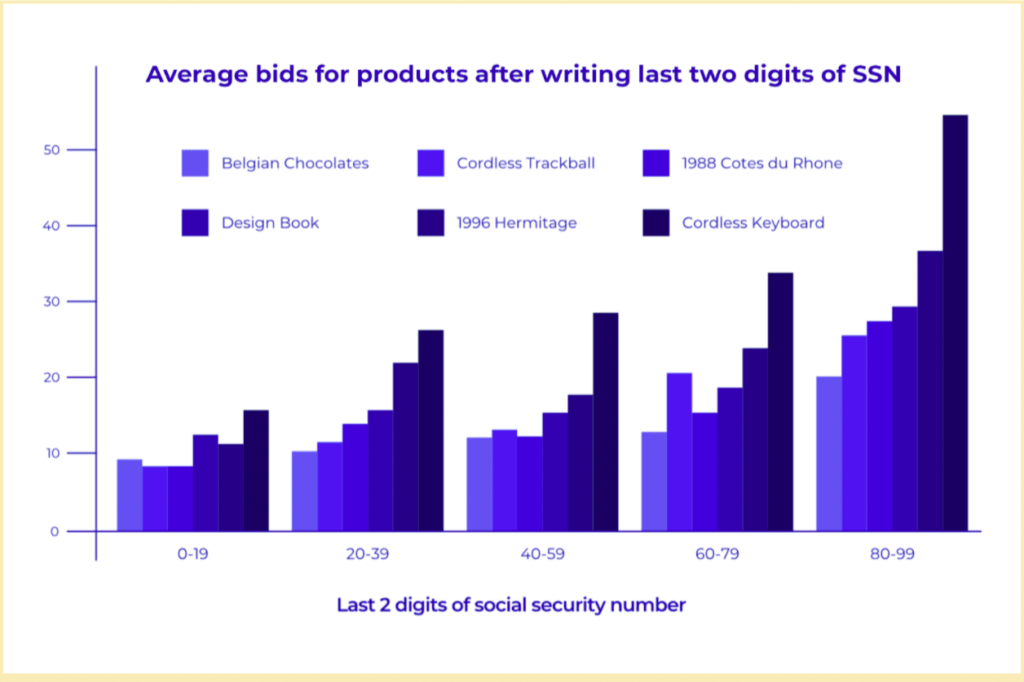

Researchers Ariely, Loewenstein, and Prelec asked MIT students to write down the last two digits of their social security number. Then they were presented with various products: a keyboard, exclusive chocolate, a bottle of wine, etc.

After that, they were asked to come back to the two digits and evaluate whether they’d be willing to pay more or less for these products. For instance, let’s say the last two digits of your social security number were 7 and 2, so you would be evaluating each product in terms of $72. Then, the students were asked to write the maximum amount of money they’d be willing to pay for each product.

You probably have a good guess how it turned out. Those with a social security number ending above 50 paid on average about twice as much for the products compared to those below 50.

Source: InsideBE

Rolling a dice affected judges’ sentencing

German judges with more than 15 years of experience were asked hypothetically to sentence a woman who had been caught shoplifting. But first, they were divided into two groups and asked to roll a loaded dice so every roll resulted in either a 3 or a 9. Both groups were then asked whether they would sentence the woman to a term in prison greater or lesser in months than the number on the dice.

Yes, it turned out the anchoring bias can skew the judgment of even experienced professionals. When later asked to come up with a prison sentence, those anchored to a 9 sentenced her to 8 months on average; while those anchored to a 3 suggested a 5-month incarceration.

History of the anchoring bias

It all started back in 1958 in the field of psychophysics. And yes, it’s an actual scientific discipline, not some sort of a superpower. In their article, researchers Sherif, Taub, and Hovland were testing how accurate were people in estimating objects’ weights.

At this point, it’s probably no surprise, but they found that objects with “extreme” weights influenced following estimations. They called those extreme objects anchors.

However, anchoring was not conceptualized as a bias until the 1974 famous article of Tversky and Kahneman called Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. The article contained the multiplying experiment and the roulette experiment mentioned above. No wonder the paper is nowadays considered to be groundbreaking.

How to avoid being anchored

Anchoring bias, like all the other biases, is subconscious. Changing something like that can be very challenging and getting rid of it completely might as well be impossible. However, there are techniques that can turn the subconscious into the conscious, which should help to realize it and fight it.

Red teaming

The first one can help you to make an unbiased decision as a team. Have you ever heard of red teaming? The idea is simple – simply pick a person, or even more people from the team whose main role will be to challenge the ideas and suggest alternatives.

Having an active team member who is constantly opposing the ideas of the majority will show weak points and may reduce the effect of anchor bias.

Having an active team member who is constantly opposing the ideas of the majority will show weak points and may reduce the effect of anchor bias. Plus, other team members will be less hesitant to come up with their own ideas and to disagree with the original proposal.

Consider the opposite

The second technique is similar but works on an individual level. Try to encourage even individuals to come up with at least one or two arguments against their own idea (generating reasons why an anchor is inappropriate). This is called “Consider the opposite technique”.

This means if I ask you whether the percentage of the United Nations that are African nations is higher or lower than 10% and what do you think it is, challenge your estimate. Isn’t it more? Africa is pretty big and contains a lot of nations, couldn’t it be higher?

The rationale is basically the same – to reveal weaknesses of one’s own decision, by coming up with arguments, why the anchor could be unsuitable.

Remember the selective accessibility model mentioned above? It says we get anchored because the anchor-consistent information is more accessible to us. Coming up with counterarguments weakens it and highlights the anchor-inconsistent information instead, moving us away from being biased.

Don’t come unprepared

In either case, the idea is to make the counterexample to the existing anchor way more accessible. Therefore, the tip you get from InsideBE is to be prepared. Whether there’s a team meeting or sales call with the vendor, think about what are you going to discuss and make your own estimates first.

Make the counterexample to the existing anchor way more accessible.

If you have no idea about the topic or price you are about to discuss, do your research. Businesses are very good at anchoring you on higher prices so you can spend more. But once you know the prices on the market well, you can again create your own anchor even before someone else try to do so.

Case studies

Anchoring increased sales of KFCs french fries by 56%

KFC asked Ogilvy’s team of behavioral experts to increase the perceived value around one of their products: $1.00 french fries. In other words, KFC wanted to sell more of $1.00 french fries, but without any changes in the product or pricing. That meant Ogilvy could only change how people saw it.

One of the things they tried was anchoring. Since the campaign disclaimer was “maximum four per customer”, the idea of anchoring came as one of the first. But – instead of using the number 4 just as a disclaimer at the bottom of the ads, Ogilvy turned it into the main headline:

Source: Ogilvy Asia

This not only anchored the customers but also changed the conversation from people talking about one dollar into how many can they actually buy: “If I go through the drive-thru twice, can I get six?”

A radio and visual campaign that was then rolled out ended in a 56% increase in total french fry sales compared to the previous year. And guess what was the main source of this uplift? The number of 4 french fry transactions, as it increased by 84%.

The most expensive hot dog in the world

Serendipity 3 is a restaurant in New York City that used anchoring in a bit extreme way. But it works! They simply created a very, very expensive hot dog. Actually, the $ 69 hot dog made it to the Guinness Book of World Records.

The fact that it created a buzz in the press goes without mentioning. But it may not come as a surprise that it wasn’t selling that well. That wasn’t the point anyway.

Source: Luxuo

Once it draws your attention and comes to the restaurant to see it, $17.95 for a cheeseburger suddenly seems like a much more reasonable price, doesn’t it? And that’s exactly how the anchors work. After introducing the hot dog, the sales of their cheeseburgers soared.

Nespresso changed the anchor to sell you €45 bags of coffee

This one is a bit different. Nespresso went far beyond changing the price and adjusted the whole context.

Imagine you’re buying a 474g (17oz) bag of coffee. What’s the highest price you would be willing to spend on it? €10? €20? €45?

Although €45 for a bag of coffee sounds ridiculous, if you did your calculations, you would have discovered that 50 cents for a pod of Nespresso and €45 for a bag of coffee is the same price per gram.

We buy coffee quite often so we know very well what are the prices per bag or per cup. This is already our anchor. Whenever we see a €45 bag of coffee, we compare it to the price we are used to so it seems far too expensive.

The brilliant idea Nespresso came up with was to sell their coffee in pods, which provide a cup’s worth of coffee. This changed the anchor – once we think of a cup of coffee, the natural comparison is not to compare it to a bag of coffee but to the cost of a cup at Starbucks. Suddenly 50 cents for a Nespresso pod looks like a pretty darn good value compared to €3,50 for an Americano at Starbucks.

Needless to say, Nespresso pods sell like hotcakes.

How to use anchoring bias in business?

Choose carefully what’s on the top of your product list

Keep in mind, that the first price your customers see becomes the anchor. Do you have a catalog? Menu? More package options or subscription plans? Be very careful about which choice your customers see as the first one.

Presenting the cheapest options first might seem reasonable at first, but it can backfire. As other options will seem a bit too expensive, there’s a pretty big chance the customer will choose the option on the cheaper end.

On the other hand, by placing pricier options at the top, surrounding options will look way more attractive. This was actually one of the strategies which helped a restaurant network to increase customers’ average spend by 13 pence.

For example, you might sell just a couple of bottles of Bordeaux Château Pontet-Canet per year, but having it on the top of your wine card can make the rest of the wines look like great deals. Your customer might not need the higher, most premium subscription, but listing it first will anchor them and make it more likely they will buy some of the less expensive options.

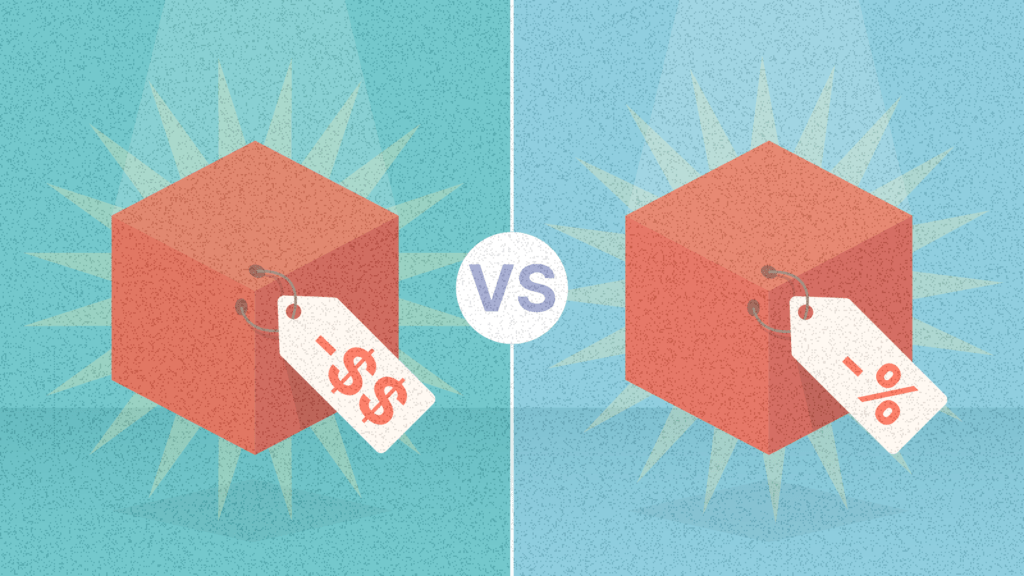

Change the anchor that customers compare your product with

This one is not easy, but if Nespresso could do it, so can you. Think of what is the natural comparison customers make when thinking of your product. What category is it in?

Perhaps you don’t need to change the whole product, but a change of environment would do.

In his online masterclass, Rory Sutherland speaks about the yogurt company Danone, which was very proud of their idea to put their yogurt drink in the milk aisle. It had the highest traffic in the supermarket – the more people will see it, the more people will buy it, right?

The problem is, the milk was way cheaper than their yogurt, so it anchored customers on a lower price, making the yogurt seem excessively expensive.

Luckily, someone cleverly recommended changing the anchor in another way – by putting the product in the premium yogurt section instead. Among other overpriced yogurts, it suddenly didn’t look like expensive milk, but rather a well-priced yogurt.

Negotiations

Anchoring might come in handy when negotiating a price, or salary. So, if you’re a business owner, working in sales, or just a job candidate about to discuss a paycheck, here’s a tip for you.

Imagine that you’re at a job interview and your target salary is $60,000, based both on your experience and industry standards. Do you really want to be given a number? What happens if you’re offered a salary of $40,000?

Gotcha, you’re anchored.

So you might stammer out a counteroffer of $50,000, worried still you might seem like an ingrate, when in fact, this is far less than you think you’re worth. Just because you were presented with the other party’s offer first, the possibilities for an agreement have narrowed in your mind.

Just because you were presented with the other party’s offer first, the possibilities for an agreement have narrowed in your mind.

The same goes for sales. The studies show basically the same thing, the first offer sets the anchor for the counteroffer. So far, multiple studies have shown that the party that comes with the first offer is in the advantage. The following counteroffers will be most likely anchored, and much closer to the original proposal.

So the ultimate tip here is – to try to make the first bid. It can save you a penny or two.

Summary

What is the anchoring bias?

An anchoring bias is our tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information. That then serves as a reference point and influences our following decisions.

We need that reference point to know if the price is too high or not or if the decision is right or wrong. Then, we adjust our estimate around that reference point.

How to avoid the anchoring bias?

Although not entirely possible, there are ways to mitigate its effects. The point is always to make the counterexample to the existing anchor more accessible.

When making team decisions, you can entrust a few people with a role to actively oppose the opinion of the majority. It will reveal the weaknesses of the argument.

At the individual level, it appears to be effective to encourage individuals to come up with arguments against their own idea (generating reasons why an anchor is inappropriate).

What also can help when deciding about the price is doing market research first, to set an appropriate anchor of your own.

How to use the anchoring bias in business?

You can use anchoring in three ways:

- Put pricier options at the top of your product list, so the other options won’t seem that expensive in comparison.

- Change the anchor that customers compare your product with. You can do that by simply changing the environment your product is in or changing the product itself.

- When negotiating, place the first bid. Counteroffers will then be much closer to what you wish for.