Loss Aversion – Everything You Need to Know

Loss aversion is a cornerstone principle of behavioral economics, affecting so much of how we think and what decisions we make. Read on to learn how it works, how to avoid it, and how to use it in your business.

Article content:

Loss aversion defined

As humans, when we gain or lose something, we feel it. Whether it’s a warm, proud feeling from finding a $50 note in our pockets, or a frustrated, annoyed feeling from losing a $50 bet with a friend. But did you know that we feel the pain from losses about twice as much as we feel the joy of equivalent gains?

Loss Aversion

We are roughly 2.5 times more sensitive to losses than we are to gains of similar size. A message framed as a potential loss might therefore be more persuasive.

Think about it. The emotion you feel when you lose a $50 bet is a lot stronger than the joy of finding $50.

Loss aversion is the human tendency to prefer avoiding losses over receiving an equivalent gain.

How does it work?

Our brains are hardwired to avoid losses as much as possible. This, in turn, affects how we make decisions relating to our resources (which span from money and items we own to intangible things like time and effort… But for now, we’ll focus on just money and items).

This bias can be useful, as it prevents us from making decisions that would otherwise leave us worse off in the end; such as spending too much when shopping, eating out when there’s food at home that’s about to spoil, or making risky gambles.

But loss aversion can also lead to irrational decision-making. For example, consider extended warranties on electrical goods. They exist on the premise of loss aversion: consumers are afraid that their newly-purchased item will break, so much so that they’re willing to pay for simply the certainty that if anything does happen, they can avoid a loss.

But these days, the majority of extended warranties on electrical goods are a terrible value for your money, with consumer rights policies, credit cards, and manufacturers already covering customer purchases. Not to mention the fact that the technology of these goods advances so quickly that most of the time, consumers are better off buying a new version than shelling out cash to repair their old devices.

Since people are so determined to avoid losses, they spend more money than is necessary just to protect themselves from the uncomfortable feeling of loss.

However, since people are so determined to avoid losses, they spend more money than is necessary just to protect themselves from the uncomfortable feeling of loss. Loss aversion also secretly commands so much of our decision-making, even outside of how people spend money.

This bias spills over into many aspects of our lives, from romantic relationships (like that one friend who won’t break up with her crappy boyfriend for fear of missing him) and our health decisions (vaccine hesitancy can stem from people’s fear of unlikely, yet severe side effects) to how we spend our time (like not buying tickets to see a new band because “what if they actually suck?”). It rules our lives without us ever noticing it.

Why does it happen?

There are different theories as to why we, as humans, are inherently loss averse, the most prevalent of which are evolutionary and biological in nature.

Evolutionary psychologists argue that there’s an adaptive benefit to being loss averse; after all, you’re more likely to survive if you end up with lesser gains than you are if you lose until you’re left with nothing at all.

Neuroscientists point to brain scan evidence showing that specific parts of our brains are activated when we are faced with a loss, including those that process fear and disgust.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Loss aversion experiments

Gambling

In Kahneman and Tversky’s seminal paper, they asked people whether they would take certain gambles, to see how they would choose.

At one point, they told people to imagine they had been given 1,000 ILS (the Israeli currency) and that they now had to choose to either:

- Take a gamble where they have a 50% chance to win 1,000 ILS; or

- Definitively win 500 ILS

Here, 84% of people chose the certain win of 500 ILS.

However, when people were told to imagine they had been given 2,000 ILS and asked to choose between:

- Take a gamble with a 50% chance to lose 1,000 ILS; or

- Definitely lose 500 ILS

Here, 69% of people chose to take a gamble.

Why is this odd? Well, both scenarios have the same expected outcomes from the starting point; the only difference is the first one is positive (you gain) and the second is negative (you lose).

This demonstrates loss aversion by showing that people are willing to take on risk to avoid a loss, even when they’re not willing to do the same for a gain.

People are willing to take on risk to avoid a loss, even when they’re not willing to do the same for a gain.

Asian Disease Problem

In Kahneman’s book, Thinking Fast and Slow, he describes the “Asian disease problem,” which is something along these lines:

“Imagine that the United States is preparing for the Outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimates of the consequences of the programs are as follows:

- If program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

- If program B is adopted, there’s a one-third probability that 600 people will be saved and a two-thirds probability that no one will be saved.

Unsurprisingly, the majority of respondents chose program A.

But where this gets interesting is when people were given a similar problem. The context of the US preparing for an unusual disease is the same, but the programs are different.

- If program A’ is adopted, 400 people will die.

- If program B’ is adopted, there is a one-third probability that nobody will die and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die.

When presented with this problem, a large majority of people chose program B.

This is interesting, because, if you calculate the outcome, program A and A’ have the same result, as do program B and B’.

When faced with a potential loss, Kahneman found that people are willing to take on more risk in order to avoid a loss.

So why do people choose different answers for each problem, despite the choices being the same?

Once again, this is because the two problems are framed differently. Problem 1 is presented in a gain frame (people are saved), whereas problem 2 is presented in a loss frame (people die). When faced with a potential loss, Kahneman found that people are willing to take on more risk in order to avoid a loss.

History

Prospect Theory

Don’t take it lightly when someone says loss aversion is a cornerstone principle of behavioral economics. Because it really is.

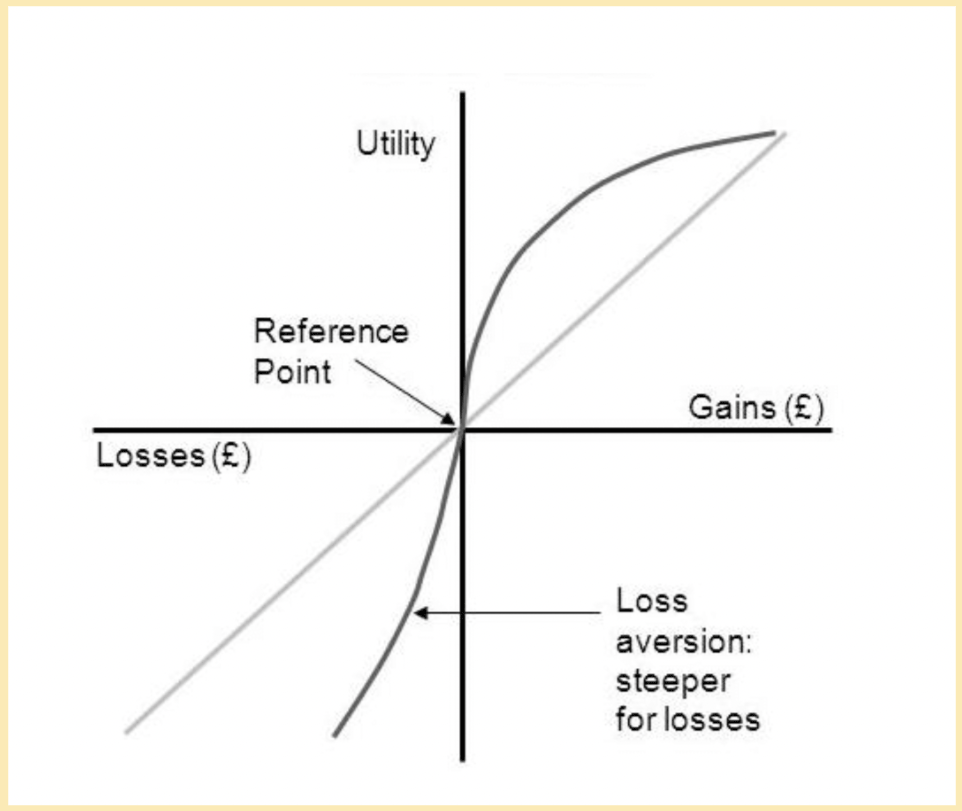

It all started with what is now known as the seminal paper of behavioral economics: Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.

Thanks to this paper, which was published in 1979, the authors Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky earned the title of founders of the field. The paper was written as a critique of traditional economics, and started the rapid growth of what we know now as behavioral economics.

Specifically, the paper criticized the idea that people are rational decision makers: perfectly calculating the total value of any choice and choosing the option that maximizes it.

Through this, Kahneman and Tversky described 3 principles of decision making under risk: reference points, diminishing sensitivity, and loss aversion.

These are perfectly captured by perhaps the most famous graph in behavioral science, depicting the psychological value of gains and losses.

Source: Researchgate

See how the value curve is steeper on the loss (left) side than on the gain side? That is loss aversion.

Risk Attitudes

Kahneman and Tversky continued to develop prospect theory and their ideas of loss aversion. A key feature of this development was understanding how people make decisions that involve risk.

Previously, it was thought that people avoid risk in all situations, however Kahneman and Tversky argued for and found evidence of consistent risk-seeking decisions.

They discovered that people tend to be more risk-seeking when they’re faced with a loss and more risk-averse when they’re faced with a gain.

The Endowment Effect

The Endowment Effect

When people own something they value it beyond its objective value. Frame your message in ways that make customers feel like they already own your product, discount or benefit.

Inspired by Kahneman and Tversky’s work, economist Richard Thaler identified a bias related to loss aversion in 1980: the endowment effect.

The endowment effect describes people’s tendency to put more value on an object they own than on one that they don’t.

Thaler wanted to explain why people were so desperate to avoid losses, and argued that it was because they attributed an irrationally high value to the things they owned, so it hurt more to lose them.

Sunk Cost Fallacy

But Thaler didn’t stop there. In that same paper, he also brought in the idea that people tend to be reluctant to abandon a course of action when they’ve already invested (time, money, effort) in it: now referred to as the sunk-cost fallacy.

An example of this is ‘getting your money’s worth’ by going to an event that you’ve already bought tickets for, despite you not really wanting to go, because hey, you’ve already spent the money on it so you may as well, right?

The sunk-cost fallacy is closely related to loss aversion, with people’s fear of loss making them stick to bad investments. Because we don’t want to feel the uncomfortable feeling of loss, we refuse to accept that we made a wrong decision, leading us to make more losses by doing so!

Current Thinking and Criticisms

As a cornerstone principle of behavioral economics, there has certainly been a lot of studies looking into loss aversion.

A theme that has emerged is that loss aversion is a lot more nuanced than previously thought. Evidence seems to consistently show that loss aversion does not occur in all situations, and not in the same way in different situations.

The debate rages on, with current thinking converging to the point that loss aversion shouldn’t be accepted as a pure principle that is true in every scenario, but rather as contingent on other factors, such as magnitude, knowledge, and age.

How to avoid it

Annoyingly, just being aware of loss aversion doesn’t ‘cure’ the bias: we’ll still always fear losses and losses will always suck.

However, there are ways to avoid getting sucked into the spiral of loss aversion.

Change the framing

When you find yourself in a loss-facing scenario, reframe it. Consider what you’re gaining, and put that at the forefront of your mind.

For example, a familiar scenario: FOMO. Your friends have gone out and you’re regretting your choice of staying in that night. You consider all the dancing, fun stories, and bonding between your friends that you’re missing out on. That sucks!

But what if you consider, instead, what you’re gaining? You’re gaining a period of rest, time to truly recover from the busy week you’ve had, and a chance to finally savor that new red wine you bought last week that you’ve been dying to try. Ahh, much better.

Remember that not everything is scarce

Remind yourself that even if you do take a loss, there will almost always be a chance to replace it. There will always be another sale, good food, clothes that you like, and a chance to spend time with your friends.

This will stop you from scrambling to prevent the loss in front of you and give you the chance to evaluate your decision more holistically.

Change your reference point

Similarly, reconsider your perspective.

Imagine you have an older relative that you’re not too close to, but is part of the family that you spend Christmas (or Hanukkah, or Chinese New Year) with every year. Every year for the past 10 years, since they don’t know you too well, this relative gives you an envelope with $50 in cash.

Then one year, you open the envelope to find only $25. You’re confused and disappointed. Where’s the other half?

Next time you’re facing a loss, reconsider where you started, and how if it were different, you would feel very different about the same situation.

But, consider this: what if you had never before received a gift from this relative. Yet, this year they pass you an envelope with $25. You’re delighted! An extra $25 to spend on yourself, how wonderful!

Despite the same occurrence (receiving a $25 gift), your reactions are completely different.

So next time you’re facing a loss, reconsider where you started, and how if it were different, you would feel very different about the same situation.

Learn to move on

This is a hard one, but can have a very positive spillover into all aspects of your life. Try not to hold onto losses and focus on moving forward. Failing is a part of life, and by making mistakes, you learn. Maybe that loss isn’t so bad after all.

Examples and case studies of loss aversion

Home Energy Use

How can you get people to reduce their energy use? By using loss aversion, of course!

In one study, psychologists tried to encourage homeowners to reduce their total energy use. After offering a free energy audit, half of the homeowners were told:

- “If you will insulate your home fully, you’ll be able to save 50 cents a day, every day.”

The other half were told:

- “If you fail to insulate your home fully, you’ll lose 50 cents a day.”

Simply by changing the phrasing of the advice: from a gain frame to a loss frame, 150% more people chose to insulate their home.

Taxify (now known as Bolt)

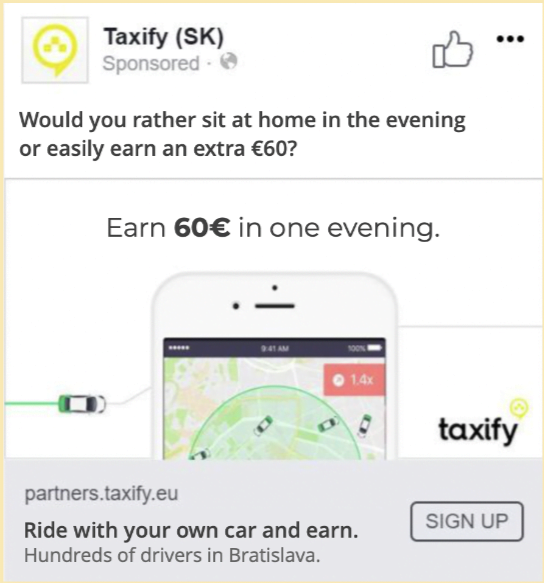

Can loss aversion also be used to inspire people to work? Of course it can.

Taxify, a ride-sharing app like Uber, wanted to get more people to start working as drivers. This is hard, with many potential drivers working other jobs as well, meaning that motivating them to work would require pulling them away from the comfy alternative: resting at home.

This challenge could only be overcome with one thing: loss aversion.

Instead of telling people “Earn decent money driving your own car. No minimum hours, freedom to drive whenever you want,” they were now asked “Would you rather sit at home in the evening or easily earn an extra €60?”

This framed the lazy evening at home as a loss, especially a quantified one at that, inspiring people to sign up to work. This was incredibly effective, increasing conversion rates by 54%.

Source: Facebook

How to use it in business?

Free trials

A great method to use loss aversion in business is by offering a free trial of your product or service.

Consumers love this, as they are drawn in by the power of “Free!”. Only gains to be had here!

But, what happens at the end of the trial? Once a consumer has the product, or has gotten used to having the service, it becomes a lot harder for them to give it up because now they have to face a loss.

An example of this is Spotify. Their basic plan is free – you can listen to all of the music on the platform, as long as you’re willing to sit through an ad every few songs.

Source: Spotify

After a while, you start getting adverts for Spotify Premium, featuring an offer of a month of the same music you have now, just ad-free. You’d be crazy to pass it up.

You think to yourself: “I’ll just use the month and then go back to ads, after all, it’s a waste if I don’t.”

But no one ever does. After you get used to that sweet-sweet experience of uninterrupted music, it is a tremendous difficulty to let go of that privilege.

The key to using this effectively is in the length of the trial. It should be long enough that the customer gets very comfortable and used to using the product or service regularly, but still short enough that the trial is not unprofitable for the business.

Creating Urgency Carefully

A very common sales method is to create a sense of urgency for potential customers. This use of urgency isn’t groundbreaking, but by understanding the principle behind this tactic, you can maximize its impact.

What most marketers do is create limited-time offers, place countdown timers all over their websites and, a personal favorite, mention that others are looking to buy.

Source: Dafni Hair

But what they’re failing to highlight is the driver of this urgency: the fear of missing out.

Instead of just saying the offer is limited, highlight the loss that is created if they don’t use the offer. Tell them how much more money they will spend if they don’t take advantage of the offer.

Or, when mentioning that others are looking to buy the same thing, highlight very clearly that the customer stands to miss out on the product they want.

Reframing

Finally, the most important and applicable way you can use loss aversion in business is through the power of reframing.

Simply reframe critical points as losses and highlight that by not acting and by not choosing, the person is losing.

Reframing refers to changing the way something is presented to an audience. This ‘something’ can be anything from a narrative, to a choice, to a statistic.

The application of this is so overarching that you should keep the principle of loss aversion in your back pocket when you’re trying to persuade. It can be used everywhere: in advertising, sales, negotiations, presentations, and more.

Simply reframe critical points as losses and highlight that by not acting and by not choosing, the person is losing.

For example, consider a proposal for a potential client.

You could say: “You could get hundreds of new clients by learning how to use some of the most powerful behavioral principles.”

Or equally, you could reframe that to: “Right now you might be losing hundreds of clients because you don’t take into consideration what’s going on in their minds.”

Same concept, different framing.

The first message tells the client that they’re doing well, but could be doing better. Not so bad. But the second message tells them “Hey! Wake up – you’re losing now – you need to do something about this!”, instantly motivating them to act.

However, a word of caution for those using loss aversion in their business: although it can be a powerful motivation tool for encouraging customers to take action, it can be detrimental when trying to induce a long-term behavioral change.

Loss aversion is a good trick to have up your sleeve, but overusing it can make experience with your company unpleasant and reduces the chance to build credibility with your customers.

Summary

What is loss aversion?

Loss aversion is the tendency for people to act more to avoid losses than to acquire equivalent gains.

How/Why does it work?

It works because losses are perceived as psychologically more severe than an equivalent gain, making us more motivated to avoid losses as much as possible.

How to avoid it?

You can avoid loss aversion affecting your decisions by reconsidering the framing, reminding yourself that there will be more opportunities in the future, adjusting your reference point, and learning to move on.

How can I use it in business?

To use it in business, you can offer free trial periods, underline what’s at stake when creating urgency, and reframe your propositions to highlight loss.

Additional resources:

- Loss Aversion

- Loss Aversion in Marketing

- 15 Examples of Loss Aversion

- Behavioral Finance, Risk Profiling and Prospect Theory

- The Psychology behind Consumer Regrets, or Loss Aversion

- Loss Aversion and Customization: Using 3D for Better Sales

- Applying Loss Aversion Bias to Modify Consumer and Employee Behaviour

- Thinking About the Cognitive Bias of Loss Aversion in Underwriting

- The Psychology of Upgrade Emails: Make Something to Lose

- How to Implement Digital Psychology Into Your Marketing: Anchoring, Commitment, and Loss Aversion

- How to use loss aversion to inspire action in B2B marketing