How-To Design Against Pitfalls of Traditional Market Research

We often encounter the “say-do” gap with customers; simply put, there exists a gap between what people say and what people actually do. Leaning heavily on self-reported responses can be dangerous, as they are likely to be rationalizations often not reflective of customers’ decisions.

In this article, you will learn:

- When traditional market research works and when it’s likely to fall short;

- What pitfalls marketers and researchers should be aware of; and

- How to design and conduct research to avoid such pitfalls.

Traditional market research is omnipresent and has been around for ages, and it encompasses a variety of qualitative and quantitative tools. It is often used to test concepts, features, product ideas, advertisements, and campaigns with customers.

When done right, it can be leveraged for well-scoped, focused testing with small sample groups or to scale findings from qualitative research and validate them en masse.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

The shortcomings in market research, such as defining a research objective poorly, self-selecting samples, applying a blanket set of research tools for all problems and the biases in conducting them, drawing inferences too literally, and reporting them with overwhelming certainty, have all led companies into PR nightmares, product recalls, and even massive shutdowns.

While there is an established utility of conducting first-hand research, there are numerous cautionary tales of findings from surveys and focus group testing being applied to products or for marketing. Think Coke’s attempt to reinvent itself with New Coke, a ploy for healthier, clear soda with Crystal Pepsi, or McDonald’s misguided attempt at the sophisticated Adult Burger.

It also poses the danger of missed opportunities. As the famous quote associated with Ford goes: “If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they’d have said faster horsepower.”

When we go above and beyond traditional methods, we get a chance to peer into people’s underlying motivations, desires, needs, and fears, thereby bringing us closer to designing meaningful products, services, and experiences for them.

When we go above and beyond traditional methods, we get a chance to peer into people’s underlying motivations, desires, needs, and fears.

In the following section, we will look at the pitfalls, recommendations, and emerging approaches for each key aspect of the research journey: Objective Setting, Sample Selection, Parameters & Methods, Conducting Research & Analysis, and Inferences & Outputs.

Defining the research objective

Confirmation-driven research

Research that is done to tick a box after the strategy is already defined. This places consumer input as the last step instead of the first.

Ex. Will customers buy this product or not?

Discovery-driven research

Start with a scope/problem frame that allows for the exploration of core and peripheral needs of the consumer, immerse yourself in their context, and allow the strategy to emerge organically as opposed to force-fitting one, thereby enabling problem reframing within the given scope.

Ex. What drives customers to purchase products in this category? What is the environment of their purchase decisions for this product?

Hypothesis-driven research

Articulate a behavioral challenge and define a science-based hypothesis about consumer decisions that can be tested and explored. In a study conducted to design solutions to drive charitable donations in the UK, the starting point for intervention testing came not from what customers said, but from behavioral science-led hypotheses, revealing not just 1, but 3 solid interventions with over 10% increases in donations.

Setting the criteria for sample selection

Self selection bias

Be careful with paneled participants, although they provide convenience for recruitment, they’re also a self-selected category of people. They can easily become trained and desensitized to research, thus producing highly rehearsed responses that are unlikely reflective of their behavior.

Purely demographic-based segments

Boxing people into personas that are superficial, such as age-driven or location based. The world is far more connected today, further engineered by the pandemic.

Ex. Assuming that older groups are less tech-savvy or that younger groups are more likely to be socially-conscious in consumption.

Representative samples and behavioral segments

Including psychographics, attitudes, and behaviors into segmentation can provide a more holistic view of the customer, thus allowing for more representation in the samples. Data can be used to identify behavior-driven groups better in order to avoid researcher bias creeping in at this stage.

Ex. For a media client, instead of splitting their target group based on age/gender/location, the target group’s purchase and viewing behaviors were studied in depth, and 3 engagement-based behavioral segments were identified: Transactional Customer, Engaged Customer, and Invested Customer. The communication strategy and marketing outreach were mapped to each segment and were proven to be more effective.

Note: Behavioral segments can be identified from customer goals, purchase/engagement patterns, or even their attitudes towards the product.

Extreme users

The inclusion of “extreme users” or “future users” can be an interesting addition to the sample. They are people that are unlikely users – this could be an age group, a gender, a cultural background, or even users that are engaging with the product in a heightened/highly negative/unexpected way. They are not the core group at this moment in time for the product, but their perception and engagement with it can produce insightful findings for core users and for present and future directions of the product too.

Articulated research intent vs. real intent when screening

Be conscious of what research intent is being shared with participants, as this can sway their responses drastically. Within the bounds of ethics, try giving a broader, non-specific intent so that participants can’t game the research. Participants can over-index towards pleasing researchers or playing difficult consumers if they know exactly what the research goal is.

Participants can over-index towards pleasing researchers or playing difficult consumers if they know exactly what the research goal is.

Ex. If customers know what the desired response to a screener question is, they’re likely to select it even if it’s untrue. Provide equally acceptable responses without a clear winner.

Deciding what to test and how to test it

Opinions and rationalizations

Avoid lines of questioning and inquiries that seek opinions from consumers. Individuals aren’t often aware of the drivers of their behavior, so when asked what they think, they’re likely to share either a flippant or highly processed response.

Ex. “What do you think about this feature?”

Leading questions

Avoid close-ended, leading questions. Leading questions allow the respondent to know what the “right” or desirable answer is. Close-ended questions are conversation-enders, they break the flow of conversation and don’t allow the researcher to go any further on the why.

Ex. “You would use this, right?” “If we reduced the price, would you buy this?”

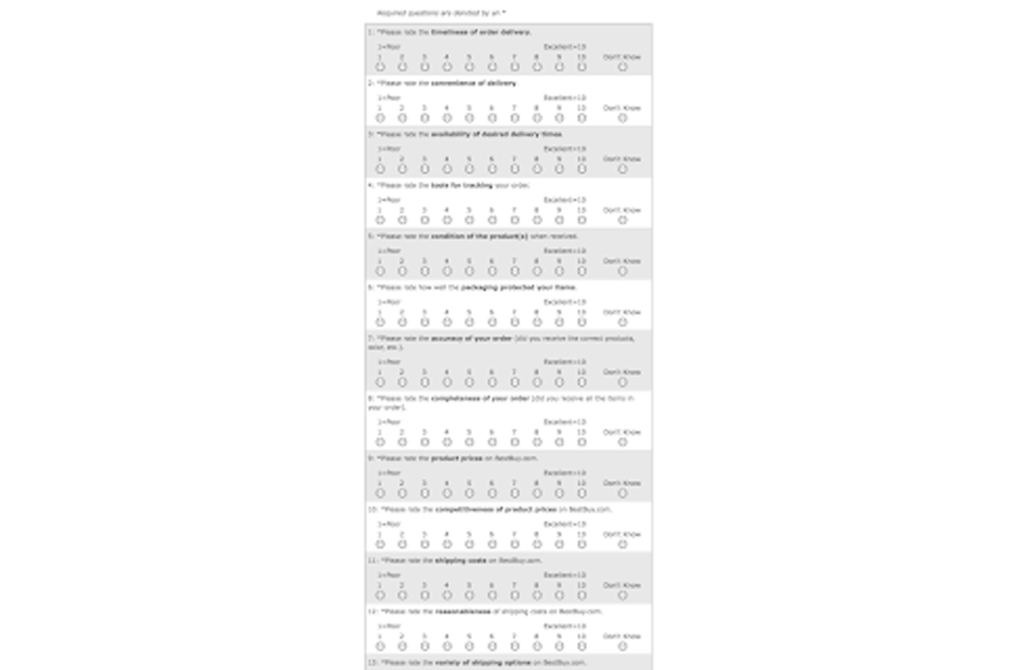

Different problems, same tool

There is no silver bullet in research. Each study demands a curated set of tools for optimal insights. It is worth brainstorming and coming up with unconventional, innovative ways to design the study depending on the objective, the cohort, and the constraints.

Ex. Trying to apply the same research techniques for remote and in-person research can be problematic. When remote participants are not in the same context as the researcher, they have a higher chance of disengaging and there’s an increased likelihood of more distractions and a reliance on technology. Not making necessary updates or changes and having an appropriate format for the tool can gravely impact the quality of the work.

Language barriers

When extending research to multiple cultural contexts and geographies, it is essential to look at how the questions translate, not just whether or not they convey the same meaning, but also looking at the essence and cultural relevance of the questions and language.

It is essential to look at how the questions translate, not just whether or not they convey the same meaning.

Ex. Using the word ‘ill’ for ‘disease’ is acceptable in some cultures, but in the US, it was found to be more associated with mental illness. A better word to use was ‘unwell’.

Behaviors, decisions, emotions

Seek to observe and identify consumer behavior, ideally in their actual decision-making context. These can be studied with direct observation studies, triggering storytelling from customers, or simulated games.

Ex. Studying purchase behaviors from a sample of over 6-12 months in addition to speaking with customers; simulated games to study decision-making; and walk/shop-alongs with customers.

Bringing AI and behavioral research together

Leveraging data to derive behavioral hypotheses and using observed behaviors to seek data patterns in tandem can be a good way to bolster and bring immense depth to your research.

Conducting the research:

Researcher bias

Even the best of researchers can fall prey to their own biases, especially when the stakes are high and there’s a desired outcome from the study. There’s evidence that the tone of the researcher and their disposition can highly influence participant responses. While we can never be bias-free, having a team present for research (observers/recordings/debriefs can help too) can help identify how one’s behavior influenced responses, and take that into consideration when drawing inferences.

Participant bias

Much like researchers bring bias to the table inadvertently, participants can too. These could come in the form of anchoring – where the first/most dominant voice in the room can influence the responses of others and social proof – where participants may seek belonging in a group they identify with and represent the opinions of the group above their own. The structure and flow of the study should proactively account for these and take them into consideration during analysis.

Reduced response fatigue, counter-biasing

Breaking monotony in research tools can help debias responses and also reduce fatigue/automaticity that might kick in while the participants are responding. Bringing some spontaneity, variation, vividness, personal relevance, or novel stimulus can help keep the respondent engaged.

Ex. leveraging audio, visuals, and engaging senses to keep the respondent present

Highly structured script or survey

Even the best researchers can only create options that they’re able to picture and customers may feel/do something other than the options that are presented. If not given an opportunity to share, they will be forced to respond within the boundaries of the researcher’s imagination. Giving respondents some room for relevant tangents or unstructured responses can be a great way to peek under the hood and see what their free flow dialogue reveals.

Ex. Sticking to a discussion guide, even when interesting nuggets are sprouting in conversation naturally

Putting customers in the decision-context

Try to bring the respondent into the “hot-state” – i.e. the decision-making mindset as much as possible. Storytelling triggers that place the respondent in a real decision-making situation can be used to create this.

Ex. “Could you tell me about a time you felt surprised / delighted / annoyed with this product?” “Could you tell me the last time you were afraid about your health?”

Story Cues: First time, last time, recently, 1 year from now…

Drawing inferences and sharing outputs

Lies honestly told

Behavioral research acknowledges that participants are often sharing what they believe to be true about their decisions because the real motivations and drivers are not available or known to them. Try to see the story behind what they’re reporting.

Ex. Diabetes patients often underestimate how often they skip their medicines as they develop personal hacks and rules, thus believing they’re more adherent to their medication regime than they actually are

Manage findings to satisfy results

Much like how a confirmation-driven research objective doesn’t serve products well, neither does stitching, ignoring, or selecting findings, quotes, and participants to showcase a predetermined result. As a matter of fact, these things can be highly detrimental to products as well. Allow the strategy to emerge organically through the stories that are heard during your research.

Ex. using a dramatic quote from the field, even if it was an isolated one; using quotes out of context to make a point

Room for clarification, review, and updating

Allow room for clarification between team members and ideally with respondents too. If there is a conflict in what team members took away from a study, it is worth it to go back to study the recordings or even reconnect with respondents if possible.

Ex. allowing participants to share feedback/open-ended comments with their responses in case they interpreted a question a certain way and would like to explain their response

Experiment design

Learning from quantitative experiments, especially those enabled by technology (Ex. A/B tests), can prove to be beneficial for traditional research as they allow for many rounds of validation. There can be quick updates to the testing material, inputs and outputs can be more structured, and research can be more evidence-based and scaled as needed.

Ex. learning from A/B tests for feature testing, longitudinal studies, marketing experiments, and growth marketing tests.

Key Takeaways:

- Look beyond the demographics. Look for behaviors for segmentation.

- Avoid opinions and post-rationalizations from customers and instead observe their behaviors, actions, and decisions.

- Avoid leading questions, close-ended inquiries, and highly structured discussion guides. Allow for meaningful tangents.