Representativeness Heuristic – Everything You Need to Know

Article content:

Definition of the Representativeness Heuristic

The representativeness heuristic is an automatic mental shortcut we use to make assumptions through stereotyping.

We rely on it when we need to make decisions about unfamiliar things or people. It helps us quickly assess whether something new fits into our existing model/prototype or not and then it helps us know how we should behave.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

How does it work?

Imagine you’re at a sports store minding your own business when a person approaches you asking where they can find a bike pump. As they inspect your perplexed face and black fleece jacket more closely, they notice you don’t actually work at the store. Their preconceived notion that anyone wearing a black fleece is an employee is an example of a representative heuristic.

In this case, the stranger compared a current situation or scenario (your appearance) to some preconceived notion or stereotype of what a typical store clerk wears (a black fleece jacket). It led them to make a quick snap judgment about you (that you are a store clerk) and a decision to ask you for advice.

Why does it happen?

Each day, we are asked to make thousands of decisions, so it’s no wonder our brains aim to do so while conserving as much energy as possible. Shortcuts save time but they can also lead us astray. Relying on them doesn’t mean we make the right decisions, just quick ones.

Source: YouTube

The representativeness heuristic stems from more than just our proclivity to make quick decisions with limited information. It is deeply rooted in our innate predilection for categorizing things. Categorization not only helps us to make sense of something new, but also to remember it.

Categorization not only helps us to make sense of something new, but also to remember it.

Imagine if every time you encountered something new, you had to learn from scratch what it was and how it worked. And then after all that strenuous mental work was done, you would have to store all the unique information about every separate entity in your brain! Whoa, that would be nearly impossible!

But since we have categories, we can readily draw on stereotypes to make judgments about new things. It means we know how to behave when interacting with something new almost immediately, as opposed to having to take time to understand each unfamiliar new thing we interact with.

Representativeness Heuristic vs. Bias

Although the terms representativeness heuristic and bias are sometimes used interchangeably there is a difference. A heuristic is an intuitive mental shortcut – a rule of thumb based on past experiences – which helps us make decisions quickly and efficiently, especially when there’s limited information and/or we need to make on-the-spot choices or judgments.

A heuristic is an intuitive mental shortcut which helps us make decisions quickly and efficiently, especially when there’s limited information and/or we need to make on-the-spot choices or judgments.

Bias is a heuristic’s rowdy cousin; it’s a systematic error that may lead to suboptimal decisions. In the case of representativeness bias, it means that when we draw conclusions based on preconceived notions or stereotypes, we may overlook more nuanced or crucial information.

Bias is a systematic error that may lead to suboptimal decisions.

For example, a doctor could tell a patient who has recently unintentionally gained weight that they need to work out more because the stereotype is that an overweight person must be a couch potato. However, unintentional weight gain may have other causes, such as thyroid disease, hormonal imbalance, or even heart disease. What that means is that the doctor might not prescribe further tests because they are under the spell of stereotyping, and instead send the patient off with advice to pump more iron.

The representativeness bias can also feed prejudice and systemic discrimination. It means we adopt generalized beliefs that members of a group will have certain characteristics, but overlook more nuanced information about the individual.

For example, police who are looking for a suspect in an armed robbery might focus disproportionately on young black males because their stereotypes lead them to assume that a black youngster is more likely to resort to gun violence than a person of a different race.

Representativeness Heuristic experiments

Let’s look at some famous studies that had scientists scratching their heads about how much educated people can err under the influence of representativeness.

Steve the (un)likely farmer

In a now classic Kahneman and Tversky experiment, the research pair asked unwitting participants to solve the following puzzle:

“Picture Steve who is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful but with very little interest in people or in the world of reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail. Is Steve more likely to be a librarian or a farmer?”

The inconvenient truth is that representativeness doesn’t have anything to do with probability, but we still put more value on it than we do on information that is actually relevant.

Do you intuitively feel like Steve must be a librarian because he’s more representative of your image of a librarian than he is of a quintessential farmer? You are not alone. Most of the participants felt the same way.

The inconvenient truth is that representativeness doesn’t have anything to do with probability, but we still put more value on it than we do on information that is actually relevant. Such as the fact that in statistical terms, it would always be incorrect to say that Steve, who lives in the U.S., is “more likely” to be a librarian because there are 7 times more male farmers than there are male librarians in the U.S.

But alas, these statistics simply do not come to mind and/or are overridden by the fact that our associative memory quickly creates an image of Steve, the shy librarian. It feels more innately true. And that’s where we err.

The “Linda problem”

The representativeness heuristic is so pervasive that some other biases and heuristics stem from it. One of them is the conjunction fallacy, which assumes that it’s more likely for multiple things to occur at the same time than it is for a single thing to happen on its own.

Statistically speaking, this is never true as it violates the most basic laws of probability theory. The conjunction fallacy was observed during an experiment which Kahneman refers to as his most controversial.

Subjects were asked to read the bio of a young woman named Linda:

“Linda is thirty-one years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.”

Yes, it left a lot to be desired as a Bumble profile, but swiping right on Linda was not the point of the experiment.

After reading this, people were asked to play a version of Identity which involved ranking several statements in order of how likely they were to be true. “Linda is an elementary school teacher”, “Linda is active in the feminist movement”, “Linda is a bank teller”, “Linda is an insurance salesperson” and finally “Linda is a bank teller who is active in the feminist movement.”

Even though the last statement is a special case of the third statement, more people deemed that Linda being a bank teller and a feminist was more likely than Linda just being a bank teller.

Yes, it should take no more than five seconds to realize that there are fewer female feminist bank tellers than there are female bank tellers (regardless of their worldviews). But remember we are all under the influence of a compelling description of Linda which is in line with our prototypical image of a feminist. Representativeness bias skews our perception of probability so that even though it is statically less likely that Linda would be both a feminist and a bank teller, it feels more likely.

History

The concept of sorting objects into categories can be traced back to Plato and his not-so-hopeless student, Aristotle, who tried to sort every object of human apprehension into one of 10 categories. Ambitious, right?

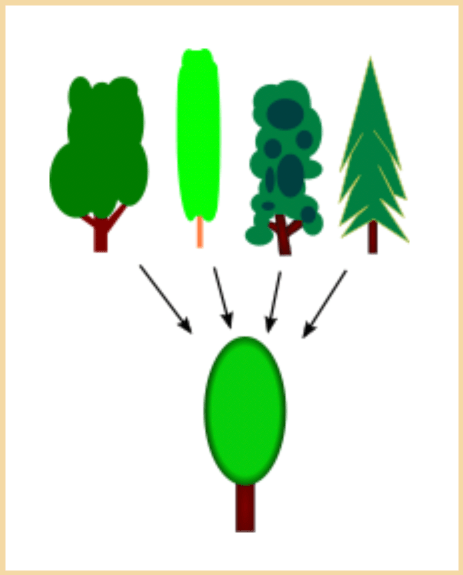

In the early 1970s, Prototype theory was coined by the psychologist Eleanor Rosch who took a more nuanced approach to categories. She recognized that members of a given category can often look quite different from one another. It also means that we regard some objects, animals, and people to be “better” category members than others.

Source: Wikipedia

For instance, penguins, while technically belonging to the category of birds, just don’t seem to fit into the group as neatly as an eagle. From there emerged the notion of a prototype: a certain category member that is viewed as more representative of its category than others.

The notion of a prototype: a certain category member that is viewed as more representative of its category than others.

And finally, the term representativeness heuristic was coined around the same time by Kahneman and Tversky who, as you have seen, have done a fair amount of research on the strategies we use to make judgments about probabilities which can lead to systematic errors in judgment.

How to avoid it

Categorization is so fundamental to our perception that it can’t (nor should) be erased; we simply can’t avoid the effects of the representativeness heuristic altogether. However, just knowing that such a shortcut exists is a good start.

Consider sample size

When our focus gets hijacked by representativeness, a useful type of information we often neglect is sample size.

Picture a jar filled with candy bars. You draw 5 bars from the jar, 4 of which are Mars, and one is a Milky Way. Your friend (and one lucky devil) Arthur is allowed to draw 20 bars from the same jar. He draws 12 Mars bars and 8 Milky ways. Between you and Arthur, who should feel more confident that the bars in the jar are ⅔ Mars and ⅓ Milky Way?

You might think (like most people) that you have better odds of being right because the proportion of Mars bars you drew is larger than the proportion drawn by Arthur. But the assumption, based on comparative ratios, is not correct.

Before you jump to any conclusion, consider the overall likelihood of a certain event based on the relative sample size.

Remember, Arthur was allowed to draw 20 bars, which is four times more than you were (goddammit!). So, apart from getting diabetes, he is in much better shape to judge the contents of the jar. And yet most of us are intuitively tempted to go for a 4:1 sample because it is more representative of the ratio we’re looking for than Arthur’s 12:8.

So, before you jump to any conclusion, consider the overall likelihood of a certain event based on the relative sample size.

Remember to think like a statistician

The effects of the representativeness heuristic can be erased by cues that encourage us to think like a statistician. The problem is that we don’t tend to do that naturally – not even the more educated among us, such as graduate students. With that being said, there is evidence to show that the conjunction fallacy can be reduced in children if they are informed about it in advance of dealing with a problem.

Slow down

When we’re worried or anxious, implicit biases that help us categorize information and make decisions quickly, take over. A way to counter that is to slow down and reflect on what you are about to do, so you can make more rational, less fear-driven decisions.

The online platform Nextdoor noticed its users were disproportionately tapping its one-click crime and safety function to report suspicious behavior of black men, so they changed the functionality to make users pause and reconsider.

Users were asked to go through a checklist answering questions such as: “What is it about the person’s behavior that makes them suspicious?” after which they had to describe the person in detail (simply saying they’re a black man would not do). Then the platform told them they might be engaging in racial profiling, which was prohibited.

All these interventions decreased racial profiling by 75%. So remember, when in doubt you can slow down too.

Nextdoor also played with the claim “if you see something, say something” which usually appears in public places such as subway stations and metro carts, and replaced it by “if you see something suspicious, say something specific.”

All these interventions decreased racial profiling by 75%. So remember, when in doubt you can slow down too.

Examples and case studies

Even though representativeness bias is prevalent there is a way to combat it, even in business.

The My Big issue

The Big Issue social change organization which helps disadvantaged people escape from poverty was struggling to help its vendors make more money.

Wearing big blue bibs with a giant The Big Issue sign, they were selling the magazine to drivers stopped at traffic lights. But as soon as drivers saw them, the representativeness heuristic took the front seat – the bibs further exacerbated preconceived notions and negative stereotypes about the vendors.

So, they redesigned the bibs by changing “The Big Issue” sign to “My big issue”. Beneath the sign, they added the vendor´s handwritten personal problem, making it more authentic. This change created an opportunity for drivers to empathize with the vendors.

With this, the buyers felt like they were really making a difference, moving the vendors closer to their goals, not that they were just being asked for money willy-nilly.

Underneath that, they added a small note saying, “Today I must sell…”, followed by the specific number of copies they had to sell that day in order to solve their big problem. As they sold more magazines throughout the day, they could change the numbered cards, and those cards were salient enough to catch buyers’ eyes.

With this, the buyers felt like they were really making a difference, moving the vendors closer to their goals, not that they were just being asked for money willy-nilly.

Diagnosing COPD

Behavioral consultancy Mindworx teamed up with a global pharmaceutical company to come up with a communication strategy to increase the number of general practitioners (GPs), who referred patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) symptoms to a pulmonologist.

One of the reasons why COPD (which is soon likely to become one of the top 3 leading causes of death in the world, according to WHO) is still widely underdiagnosed is stereotyping.

Representativeness bias meant doctors simply failed to think of COPD when a slim woman entered their office.

One of the stereotypes GPs have is that the disease is more prevalent in overweight older male smokers than in petite non-smoking women (which is not true – it actually affects women more). Representativeness bias meant doctors simply failed to think of COPD when a slim woman entered their office.

So, the campaign used stories of specific female patients who hadn’t been diagnosed in time, which had had a severe impact on their life. Leaflets and newsletter included a clear call-to-action: “If you suspect COPD, refer the patient to a pneumologist.” ensuring that COPD would come to mind and not be overridden by more common respiratory diseases such as asthma.

Sales of Porsche

You don’t need to be a reader of high-brow articles such as this one to know a person has to test drive a car before they buy it. Duh. Salespeople at Porsche knew this consciously too, but their subconscious beliefs, such as the notion that older people don’t drive fast cars and single women can’t afford a Porsche, prevented them from offering test drives. This translated into sales results which left a lot to be desired.

Observation research found that only customers who “looked like Porsche people” were offered test drives. We can easily picture the staff’s rationale going something like this: “You don’t match my self-created criteria of what a Porsche buyer should look like. You’re just here for a ride but have no intention to purchase. Therefore, it’s a waste of time to offer you a test drive.” This and two other preconceived beliefs blocked staff from taking actions they knew were important for an outcome.

Workshops helped salespeople overcome these biased beliefs and replace them with other potential beliefs about the importance of an equal approach.

It’s fair to say change didn’t happen overnight. But slowly, through repetition, sales-floor shadowing, encouragement, and buy-in from all levels of leadership, salespeople began to offer test drives more naturally. The intervention group exceeded regional standards by offering test drives to 90% of potential buyers, and that and other interventions increased sales by 28%.

The intervention group exceeded regional standards by offering test drives to 90% of potential buyers, and that and other interventions increased sales by 28%.

How to use it in business

Representativeness bias and staff

Find out if your sales team is under its influence and what impact it has on their behavior. Also, ask “Who is your most valuable customer?” It may not be the “picture perfect one”. Be ready to challenge any preconceived notions.

For example, high-end retail stores are quickly learning that female customers in athleisure wear actually have a lot more buying potential than they used to give them credit for – often even more than let’s say smartly dressed women. The stereotype of wealth that is shown off by wearing swanky clothes just no longer holds water.

Representativeness bias and hiring

Just because someone fits the stereotype of a great accountant does not mean they have the best skill set for the job. Sometimes even a name can induce resume bias.

Anonymize or jointly compare CVs so that you concentrate on the information that matters as advised in the Behavioral Insights Team report. They also conclude that structured interviews can be more effective than unstructured ones to gauge the best fit (even though the difference may not be as strong for certain types of interviewers).

Representativeness bias and your product

Consumers may infer a relatively high product quality from a store (generic) brand if its packaging is designed to resemble a national brand.

Find out what stereotypes and prejudices are linked to your product or service and what associations your messaging or packaging triggers in customers. For instance, it was found that consumers may infer a relatively high product quality from a store (generic) brand if its packaging is designed to resemble a national brand.

Summary

What is representativeness bias?

The representativeness heuristic is an automatic mental shortcut we use to make assumptions through stereotyping.

How to avoid representativeness bias?

Think like a statistician and learn more about logical thinking. Consider the sample size when assessing the probability of an event and take time to slow down in instances you feel you might be relying too much on representativeness.

How to use representativeness bias in business?

Become familiar with stereotypes that you (and your staff) may have about certain customers and how these influence the service the customers receive as a result. Aim to treat each with the same amount of care.

Deliberately anonymize CVs when assessing them (have someone remove the picture and name beforehand). When interviewing, be aware of a mental image of the perfect candidate and scrutinize any instances of you favoring people who look the part.

Learn more about stereotypes tied to your product or the industry as a whole and become familiar with preconceived notions that you may have to address.