Finding the Chaos in Order: How to Write Shareable Content According to Psychology

Was your last Facebook post a flop? Is your content strategy based on a whim? Does your newsletter get embarrassing engagement rates? Well, we’ll let you in on a little secret… There’s a science to creating shareable content and it all starts with being ‘interesting’.

In this article you’ll find:

- What exactly makes something interesting based on psychology;

- The science behind a reader’s AHA moment, a.k.a. intent to share; and

- Action-based tips on how to write better content.

Scroll through your newsfeed and you might stumble upon a simple, and even stupid, piece of content that has 100s of 1,000s of shares. How is this even possible? Why did so many people click the share button, RT, or even take the time to post a comment?

The answer is because it was interesting. Not interesting like “personal, self-serving kind of interesting” (e.g. piña coladas, getting caught in the rain), but interesting in the sense that it made every single person it engaged go: “AHA! That’s interesting!”

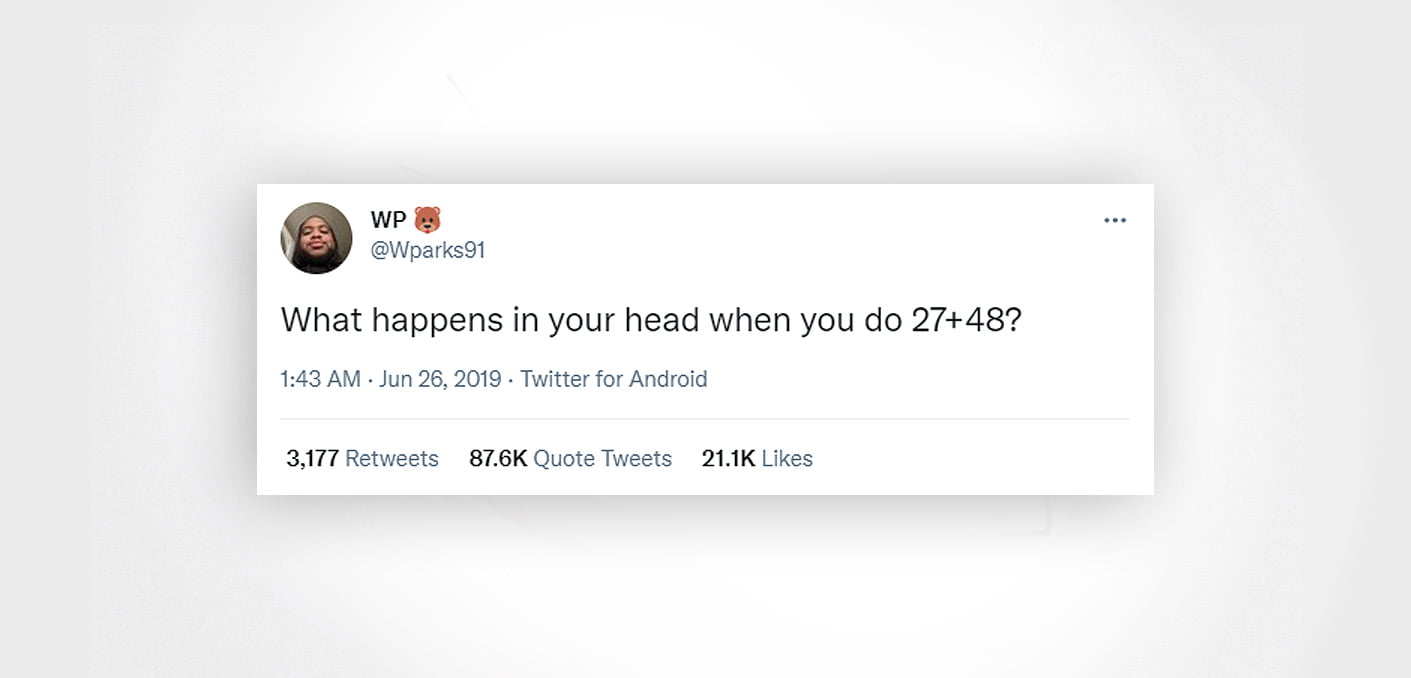

Take this viral math tweet as our first example.

Source: Twitter

It’s an elementary math problem that will always result in 75. But the fascinating thing is how different people get to the same answer.

- 20+40=60 , 7+8=15 , 60+15 = 75

- 27+50=77 , 77-2 = 75

- 30+48=78 , 78-3 = 75

- 8+7=15 , carry the 1 , 4+2+1=7, = 75

- 27-2 = 25 , 48+2 = 50 , 50+25 = 75

- 27+3=30 , 48-3=45 , 45+30 = 75

So what? What makes that so interesting? And why does the fact that people think about the function of numbers in different ways spark such a viral, shareable post?

People share things that are interesting

Duh! Shall we move on?

Oh wait, there’s more. Much more, actually. It’s called the Sociology of Phenomenology, a research paper published by sociologist Murray Davis in 1971 is considered to be one of the most influential articles in Management Studies and has been a standard reading requirement in most doctoral management programs for the past 50 years.

Davis’ research states that “interesting theories are those which deny certain assumptions of their audience, while non-interesting theories are those which affirm certain assumptions of their audience.”

People share ideas that challenge an old truth or that constitute an attack on the reality they’ve taken for granted.

From this research came The Index of the Interesting, a format for writing interesting propositions divided into 12 logical categories. These 12 principles relay the core concept that “what seems to be X is in reality non-X or what is accepted as X is actually a non-X.”

People share ideas that challenge an old truth or that constitute an attack on the reality they’ve taken for granted. In this case, math. 1+1=2. End of conversation. But actually, people think of math and numbers in a variety of different ways. Perhaps, this is why Common Core math sparked so much controversy and why this silly math question has been replicated and shared hundreds of thousands of times on social media.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

Understand this and you, as a marketer and content creator, will create more shareable content.

So how does psychology define ‘interesting’?

Our instincts say that the definition of ‘interesting’ is highly subjective. In many cases, that’s true. Take organized sports, for example. Some of us live and die for sports, others, meh, not so much. But there are some common truths rooted in human psychology that can make a fact about hockey very interesting to almost anyone.

FACT: Statistically, you’re far more likely to get drafted by the NHL if you’re born in February instead of November. The NHL has a selection bias that significantly favors kids born in the first quarter of the year.

The science-based secret to creating shareable content is finding interesting elements in your content.

Something that appears to be random (a birth month in hockey drafting) is actually an organized phenomenon. Something that appears to be universal (numbers) may actually be individual. Now that’s interesting!

The Sociology of Phenomenology defines several principles that make a theory or an idea interesting. They are all related to the element of “AHA!” Thus, the science-based secret to creating shareable content is finding these interesting elements in your content.

Let’s start by looking at five of these principles and pairing them up with easy-to-implement, trustworthy tips that you can try straight away in your own content strategy.

1. Organization: What appears to be organized is actually random

Or vice versa. What appears to be totally random is, in fact, organized.

That’s the NHL draft example. One assumes that a birth month is a totally random factor when determining first-round draftees for the National Hockey League. But as it turns out, 40% of Canadian-born, first-round NHL draftees were born in the first quarter of the year. Yet, players born in the first quarter make up less than 25% of Canadian All-Star and Olympic team members, implying that this age bias does not correlate with actual talent.

The organization principle of interest:

- What seems like a random (unstructured) phenomenon is, in reality, an organized (structured) phenomenon.

- What seems like an organized (structured) phenomenon is, in reality, a random (unstructured) phenomenon.

Even crazier, all this data is widely known by those selecting draftees. It’s no secret (anymore) that the NHL has a draft bias in favor of first-quarter-born kids, yet this practice persists.

How to apply this principle to content:

Find an example of something highly organized and structured within your industry, product group, or sphere of influence. What’s the best organizational practice you can adopt and then flip on its head?

Try this:

- Think of a format, structure, or process that is tightly upheld in your industry. Something highly structured and considered as standard best practice, such as SWOT analysis in marketing or a Purchase-to-Pay (P2P) process in accounting. Find a hole in that organizational structure, something that demonstrates the randomness of perceived order. Is there randomness to a SWOT analysis that can better evaluate your competitive landscape? Can you dig up anything from Gartner and the Magic Quadrant? Is the organizational structure of P2P the core of its success, or is it random? Is there something that process mining can reveal?

- Find that sweet spot of hypocrisy for your industry and let it out all hang. Find the random in the organized or the organized in the random.

2. Composition: When true talent is just 10,000 hours away

The composition principle gives us that AHA moment because what seems to be made up of multiple elements is in reality made up of a single element. Take, for example, talent. Exceptional talent cannot possibly be based on a single element. How could Mozart, Kobe Bryant, Bill Gates, and the Beatles all achieve greatness by the same means?

The composition principle of interesting:

- When a phenomenon that seems to be made up of multiple elements is, in reality, made up of a single element.

- When a phenomenon that seems to be made up of a single element is, in reality, made up of multiple elements.

Best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell convinces readers in his book Outliers that the single element to exceptional success is practice. Put in 10,000 hours of focused practice and you’ll become an expert in your field. There are a billion other roads that lead to talent, but if you want something unconditionally, practice for 10,000 hours and it’s yours.

How to apply this principle to content:

The composition principle relays ‘interesting’ by depicting something complex as simple, or something simple as complex. Is there a simple truth in your industry that everyone has overlooked or forgotten about? Is there a process that has become so complex but there is actually one simple underlying principle, law, or truth to it?

What’s a complex problem everyone in your industry is facing? Is it employee retention rates for HR professionals? Or is it figuring out how to create easy, shareable recipes for food bloggers? Can you break down this complex problem into a singular root cause? Is there actually 1 simple reason why people quit their job? Does it really matter if you measure ingredients precisely when following a recipe?

Try this:

- What simple rule of thumb does everyone in your industry consider to be true?

- Explore this perceived truth and see if there’s a complex backstory or reasoning behind it. What makes this rule of thumb your industry’s simple truth. Can you break this ‘truth’? Is the customer always right? Does data sometimes lie? Should you really try before you buy?

3. Function: When something works when it shouldn’t

Smacking an electrical device to make it work. Face yoga. The mother who self-hypnotizes into painless childbirth. A thermomix that makes butter chicken and banana bread. You rub your belly and pat yourself on the head at the same time. Bulletproof coffee. Bacon donuts. Has the world gone mad? None of these things should work, but they do.

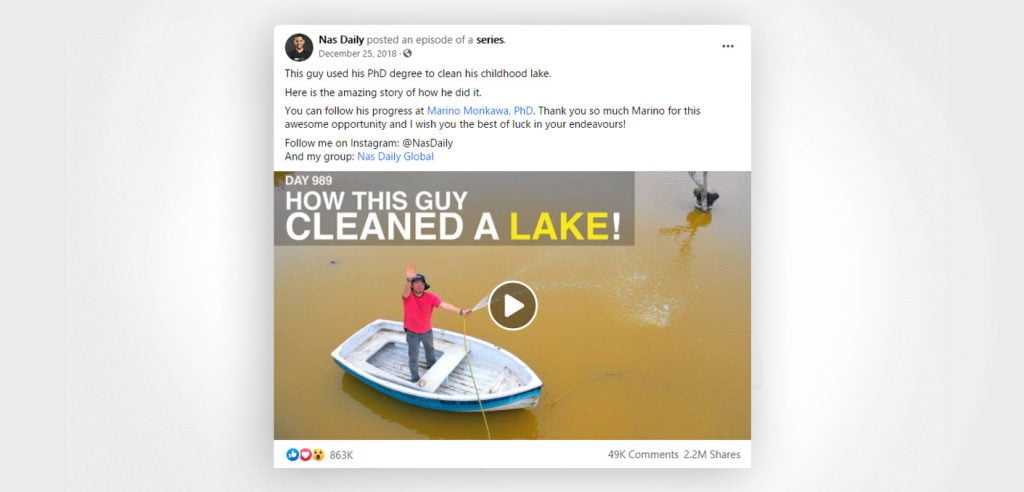

The function principle is essentially the basis for most Buzzfeed food posts — 27 Fucked Up Food Combinations That Shouldn’t Work But Do. It’s also the core content strategy of NasDaily, the highly successful viral video platform that tells stories of people succeeding against all odds. This video with over 100 million views tells the unlikely story of a man who transformed a polluted lake into a bird and human sanctuary in a matter of months using nanotechnology.

Source: Nas Daily Facebook

The function principle of interesting:

- What seems like a phenomenon that functions ineffectively is really a phenomenon that functions effectively.

- What seems like a phenomenon that functions effectively is really a phenomenon that functions ineffectively.

When something bound for failure actually succeeds, that’s interesting. Or vice versa. When something destined for success actually fails. Like when hitting the crosswalk button a gazillion times fails because it’s in recall mode or is broken just like 90% of New York City’s crosswalk buttons.

How to apply this principle to content:

Most industries have DIY mavericks. People who set out to fix their own problems by any means necessary, with or without your product or service. Don’t be afraid to talk about these outliers and how they achieved success through the strangest of means.

You can approach content structure in two different ways depending on what your content goals are. Sales CTA: This is how they (the DIY mavericks) succeeded against all odds, but this is how our product or service makes that success way easier to achieve. Storytelling and Community Building: A genuine success story for our industry that’s worth sharing.

Try this:

- Find the DIY mavericks, concepts, or companies in your industry or sphere of influence that succeeded against all odds. Such as Wim Hof the Iceman, Beyond Meat, Ron Clark Academy, or entrepreneurs building hotels out of trash.

- Tell their story and identify how their flawed or bizarre approach to solving a problem actually worked.

4. Generalization: When the crowd is smarter than you

Ever been to a county fair? If you have, you’ll know the atmosphere is one of debauchery, joy, and downright fun. It’s no IQ competition. So would it pique your interest to know that a random crowd at a fair is likely to have better judgment than you? It’s called the wisdom of crowds and it was explored in a 2014 book written by James Surowiecki.

Take something that one part of the world considers universal and flip it to show that it's a local phenomenon.

The opening of the book describes the crowd at a county fair that accurately guesses the weight of an ox more precisely than the estimates of most individual fair-goers. Turns out, there’s a method to the madness in crowd psychology. The theory goes that a diverse group of independently thinking individuals is more likely to make better decisions than individuals or even experts.

The generalization principle of interesting:

- What seems like a local phenomenon is, in reality, a general phenomenon.

- What seems like a general phenomenon is, in reality, a local phenomenon.

That’s the generalization rule. What seems to be a local or one-off phenomenon (the smart crowd at a county fair) actually applies to the way the world works at large (the wisdom of crowds).

How to apply this principle to content:

This is a fun and simple principle that the viral masters at Buzzfeed use a lot in their content creation. They take something that one part of the world considers universal (having a dryer in your house) and flip it to show that it’s a local phenomenon.

The most viewed Buzzfeed article of 2020 is about everyday things Americans do that non-Americans find bizarre. What seems to be everyday life for everyone — writing dates like MM/DD/YYYY — is in fact a localized habit.

Try this:

- Think of your target audience in geographical or cultural terms. What’s your dominant culture or geolocation?

- Identify a common truth that almost everyone in that culture or location takes for granted (within the context of your industry). Breakfast is meant to be fast and cold (FMCG). Everyone drinks coffee-to-go in the mornings (cafés or canned ice coffee drinks). Everyone has their laundry machine in a closet or small laundry room (for appliances).

- Show that truth is a local phenomenon, not a general phenomenon. Indians pour hot milk on cereal. Italians widely reject coffee-to-go while chaiwallahs in India will serve tea to passengers through the window of a moving train. Many Europeans have a laundry machine in their kitchen.

5. Evaluation: When stealing money is good

The best way to apply the evaluation principle of interesting to your content is to find good and bad phenomena within your space and find the yin to that yang.

When a powerful corporation like Nike approaches you with a sponsorship deal you follow orders. Or at the very least, you don’t take the money and go on an all-expense-paid vacation around the world with your buddy Max. Or do you?

The #Makeitcount video by Casey Neistat with 31 million views on YouTube follows an adventurer and his buddy around the world in 10 days as they plow through sponsorship money from Nike.

What seems bad — taking sponsorship money and traveling the world instead — is actually good. Or what seems like a good phenomenon is, in reality, a bad phenomenon. Looking at you, almond milk and recycling.

How to apply this principle to content:

There are two sides to every coin when it comes to products or industries. Some do (mostly) good, and others do disproportionately bad. The best way to apply the evaluation principle of interesting to your content is to find these good and bad phenomena within your space and find the yin to that yang.

The evaluation principle of interesting:

- What seems like a bad phenomenon is, in reality, a good phenomenon.

- What seems like a good phenomenon is, in reality, a bad phenomenon.

Try this:

- Identify the obvious good and the obvious bad within your industry. Compostable goods vs. overconsumption (packaging). Crowdsourced funding vs. lack of government action (charity). Pollution vs. a source of the material (oil and gas).

- Find the nugget of good in the bad and the stain of bad in the good. Instead of reducing consumption, recyclable or compostable packaging makes consumers buy even more. Crowdsourced platforms help the needy, but don’t address systematic problems. The oil industry pollutes, but they also make medicine and everyday life possible.

This article is only one of two parts. Get more actionable insight into the science of interesting and how it can help you write better content here.

Key Takeaways

- The science of creating shareable content is based on psychological principles developed by sociologist Murry Davis.

- The 12 principles are rooted in a singular concept: “what seems to be X is, in reality, non-X or what is accepted as X is actually a non-X.”

- Apply these principles to content creation by identifying commonly held beliefs within your industry and finding the flip side.

- Use the story-study-lesson methodology popular in science fiction writing to build your case. Challenge your audience’s beliefs respectfully, because the goal is for them to consider, explore, and accept your idea and not be scared of it.