A Guide to Discounting: Should You Frame Discounts in $ or in %?

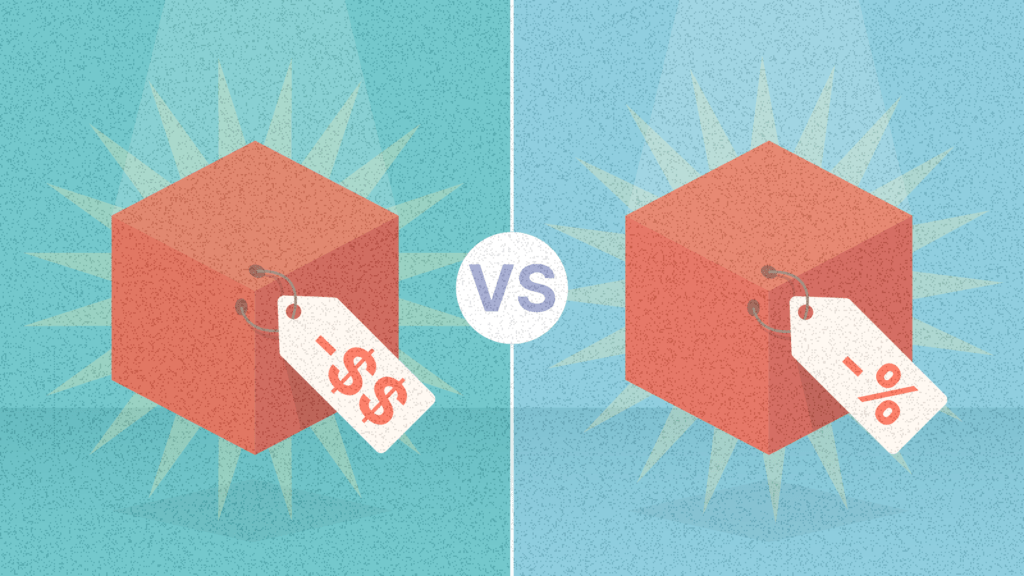

The question of whether to frame discounts as a nominal value or as a % off has bothered marketers for a long time. But scientific evidence gives us some answers. Learn when it’s better to use % off and when to use $ off.

In this article, you’ll discover:

- What’s going on in your customer’s heads when they’re faced with discounts;

- Whether it’s better to frame your discounts as % or as $ off;

- What the factors are that influence the discount perception; and

- How to make sense of it all and adjust your discounts in the optimal way

One of the greatest findings of consumer psychology is that the value that customers perceive is not objective, but can be influenced by many factors. Customers are vulnerable to many cognitive biases that can nudge them to buy or not to buy. When it comes to discounts, the same holds true.

Before jumping to pricing and discounts themselves, you need to understand what’s happening in your customers’ heads when they think about numbers. Picture the following situation: You’re standing in front of two containers. The small one contains 2 red marbles out of a total of 10. The large container contains 19 red marbles out of a total of 100. You get to choose one of the containers, out of which you will draw one marble. If the marble drawn is red, you win a prize.

Of course, you have to pick without looking and the containers are shaken up before you draw. Which one of the containers should you draw from to maximize your chances of winning?

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

And an even more important question – what the heck has this got to do with pricing? Actually, a lot. If you picked the larger container with 19 red marbles, you fell for so-called ratio bias. Research shows that more than 60% of participants pick the larger one as well. If you chose the smaller one, congratulations! You picked the one with a higher probability of winning.

The value that customers perceive is not objective, but can be influenced by many factors.

So why is that? Why do people fall for problems like this if all it requires is to spend a minute to think about it? Well, that’s why – because it takes a minute to think about it. And thinking is hard – it not only costs us time, but also energy.

That’s why we evolved in a way that allows us to save time and energy, and instead of thinking hard about everything in every situation, we use subconscious shortcuts (heuristics) – intuitions that allow us to solve simple problems quickly.

That’s why in the example above, people don’t think about it and instead, they judge the absolute value they see – 19 is a bigger number than 2, therefore they pick the larger container.

Believe it or not, it’s very similar to your customers. Multiple studies have looked at how the ratio bias affects their price perceptions – specifically, how they perceive differently framed discounts. They offered customers multiple products and let them judge which discount seemed like the better deal – either a discount in % or in $.

A word of caution here – all of the studies we mention from now on worked with $, € or £. All of those have a similar value, so the results can only be generalized for your situation if you live in a country with one of these currencies. The effects may differ with currencies such as PLN, CZK, INR or any other currencies in which the absolute values are much higher.

Discount perception depends on the price of the product and the amount of the discount

The results of these studies were not that straightforward, but the general trend was that, as in ratio bias, people overestimated the larger numbers.

If the discount was framed as a percentage (e.g. 25% off an $80 item) participants perceived it as a better deal than the same discount framed in $, when the absolute value in $ was a lower number (e.g. $20 off an $80 item) and vice versa. However, there were some situations where this was not the case, and that depends on multiple factors.

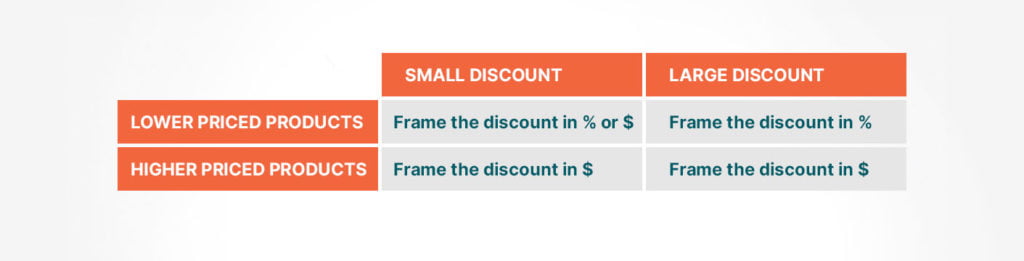

There are multiple situations that may take place depending on your product and the discount you’re offering. To get a clearer picture, you can see these categories in the table above, together with general advice on the discount framing. In general, you can offer:

- A cheaper product with a small discount

- A cheaper product with a large discount

- An expensive product with a small discount

- An expensive product with a large discount

Of course, what you consider a cheap and expensive product might differ, as well as what constitutes a small and large discount and everything in between. But the majority of research in this area primarily focuses on these 4 categories, with cheaper products being, for example, potato chips or cola and more expensive ones usually electronics. A small discount is usually considered a 10% discount, while a large one ranges between around 30 to 40%.

Let’s start with lower-priced items. In line with the example of ratio bias above, a discount in % is generally more effective here. As the number is higher in percentage (e.g. 20% discount for a bar of chocolate) than in absolute price (e.g. $1 discount). When faced with the discount in %, customers perceived it as a better deal and were more likely to buy.

However, the studies showed that the amount of discount can be a factor here. When the discounts were small, both % and $ worked equally well.

When it comes to higher-priced items, the trend seems to be the opposite. The discount in $ seems to work better here, with the discount amount having minimal or no effect. Again, that’s likely because, with expensive products, the discount in $ (e.g. $200 off a $1000 smartphone) is expressed in a higher number than in % (“just” 20% off).

For items more expensive than $100, go with the $ discount

Okay, let’s make this a bit clearer. Marketing Professor Dr. Jonah Berger, author of the book Contagious: Why Things Catch On, offers an easy way to remember these complicated research results. He calls it the Rule of 100 (but again – it only applies to currencies such as $, €, £ or ones with similar value).

It’s a simple heuristic – does your product cost more than $100? Go with a $ discount. Is it less than $100? Go with a % discount.

Does your product cost more than $100? Go with a $ discount. Is it less than $100? Go with a % discount.

The rationale is straightforward here. With two-digit prices, the absolute value of the % discount is higher than the $ discount. If a $20 t-shirt is discounted to $15, it’s better to frame it as 25% off, than $5 off because 25 > 5.

However, with three-digit prices ($100 and above) it’s the other way around. For $200 headphones, it’s either 25% off or $50 off. And 50 > 25.

Of course, you can expect that the effect will be less visible around the $100 mark (a $95 product vs a $105 product). But as a general rule of thumb, the rule of 100 should make your discount decisions a bit easier.

Key takeaways:

- Customers overestimate large numbers. People are not used to doing complicated calculations, so they judge discounts intuitively. The higher the number, the better.

- With low-priced products (below $100), it’s better to frame discounts in % than in nominal value. The absolute value of the discount is higher when framed as a percentage.

- With high-priced products (above $100), it’s better to frame discounts in nominal value, as the absolute value of the discount is higher that way.