The IKEA Effect – Everything You Need to Know

The IKEA effect describes a common bias that happens when we spend effort on a product or project. Here’s everything you need to know about this behavioral economics concept.

Article content:

The IKEA effect defined

The IKEA effect describes a cognitive bias that happens when we work to acquire a product, complete a project, or finish a creation. It says that we tend to overvalue things that we are involved in making. Michael Norton et al, who coined the term “IKEA effect” in their 2012 paper, define this effect as simply an “increase in valuation of self-made products.”

Have you ever felt like no one truly appreciates your carefully put-together outfits? Or that no cake tastes better than the one you’ve baked yourself? Perhaps you’ve told a child that their artwork was amazing just so that you didn’t hurt their feelings?

How does the IKEA effect work?

Situations like these expose our tendency to increase our valuation of products or outcomes when we labor for them. Stressing that new office wardrobe may distort your perceptions of how much other people are likely to notice. Working hard for your dessert could set you up to enjoy it even more. And by the time a child has finished their painting, they may see no difference between their art and that of Picasso’s.

Labor alone is enough

What makes the IKEA effect interesting is that it says labor alone is enough to increase a person’s valuation of a product. That means the effect still applies in situations where added effort isn’t fun or objectively worthwhile.

Many people enjoy the process of cooking dinner from a meal kit delivery service. Others will impress their friends with their newly customized sneakers. Putting in the extra effort to produce these products adds value beyond the retail price.

Discover ground-breaking ideas and fascinating solutions.

But according to the IKEA effect, even when you don’t receive additional benefits from working for a product, you’re still likely to increase your valuation of it.

Even when you don’t receive additional benefits from working for a product, you’re still likely to increase your valuation of it.

That’s why Norton chose to name the effect after the famous Swedish furniture company. As anyone who’s thrown an Allen key across the room after wrongly assembling a new dining table for the fifth time knows, building flatpack furniture isn’t an inherently enjoyable task.

Why does it work?

If humans were perfectly rational creatures, we’d expect products to cost less when we’re required to help produce them. If our effort is needed to finish constructing furniture, preparing meals, or explaining to the barista exactly how we like our coffee, we should demand a discount for our efforts, right?

The IKEA Effect

When people put effort into something, it becomes more valuable to them than its objective value. Make your customers contribute or at least give them the feeling they contributed.

The IKEA effect says the opposite: when people add their labor to products, they also add to their valuation of those products – meaning they’ll happily pay more.

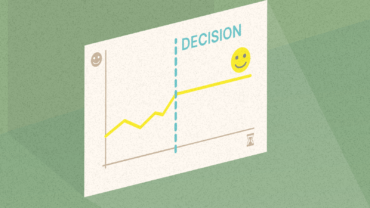

One condition that Norton’s paper found for the IKEA effect is that the “successful completion” of labor is essential. So the effect will only appear in situations where a person feels satisfied with the outcome of their work. If the instructions for your dining table are too confusing, or your coffee arrived with the wrong type of milk, you’re unlikely to overvalue it.

Three cognitive principles behind the IKEA effect

Three major cognitive principles help to explain the IKEA effect. These are the need for competence, the concept of effort justification, and the endowment effect.

1. Competence

When we manipulate objects around us – especially when we complete a task – it can help to satisfy a fundamental need to control the world around us.

Legendary behavioral scientist Albert Bandura demonstrated this effect in his 1977 paper when he showed how successfully completing tasks increased people’s feelings of competence and control.

- When we contribute to the completion of a task or product, a cognitive-behavioral need is satisfied.

2. Effort justification

Effort justification is a widely recognized cognitive bias where people elevate the value of outcomes they struggle to achieve. Nobody likes to think they’ve spent time and energy in pursuit of a worthless goal, so we tend to view our aims as more valuable than they actually are.

There are clear ties between effort justification and the IKEA effect: both describe situations in which our need to feel good about our actions affects the way we view products or outcomes. Some studies have even shown effort justification in animals like rats and birds.

- It’s satisfying to feel that our hard work creates valuable results.

3. The endowment effect

The Enddowment Effect

When people own something they value it beyond its objective value. Frame your message in ways that make customers feel like they already own your product, discount, or benefit.

The endowment effect is another similar bias that makes us predisposed to overvalue things associated with ourselves.

Whether it’s due to sentiment, length of ownership, or simply a feeling of connection, being tied in some way to an item is likely to distort our estimation of its worth.

The difference between the two concepts is that the endowment effect suggests that feeling connected to a product increases subjective value, while the IKEA effect suggests that spending effort on a product increases subject value. Both can occur at the same time.

- Feeling a sense of ownership over an item can make you value it more highly.

What impact can it have?

The extra sense of value that the IKEA effect creates can be leveraged by companies to make customers pay inflated prices for products. If you play a role in assembling, customizing, or designing something that you buy, you may unknowingly (and happily) pay more than it’s worth.

The IKEA effect can also impact our personal and work lives. It means we’re vulnerable to distorted perspectives whenever we work hard on a project. This risks making us bullish about our work in comparison to others.

This consequence was recorded in Norton’s study when “participants saw their amateurish creations…as similar in value to the creations of experts, and expected others to share their opinions.”

The IKEA effect might be at play when:

- A colleague who’s worked really hard on a project can’t acknowledge that it’s not producing the expected results.

- People aren’t willing to pay the prices you’ve set for the crafts on your Etsy store.

- A parent believes that their child is always the best in their class.

IKEA effect experiments

Boxes, origami, and lego

In Norton’s paper, participants were asked to construct three types of objects: IKEA cardboard boxes, origami cranes or frogs, and Lego sets.

After building them, participants were told to estimate the value of each object in the group, including their own, and to enter bids for the objects that represented their valuations. With the origami, participants were also told to consider a model made by an origami expert.

The experiments in Norton’s paper found that participants were likely to value any object they played a role in creating more highly than those made by others. Some participants increased their valuations of self-made items so much that they rated them as comparable to an expert’s version.

Participants were likely to value any object they played a role in creating more highly than those made by others. Some participants increased their valuations of self-made items so much that they rated them as comparable to an expert’s version.

Running the experiment with several types of items helped the researchers to differentiate this effect from similar concepts such as the endowment effect. Using something boring like a box with a strict instructional guide and no opportunity for customization helps to show that labor alone is sufficient to increase a sense of value. Despite being confronted with a range of identically assembled cardboard boxes, participants would rate the one they made as more valuable than the others.

Social “hazing”

In an old 1959 paper from the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Aronson and Mills demonstrated something similar to the IKEA effect in social settings.

In the study, participants were asked to join discussion groups. One set of participants joined their group with ease, while others were required to undergo difficult or embarrassing initiatives to join.

When the discussion groups ended, and participants were asked to rate how they valued being a member of their group, those who were required to persevere, or who experienced difficulty in joining, valued their memberships more highly than those who did not.

Kids and vegetables

Since Norton’s study, two papers have tested the IKEA effect by looking at whether children are more likely to enjoy vegetables if they’re involved in cooking them.

In a 2019 paper published in the British Journal of Psychology, Radtke et al. tested whether “parents’ involvement of their children in meal planning and preparation is positively related to vegetable intake, mediated via liking vegetables.”

They found that involving children in the preparation of healthy meals improved their liking of vegetables and vegetable intake, and had no effect on adult preferences or intake.

However, in a similar 2021 study, Raghoebar and Van Kleef couldn’t replicate the IKEA effect in children who were involved in the preparation of vegetable-based snacks.

History of the IKEA effect

The IKEA effect was named by Michael Norton, Daniel Mochon, and Dan Ariely in 2011 and published in a 2012 paper in the Journal of Consumer Psychology. It’s called “The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love.”

Norton et al claim to demonstrate the IKEA effect via a series of experiments in which participants make, rate, and barter for cardboard boxes, origami, and Lego models. The paper also explores the psychology behind the IKEA effect, as well as several examples of the effect in commerce, such as this one featuring Betty Crocker cake mixes:

“When instant cake mixes were introduced in the 1950s as part of a broader trend to simplify the life of the American housewife by minimizing manual labor, housewives were initially resistant: The mixes made cooking too easy, making their labor and skill seem undervalued. As a result, manufacturers changed the recipe to require adding an egg. While there are likely several reasons why this change led to greater subsequent adoption, infusing the task with labor appeared to be a crucial ingredient.”

Manufacturers changed the recipe to require adding an egg. While there are likely several reasons why this change led to greater subsequent adoption, infusing the task with labor appeared to be a crucial ingredient

As many have noted, fresh eggs do tend to make better cakes, and powdered eggs are generally considered an inferior ingredient – so the IKEA effect likely isn’t the whole story here.

What this example does show, however, is that there was a history of marketing professionals noticing the IKEA effect on consumer behavior and harnessing it in product design, long before it was formally defined by Norton’s paper.

To learn more about The IKEA effect, check out the article from our friends at Nova Awareness. Their main focus is Economics but also other topics such as Finance, Politics, Environment, Innovation, and Education.

How to avoid the IKEA effect?

Norton’s experiments found that “labor increases the valuation of completed products not just for consumers who profess an interest in “do-it-yourself” projects, but even for those who are relatively uninterested.”

Labor increases the valuation of completed products not just for consumers who profess an interest in “do-it-yourself” projects, but even for those who are relatively uninterested.

That means you may have been subject to the IKEA effect even if you don’t consider yourself somebody who’s into building or finishing your own products.

So, how can we avoid the IKEA effect or learn to notice when it might be happening? Here are two strategies:

- Get a second opinion. The IKEA effect describes how the amount of effort we put into a product, service, or transaction can affect our sense of value. Asking an unbiased third party for their valuation is therefore a good way to avoid a bad valuation.

- Ask for feedback. Navigating around the IKEA effect in our personal lives requires being open to feedback. When you’ve worked hard on a task and it becomes difficult to stay impartial, get some trusted opinions to help broaden your outlook.

Do you always need to avoid it?

Being unable to see the true value of your work because of the effort you’ve invested into it is not a helpful cognitive bias.

But sometimes, it’s nice to value something a little more because of the effort you spend – even if that item isn’t seen in the same light by others.

For example, there’s nothing wrong with thinking your child is the smartest in their class because you’re heavily invested in raising them.

Likewise, at times when it’s useful to increase your valuation of something (such as with kids and vegetables), it’s helpful to know that investing labor may make you see things in better terms.

Examples of the IKEA effect

Earning discounts

Sale events and promotions are a universal tactic for marketers. But cutting the price of products can risk undermining their perceived value to consumers, who may question their quality or the motivations of sellers.

To avoid this, some companies employ the IKEA effect in the form of earned discounts. An earned discount is when a customer is made to perform some task or action to become entitled to a promotion.

In line with the IKEA effect, people often value discounts more if they have to “earn” them. Examples of earned discounts include loyalty points, early bird deals, and George Lois’ famous Renault Band-Aids.

Meal delivery kits

Following in the footsteps of Betty Crocker in the 1950s, many modern food startups have discovered that customers prefer to participate in the preparation of their meals.

Meal kit subscription services, in which subscribers receive a weekly box of pre-portioned ingredients to prepare home-cooked meals, are an obvious example.

With the meal kit industry valued at over 5 billion dollars in the US alone, it’s no surprise that new brands are popping up every month. Industry leaders like HelloFresh and Blue Apron go big on marketing the benefits of “food made from scratch in the comfort of your kitchen.”

Meal kit services hope that the customer labor required to prepare their meals will encourage brand loyalty. Customers' feelings of accomplishment when they complete recipes may also become associated with the company.

Meal kit services hope that the customer labor required to prepare their meals will encourage brand loyalty. Customers’ feelings of accomplishment when they complete recipes may also become associated with the company.

Home improvement projects

Painting the bedroom, tiling the bathroom, or sanding the hall floor are labor-intensive projects that can trigger the IKEA effect in budding DIYers. Those who work extensively on home improvements may begin to bias their estimation of property value.

Over-valuation of home renovations can become more extreme when people build to their personal specifications – one person’s dream wallpaper or kitchen counter can be another’s interior design nightmare.

Examples like these show how the IKEA effect can combine with peoples’ personal tastes to create subjective valuations that stray far from market value.

Customizable clothing

Many companies offer products with customizable features, allowing consumers to tailor products to their tastes and needs.

These aren’t always strict examples of the IKEA effect, as customization can create legitimate additional value – maybe it’s social status, rarity, personal enjoyment, or something else.

But to the extent that a consumer overvalues a product due to the fact that they spent effort in producing it, the IKEA effect may be at play.

One early and successful example is Nike By You, a customization app for Nike shoes launched by the company in 2000 – originally under the name Nike ID. Using the service, consumers can alter the materials and colorways of shoes to a surprising degree of detail.

Taking the time to pick the exact shades and color combinations of your new sneakers may cause you to develop a stronger connection to them, and make you more likely to buy.

Limited release products

Scarcity

When an object or resource is less readily available (e.g, due to limited quantity or time), we tend to perceive it as more valuable.

Another common marketing technique that makes partial use of the IKEA effect is limited product runs.

Often, companies will restrict access to their products by producing an insufficient quantity or only selling to consumers who have registered for membership. Others will create the appearance of scarcity by withholding their stock.

Also known as the Scarcity Principle, it can be seen in action on most online booking companies, such as hotel and flight providers. These sites often alert consumers when their chosen flight is filling up, a price discount is ending, or hotel rooms are running out.

How to use the IKEA effect in business

Many companies leverage the efforts of consumers in the design, manufacturing, or marketing of their products.

Focus groups, industry influencers, and brand evangelists are just some of the ways in which people can become “co-creators” of product value.

For the IKEA effect to work, consumers have to be aware that they are putting in effort, and they can’t be made to work too hard, or fail to successfully complete a task.

The challenge for marketers who want to use the IKEA effect is to convince consumers to consciously engage in tasks that are hard enough to require effort, but not so hard that they risk failure.

So, the challenge for marketers who want to use the IKEA effect is to convince consumers to consciously engage in tasks that are hard enough to require effort, but not so hard that they risk failure. Here are three examples of how this might be achieved:

Insert simple tasks and activities into the buying pathway

Giving consumers an active role in the buying process may encourage greater investment in products. Whether they’re required to press buttons, tweak their order, or organize their cart, the IKEA effect says that simple tasks help consumers stay interested.

Insert simple tasks and activities into the buying pathway

Giving consumers an active role in the buying process may encourage greater investment in products. Whether they’re required to press buttons, tweak their order, or organize their cart, the IKEA effect says that simple tasks help consumers stay interested.

- Make product images and descriptions interactive by using surveys and dynamic models.

- Let consumers compare products with filters and malleable tables.

- Even the simple process of setting up user accounts may lead to increased engagement.

Bring clients into the design process

In B2B, the IKEA effect can be triggered by involving clients as much as possible. If a client feels like they’ve collaborated on a project, they may value its results more highly.

- Create opportunities to demonstrate how client ideas and opinions have been heard and taken into account during production.

- Position client input as substantive and valuable, even if their real input is limited. This will help to satisfy the client’s need for competence and encourage the personal associations required for the endowment effect.

For more great ideas on how to incorporate your client into the design process, check out this article by Braingineers.

Don’t fall victim yourself

If the IKEA effect causes us to overvalue things that we spend time and effort on, it’s important to check our own beliefs and opinions, anytime we’ve become invested in an idea or project.

- Create calendar reminders to survey your opinions for the IKEA effect.

- Beware of sunken costs: the fallacy that says it’s better to double down on a failing project than to start afresh because you’ve already heavily invested.

Summary

What’s the IKEA effect?

The IKEA effect says that a person is likely to overvalue the things they make themselves, simply because they were involved in their production.

Even if somebody doesn’t enjoy working on a project or product, and doesn’t receive additional value for their efforts, the IKEA effect can still apply.

The IKEA effect may arise from three common cognitive biases: the need for competence, which says that we like to exert control over the things around us; effort justification, which says that we like to feel our efforts are worthwhile, and the endowment effect, which says that we prefer things that we feel connected to.

How to avoid the IKEA effect as a consumer?

We’re all vulnerable to the IKEA effect, even if we don’t consider ourselves to be hands-on or DIY fans. To avoid it, you’ll need to find ways to break out of your own perspective, which may have become distorted thanks to your invested labor.

Strategies for avoiding the IKEA effect involve shopping with a friend to get a second opinion or seeking feedback on your work from people who aren’t involved in the project.

How to use the IKEA effect in business?

Companies who make consumers part of the production process use the IKEA effect to convince us that their higher prices are reasonable.

Being able to customize a shirt or pair of shoes, tweak a coffee order, make meals from semi-prepared kits, or assemble our own furniture can all trigger the IKEA effect.

In a digital marketplace, where consumers are increasingly co-creators of value, companies are finding subtler ways to build the IKEA effect into product design.